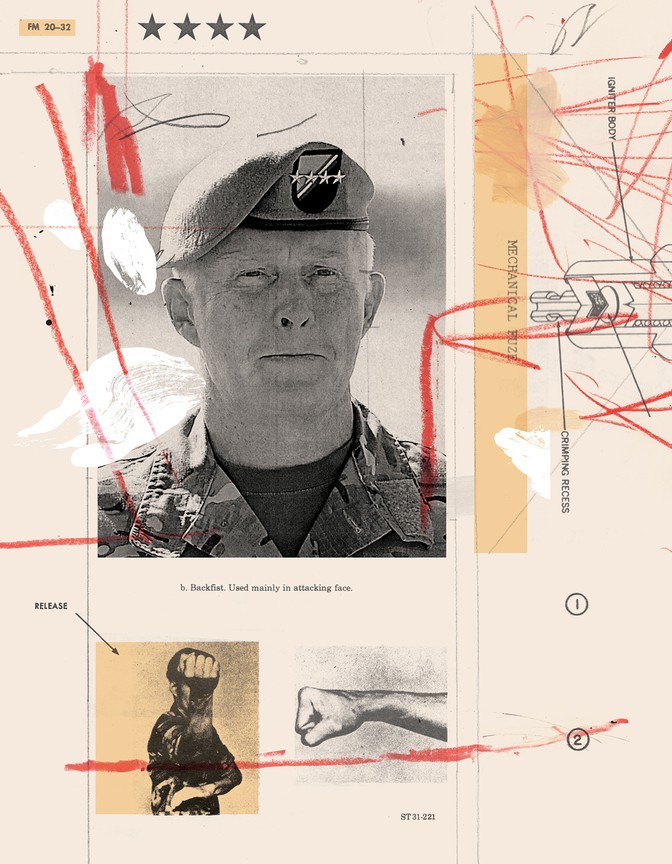

Illustrations by Mike McQuade

Image above, clockwise from top left: A U.S. Army Special Forces sniper, 1991; the aftermath of Operation Eagle Claw, the failed U.S. rescue operation in Iran, 1980; a marine during the invasion of Grenada, 1983; Captain Vernon Gillespie Jr. in Vietnam, 1964; soldiers on patrol at Camp Victory, in Somalia, 10 days after 18 Americans were killed during the Delta-led Battle of Mogadishu, 1993.*

This article was published online on March 12, 2021.

Within the span of a few decades, the United States has utterly transformed its military, or at least the military that is actively fighting. This has taken place with little fanfare and little public scrutiny. But without any conscious plan, I have seen some of the evolution firsthand. One of my early books, Black Hawk Down, was about a disastrous U.S. Special Ops mission in Somalia. Another, Guests of the Ayatollah, about the Iran hostage crisis, detailed an abortive but pivotal Special Ops rescue mission. U.S. Special Operators were involved in the successful hunt for the drug lord Pablo Escobar, the subject of Killing Pablo, and they conducted the raid that ended the career of Osama bin Laden, the subject of The Finish. By seeking out dramatic military missions, I have chronicled the movement of Special Ops from the wings to center stage.

Big ships, strategic bombers, nuclear submarines, flaring missiles, mass armies—these still represent the conventional imagery of American power, and they absorb about 98 percent of the Pentagon’s budget. Special Ops forces, in contrast, are astonishingly small. And yet they are now responsible for much of the military’s on-the-ground engagement in real or potential trouble spots around the world. Special Ops is lodged today under the Special Operations Command, or SOCOM, a “combatant command” that reports directly to the secretary of defense. It has acquired its central role despite initially stiff resistance from the conventional military branches, and without most of us even noticing.

It happened out of necessity. We now live in an open-ended world of “competition short of conflict,” to use a phrase from military doctrine. “There’s the continuum of absolute peace, which has never existed on the planet, up to toe-to-toe full-scale warfare,” General Raymond A. “Tony” Thomas, a former head of SOCOM, told me last year. “Then there’s that difficult in-between space.”

