Sister Souljah’s first novel has sold more than 1 million copies since it was published, a statistic that doesn’t even account for the many young readers who passed it around in classrooms, buses, and locker rooms like contraband. “The Coldest Winter Ever is one of those books we all read in middle school, or high school, when we were entirely too young,” the book blogger Ms. Malcolm Hughes put it in a recent video review.

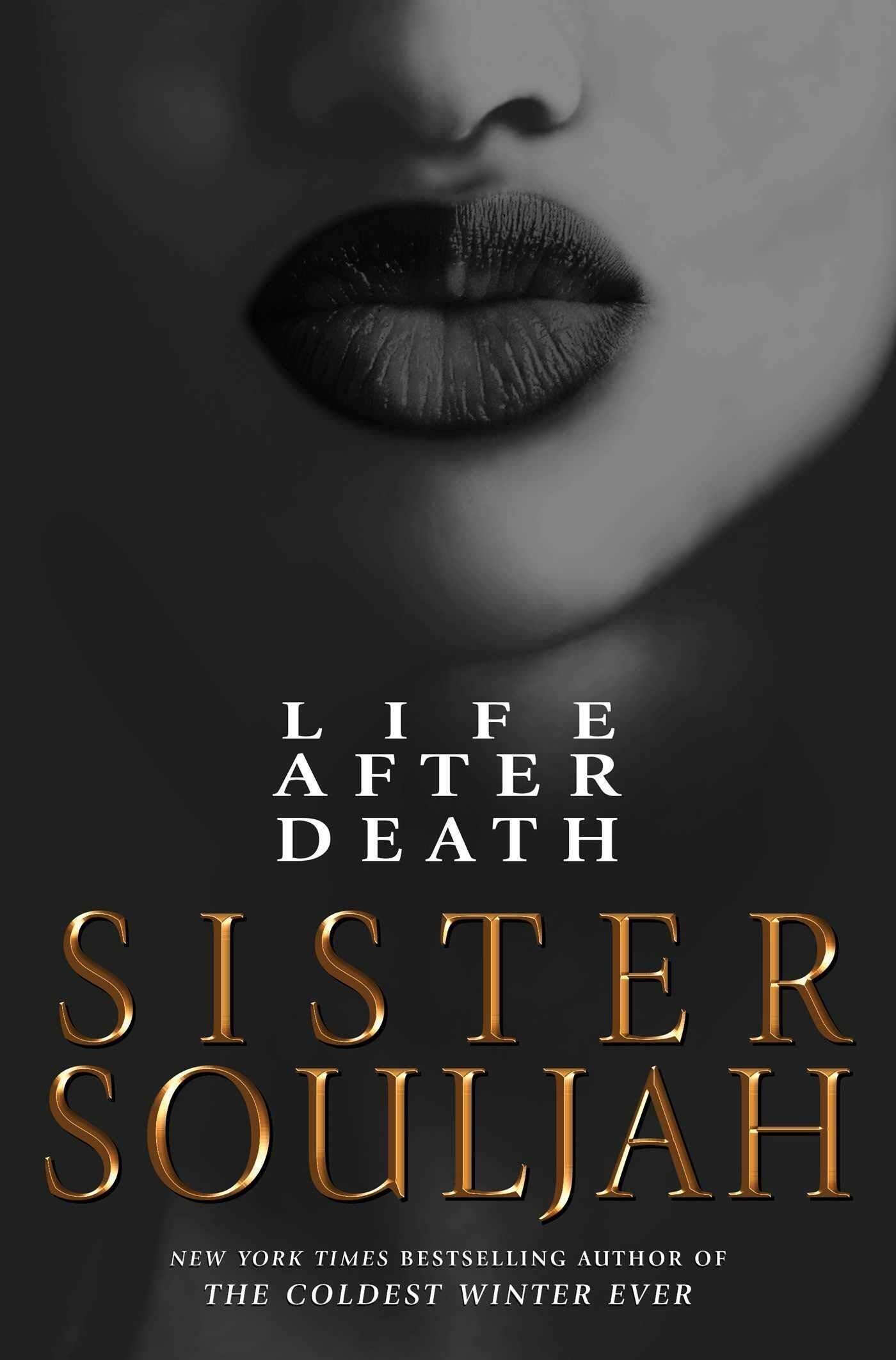

“I don’t think it’s right for any author to decide [their own] work is classic,” Sister Souljah told me in an interview last week. “But when … the high schools use it; and the junior high schools are not authorized, but they use it anyway; and everybody’s mother read it; and the grandmother read it—that is the people saying, No, this is a classic novel.” The Coldest Winter Ever is often credited with popularizing “street lit,” sometimes referred to as “urban fiction.” Within a decade of the book’s release, the genre made up the most popular paperbacks at Black-owned bookstores around the United States. And now Life After Death presents an opportunity to more thoroughly consider literature of its kind—for those of us who first became acquainted with Winter as teens, and for a publishing industry that still doesn’t quite understand characters like her.

Street lit is a deceptively simple name for a rich, metatextual art form. Early works, including Omar Tyree’s Flyy Girl, featured young female protagonists getting caught up in the excesses of 1980s hip-hop culture, gang life, and drug usage. But the genre can include less nihilistic fare too. Young-adult fiction such as Angie Thomas’s 2017 novel, The Hate U Give, which explores the effects of gun violence and police brutality through the story of a teen girl, is a natural entrant to the category.

Read: ‘The Hate U Give’ enters the ranks of great YA novels

In the introduction to a 2013 anthology about street lit, the editor, Keenan Norris, connected the genre to a long history of literature and journalism chronicling the beauty and pitfalls of city life. He described the genre as “a body of American literature produced by post-1980s Black and Latino writers and deriving its formal structure, narrative technique, and themes from the determinist and naturalist fiction of past epochs in African American and American literature.” Norris drew parallels between street lit and early-20th-century noir novels, noting that authors such as Chester Himes brought the “detective-gumshoe narrative devices” and moral ambiguity of those white noir writers’ books to fiction about Harlem.

As Norris also points out, street lit is “undeniably tied to hip-hop in terms of its origins, raw content, and up-by-the-bootstraps entrepreneurship in the production and distribution stages.” Indeed, Life After Death takes its title from the posthumous second album of another Brooklyn juggernaut, the Notorious B.I.G., and does more than just gesture at his influence. In the novel, after hearing one of the late artist’s singles playing, Winter muses on rap’s power: “Nineties rappers and hip-hop music ruled the airwaves, reflected our culture, and moved our streets,” she explains. “It was dominant, not only in Brooklyn, but in all hoods in America and around the world.”

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community