Finally, the test-positivity rate has become much more reliable nationwide over the past few weeks. As recently as the end of March, not all states reported every negative test result from commercial laboratories. Nearly every state now publishes those numbers.

While our numbers still probably do not capture every coronavirus test in the U.S., outside evidence now suggests our data is fairly complete. When the White House Coronavirus Task Force has reported the number of tests completed nationwide, its numbers have broadly matched the COVID Tracking Project’s. In addition, the largest commercial test processors, Quest and LabCorp, have released top-line statistics that align with ours at the COVID Tracking Project.

The high positivity rate also suggests that new cases in the U.S. have plateaued only because the country has hit a ceiling in its testing capacity. Looking solely at positives, the U.S. is steaming toward 650,000 confirmed cases, but the number of new cases per day appears to be plateauing or even declining.

There are several ways to interpret this development. It might suggest, for instance, that the more than 3.2 million tests completed in the U.S. over the last two months have finally captured a good chunk of the people who are actually infected. While it’s clear that the country is not capturing every case, this decline in new positive cases might suggest the country has started to get the virus’s spread under control.

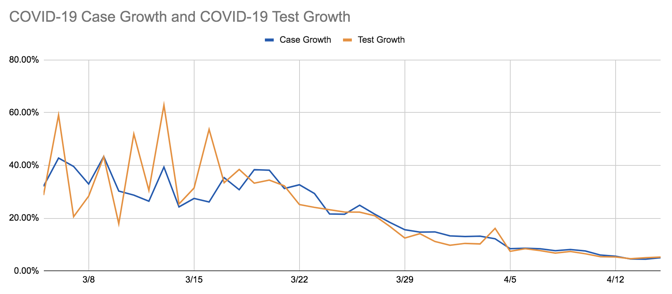

But there is another way to interpret the decline in new cases: The growth in the number of new tests completed per day has also plateaued. Since April 1, the country has tested roughly 145,000 people every day with no steady upward trajectory. The growth in the number of new cases per day, and the growth in the number of new tests per day, are very tightly correlated.

This tight correlation suggests that if the United States were testing more people, we would probably still be seeing an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases. And combined with the high test-positivity rate, it suggests that the reservoir of unknown, uncounted cases of COVID-19 across the country is still very large.

Each of those uncounted cases is a small tragedy and a microcosm of all the ways the U.S. testing infrastructure is still failing. When Sarah Pavis, a 36-year-old engineer in New York, woke up on Tuesday, she was out of breath and her heart was racing. An hour of deep breathing failed to calm her pulse. When her extremities started tingling, she called 911. It was her ninth day of COVID-19 symptoms.

New York City’s positivity rate is an astonishing 55 percent. More than 111,000 of the city’s residents have lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19, but Pavis is not among them. When the ambulance arrived at Pavis’s apartment, an EMS worker took her vitals, then explained there was little he could do to help. The city’s hospitals only admitted people with a blood-oxygen level of 94 percent or lower, he said. Pavis’s blood-oxygen reading was 96 percent. That two percent difference meant that her illness was not serious enough to merit hospitalization, not serious enough to be tested, not serious enough to be counted.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

/media/None/image/original.png)