SOCOM, whose genealogy can be traced to a small hostage-rescue team in 1979, has grown to fully inhabit the in-between space. Made up of elite soldiers pulled from each of the main military branches—Navy SEALs, the Army’s Delta Force and Green Berets, Air Force Combat Controllers, Marine Raiders—it is active in more than 80 countries and has swelled to a force of 75,000, including civilian contractors. It conducts raids like the one in Syria in 2019 that killed the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and carries out drone strikes like the one in Iraq in 2020 that killed Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani. It works to locate hidden nuclear-missile sites in North Korea.

Using conventional forces is like wielding a sledgehammer. Special Ops forces are more like a Swiss Army knife. Over the years, the U.S. has found out just how versatile that knife can be; the flexibility and competence of Special Ops have proved invaluable. At the same time, the insularity and elitism of these units have bred a culture with elements that some of their own leaders, to their credit, have described as troubling, and that have, in certain instances, evidenced contempt for the traditional values of America’s armed forces. Much of SOCOM’s action takes place in secret. Most Americans are unaware that it has been active in a country until the announcement that its forces are being withdrawn. Or until something goes wrong—as in Niger in 2017, when four Special Ops soldiers were killed in an ambush.

Notably, its continued growth has been spurred by both success and failure. And perhaps because Special Ops is such a flexible tool, that growth has enabled the U.S. to multiply the way it uses force abroad without much consideration of overarching strategy. The advent of nuclear weapons, in the 1940s, presented leaders with urgent ethical and strategic imperatives. Defining the purpose of such weapons automatically demanded fresh thinking about the bedrock values of a democracy, the nature of multilateral alliances, the morality of warfare, and the scope of U.S. ambitions in the world. Because of its sub-rosa nature, Special Ops has not compelled the same kind of reckoning—and, in fact, may foster the illusion that a strategic framework is not necessary. It’s good to have a Swiss Army knife. And yet even a versatile knife can do only so much.

How did Special Ops come to occupy such a central role in American military operations—and even foreign policy?

The history of its rise is telling. In a defense establishment where each branch already sells itself as one of a kind—“The few. The proud”—there has been long-standing institutional distaste for a separate elite force, one that siphons off experience and talent and that is first in line for difficult missions. President John F. Kennedy bucked this convention when he stood up the Green Berets. It was a bright idea that burned out in Vietnam, where an initial commitment of Green Beret advisers—who did more than advise—escalated into a full-blown war, with more than 500,000 American troops deployed at its peak. The Green Berets survived as an elite unit, but many ambitious Army officers considered a berth in Special Forces a career-killer.

Then came the Iran hostage crisis, in November 1979. Two days after Iranian students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran, America’s top brass convened in the “Tank,” a subterranean conference room at the Pentagon, to consider how the military might respond if President Jimmy Carter ordered it to act.

Something called the Delta Force already existed on paper. It was the brainchild of Colonel Charlie Beckwith, a profane, hard-drinking, stubbornly tenacious Army officer who had served briefly with the British Special Air Service in Malaya. He had agitated so long to create a similar multipurpose commando unit within the U.S. military that he had alienated many up the chain, which helped explain why he was still a colonel when he retired. But in the mid-1970s, two spectacular rescue missions captured the headlines. A special Israeli unit stormed a hijacked airliner on the tarmac in Entebbe, Uganda, in 1976, rescuing more than 100 passengers. A year later, a special German unit did much the same in Mogadishu, Somalia. Beckwith’s stock abruptly rose.

When the Tehran embassy was seized, Delta Force had yet to undertake a mission, and the challenge posed was beyond any imagined for it. Rescuing scores of American hostages from a city of hostile millions who gathered regularly to chant “Death to America,” situated hundreds of miles from any potential staging area, was nothing like storming a parked airliner. But Carter wanted a military option.

“Obviously, we don’t want to do this,” said Major Lewis “Bucky” Burruss, Beckwith’s operations officer, as he briefed the brass in the Tank. The “if we must” plan he outlined was a bold and daring Rube Goldberg scenario. The bottom line was plain: We’re not ready.

Months later, they had to be; Carter was desperate. A new plan had been drawn up, only marginally more plausible. Choppers would deliver the Delta team to Tehran and then would pluck the team and the rescued hostages from a stadium near the embassy. They would all be flown to an airfield secured by a company of Rangers. Eagle Claw, as the mission was called, never cleared the first hurdle—getting to Tehran. The only helicopters large enough for the job couldn’t be refueled in-flight, so the choppers had to perform a complex nighttime rendezvous in the Iranian desert with tanker aircraft. An accident at the landing site ignited a fireball that killed eight servicemen. The mission remains one of the most humiliating failures in American military annals—a failure that became the impetus for expanding Special Ops.

In the aftermath of Eagle Claw, an investigation known as the Holloway Commission found the Pentagon woefully unprepared for daring, joint, pinpoint missions. It revealed a crippling lack of interservice and intergovernmental cooperation. Mission planners had had to plead to obtain blueprints of the embassy compound in Tehran. The Navy pilots flying the helicopters across the desert had not even conducted the practice runs the planners had requested.

As a remedy, the Holloway Commission recommended the creation of a Joint Special Operations Command—JSOC, as it would be known. The service branches hated the idea. Admiral James Stavridis, a former U.S. supreme allied commander in Europe and a man who spent his entire career in the conventional ranks, told me, “The Navy didn’t want to give up the SEALs, and the Army didn’t want to give up the Ranger battalions, and the Marine Corps wouldn’t even talk about it. The services fought it and fought it and fought it, at every level.”

Once created, JSOC was treated like a poor stepchild. In the end, a staff of 70 was dispatched to Fort Bragg to handle administrative chores. The group was given Delta Force, a SEAL team, and a rotating Ranger battalion for specific missions. A Special Ops helicopter unit was created. But JSOC depended on haphazard funding and relied on a grudging chain of command for missions.

That is how things stood in October 1983, when the U.S. invaded Grenada, a tiny island in the Caribbean. Its Cuba-aligned Communist government had collapsed, and its leader, Maurice Bishop, had been murdered. Saying he feared for the safety of 600 American medical students at the island’s St. George’s University, President Ronald Reagan had ordered the military to seize control of Grenada and bring the students home. Rescuing hostages being its prime focus, JSOC was a key player in the invasion, which was over fast. It was celebrated as a rousing success by the Reagan White House. But within the military, it was seen as an embarrassment.

General Thomas, now 62, was then a lieutenant who went in with the first wave. He had been a West Point cadet when the disaster in Iran had unfolded, and had no idea then how important that episode would prove to be for the military or for himself. But in fact he would be present for nearly every major U.S. military action of the next four decades.

The Grenada invasion, he said, was “a clown show.” JSOC had to rely on tourist maps for the most part, because military topographic maps were not available. Four SEALs drowned on a preinvasion reconnaissance mission. Cuban and Grenadian military personnel were known to be on the island, but no one knew exactly where or how many, or what kind of arms they had. Teams meant to be working together were unable to communicate because radio frequencies had not been coordinated. “We were lucky we were not up against the A team,” Thomas acknowledged.

Thomas’s platoon was part of an assault on the Calivigny barracks, where several hundred Cuban and Grenadian forces had reportedly retreated for a last stand. The attackers were crammed into four Black Hawks, as many as 15 Rangers in each helicopter—“I mean, just ridiculous loads,” Thomas recalled.

“We came skimming in over the ocean and had three out of the four helicopters crash,” Thomas said. Three more people died. No Cubans or Grenadians were at the barracks.

Major General Richard Scholtes, who had been the JSOC commander at the time of the operation, testified about these and other failures in a closed session of a Senate Armed Services subcommittee in August 1986. Senator Sam Nunn called the testimony “profoundly disturbing, to say the least.” And then he did something about it.

The disaster in Iran had led to JSOC. The mistakes in Grenada led to SOCOM. Thanks to an amendment sponsored by Nunn and Senator William Cohen, Special Ops got its own management and its own budget. Its annual budget today is about $13 billion, which is a sacrosanct 2 percent of all military outlays (and roughly what it costs to build an aircraft carrier). The Nunn-Cohen amendment also gave SOCOM clout. From now on, Special Ops would be headed by a four-star general or admiral, and its mission began to expand.

In 1987, Stavridis was a lieutenant commander on a cruiser stationed in the Persian Gulf as part of Operation Earnest Will, the largest naval-convoy mission since World War II. It was guarding Kuwaiti oil tankers, which were a lifeline for Saddam Hussein, who was then locked in a seven-year war with Iran—and being supported by the United States, his future enemy. The tankers were being preyed upon by Iranian forces. Special Ops teams used American ships as platforms to disrupt and counter Iranian attacks. Stavridis was impressed.

“It was the first time that we really started to see them in the field,” he recalled. The Kuwaiti ships had to be boarded and protected, which was not the kind of work the regular Navy did. “We, the Navy—Big Navy—hadn’t boarded a ship in a century,” Stavridis said. “These guys were trained to do that … as opposed to me trying to grab a bunch of boatswain’s mates and hand them a .45 and say, ‘Follow me!’ ”

Special Ops was the star of the 1989 invasion of Panama, an operation that went as smoothly as Grenada had gone badly. A Delta team located the dictator Manuel Noriega, and helped capture and bring him to the United States for prosecution as a drug trafficker and money launderer. Thomas was then a Ranger company commander. He called Panama JSOC’s “graduation event.” Leaders began to find new uses for Special Ops.

When Saddam invaded Kuwait, in 1990, President George H. W. Bush gathered an allied coalition to drive the Iraqis out. That effort, Desert Storm, would be a throwback to conventional warfare—a clash of big armies. But an opportunity for Special Ops quickly arose. In a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, the chairman, handed a report to General Wayne Downing, a former Ranger and then JSOC’s commander. Powell said, “This just in from the Israelis.” Iraq had begun firing Scud missiles at Israel from mobile launchers in the vast western-Iraqi desert. The Israelis were preparing an effort to find and destroy them, something Powell wanted to forestall. If the Israelis entered the war, it would offend Arab states and possibly cripple the coalition.

“Can you do that?” Powell asked Downing. Could he take out the Scuds?

Within days, JSOC teams were camped in remote desert observation posts, launching attacks on Iraqi missile columns from the air or swooping in across the sand in six-wheeled combat vehicles, looking like the pirate gangs of Mad Max. Questions would be raised later about whether these attacks were taking out real missile launchers or decoys fielded by Saddam, but there’s no doubt that the results achieved were fast and dramatic, and kept Israel off the battlefield.

The results were also on film. “We lucked out and came right on a Scud launcher two or three days after we started,” Thomas recalled. The assault was filmed from a helicopter, which flew lower and slower than the jets that provided most of the footage viewed at headquarters. JSOC’s imagery was as intimate and vivid as a video game’s. After the first Scud launcher was destroyed, Downing played the tape at a briefing for General Norman Schwarzkopf, the commander of allied forces, who was struck by the immediacy and detail. “Norm said, ‘Whoa, whoa, is this a training tape from back at Bragg?’ ” Thomas recounted. “And Downing said, ‘No, this was up by al-Qa’im last night in northern Iraq.’ ” Search-and-destroy became another SOCOM specialty.

Experienced SOCOM soldiers were early adopters of new technology, often buying equipment off the shelf that was not available through normal supply lines. As in most other fields, modern telecoms would transform war-fighting.

In December 1998, Thomas had what he called a “sensor-to-shooter epiphany” in the closed back of a truck near Vrsani, a village in northeastern Bosnia. Then a lieutenant colonel, he was in command of a JSOC Delta squadron. The mission was manhunting. Thomas and the squadron had been tracking Radislav Krstić, a one-legged Serbian commander in the Yugoslav wars who had been indicted a month prior by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, in The Hague.

Thomas’s unit had been watching Krstić for days. Surveillance drones were still in the future, but Thomas did have a helicopter with a high-speed camera. It fed a live picture to a Sony television that Thomas held on his lap. His truck was hidden in a thicket about 200 yards from a road he knew Krstić would use. German special forces had provided a snare—a net made of sturdy elastic that could capture even a speeding vehicle.

Bottom: Images from “Hand-to-Hand Fighting,” a U.S. Army Special Forces manual. (Mandel Ngan / AFP / Getty; U.S. Army Institute for Military Assistance)

Gunplay was a possibility, so Thomas had a list of strict no-go scenarios, among them the presence of local police, Russian troops, or children. As Krstić’s vehicle neared, first a Russian convoy approached, then a local military-police vehicle. Both passed by. Finally a school bus rolled into the picture. The effort seemed snakebit. At last, on the screen, Thomas watched the school bus clear the zone, with only seconds to spare. “Execute!” he ordered. Krstić’s vehicle was caught in the net, and he was taken without incident.

Thomas would be teased about the episode: an entire Delta squad to capture a one-legged Serbian? What stuck with him was how much more useful the screen had been than his own two eyes. Without the overhead view covering the whole stretch of road, he would have aborted the mission. It occurred to him: This is where we are going in the future.

Live video feeds were just the beginning. When Stanley McChrystal took over JSOC, in 2003, the U.S. invasion of Iraq was eight months old. Special Ops teams were still hunting Saddam and other “high-value targets” when a new enemy arose: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a jihadist known as “The Sheikh of the Slaughterers.” His followers were setting off bombs in crowded places, attacking American soldiers, and kidnapping “infidels” and beheading them in horrific videos posted online.

McChrystal was known as a relentless striver. Gaunt, hollow-eyed, and intense, he was famous for his ascetic discipline. He turned his task force into the most efficient hunter-killer force in the world, and a model for the entire command. McChrystal is not Sun Tzu. But in sizing up his adversary and responding creatively, he remade JSOC, and ultimately SOCOM itself. He recognized that the ability to digitize information—audio files, video files, maps, texts, emails, phone calls, documents—could steer him rapidly to targets.

Like most innovations, McChrystal’s was resisted, including by SOCOM itself. He wanted to expand and alter his mission, adding an array of expertise—in some cases, requiring civilian contractors—that had nothing to do with traditional soldiering. He explained the situation to me in a way that both made his position understandable and underlined the institutional imperatives that push in one direction only. “Inside my command, there were a bunch of people saying, ‘We need to pull back to the States and wait until there’s a hostage rescue or something like that, and we’ll do our specialized mission,’ ” McChrystal said. “And I told them, ‘Hey, if we’re not here doing a significant part of this, we’re not going to be able to claim our elite status and be first in line for resources and priority.’ ” There was also resistance from agencies whose support he needed, notably the CIA, which balked at moving interrogators, analysts, software engineers, and imagery experts out from under their direct control. But McChrystal got what he wanted.

His refurbished, tech-assisted team found, fixed, and finished Zarqawi himself with an air strike at one of his hideouts north of Baghdad in June 2006. By that time, his terror network had been decimated. His death was important in the moment, but it also illustrated the limits of even a highly skillful application of force. The insurgency persisted and ultimately morphed into ISIS. McChrystal’s remarkably successful efforts were less of a factor in reversing the war’s direction than General David Petraeus’s “surge,” in 2007. What McChrystal had done was give SOCOM an amazingly potent new tool.

And people noticed. Money, McChrystal recalled, was available for whatever he needed. The very definition of JSOC changed, again. It was no longer just elite “operators” or “shooters” descending from silent choppers; it had become what a business-school case study might call a fully integrated intelligence-and-assault network. But as McChrystal acknowledged, there would always be skeptics, within SOCOM and elsewhere, who believed that “we ought to go back to being a tiny group of people.” And, as he also acknowledged, a revolution in Special Ops tactics isn’t the same thing as strategic wisdom, or success.

Hostage rescue, manhunting, search-and-destroy missions—these had become the U.S. military’s active pursuits worldwide. Other events secured SOCOM’s status. The most dramatic was the killing of Osama bin Laden, in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011. After the CIA traced his location, a SEAL team penetrated Pakistan’s air defenses and hit his compound. Thomas was second in command on that mission, under JSOC’s Admiral William McRaven, who became SOCOM commander later that year. Despite his background leading shooters, McRaven promoted the softer side of the command, long a major part of its portfolio—the Green Beret teams of people who were familiar with local languages and cultures, knew how to build ties with communities, and had the diplomatic skills to serve as advisers rather than call all the shots.

That approach found a receptive audience in President Barack Obama, who was trying to crush emerging terror threats while at the same time lower American troop levels overseas. SOCOM’s small units would steer the battle against Islamist networks in Africa and Asia, working primarily through local armed forces. Its intelligence network and aerial assets would give Kurdish, Iraqi, and Syrian fighters an overwhelming advantage against ISIS. Utilizing SOCOM, the U.S. was still in the fight, just not openly in the lead, and no longer carrying the full load. This opened Obama to political attacks for “leading from behind,” which revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of the change under way. Happy to keep American forces below the radar, Obama was eager to act when the occasion was ripe. Thomas described Obama as “a junkyard dog” when it came to national security.

SOCOM was so active during Obama’s tenure—in addition to the large deployments in the Middle East, there were smaller units in Niger, Chad, Mali, South Korea, the Philippines, Colombia, El Salvador, Peru, and dozens of other countries—that the Pentagon was leery of opening major new fronts. When al-Shabaab, the militant Islamist group in Somalia, showed signs of mounting strength, there was some worry that Obama might want to go in heavy. Thomas was in the room when Pentagon commanders laid out the options, expecting the president to expand the mission. At the conclusion of the briefing, he recalled, Obama made two points: “One, ‘We don’t know enough about the problem.’ And two, ‘Maybe the best thing we can do is mow the grass’ ”—meaning, manage the problem around its edges, quietly. SOCOM gave him the option of mowing the grass, at least for a time.

Special Ops forces are popular for two reasons, McChrystal explained: “One, because they’re sexy, and two, because they are viewed as a way to do things on the cheap, meaning you could send 10 brave people in to do a job instead of 100,000 soldiers, which has political costs and casualties.” The reality, he went on, is that the nonsexy parts of Special Ops are the ones that may have more lasting impact. Killing or capturing a murderous foe appeals to a sense of justice and provides momentary satisfaction, but eliminating a terrorist leader is not victory. It is, in Obama’s words, just mowing the grass.

As Obama explained when I spoke with him after the bin Laden mission: “Ultimately, none of this stuff works if we’re not partnering effectively with other countries, if we’re not engaging in smart diplomacy, if we’re not trying to change our image in the Muslim world to reduce recruits” to extremism. The targeting engine itself, he said, “is not an end-all, be-all. I’m sure glad we have it, though.”

There is a risk in being admired by those in charge. During Thomas’s tenure as SOCOM commander, from 2016 to 2019, the scope of his responsibility grew at a pace he calls “frantic.” New tasks were given to his already swollen organization, grafted on like afterthoughts, even as Obama’s successor as president made several dramatic troop reductions or withdrawals, notably in Syria and Afghanistan. Donald Trump’s words and policies were unpredictable, but SOCOM’s mission continued to enlarge.

Fighting violent extremism remained an active priority—combatting groups such as the Taliban, ISIS, al-Qaeda, and al-Shabaab. SOCOM was also tasked with developing contingencies for conflict with Iran and North Korea. Thomas was already fielding units in virtually every European country bordering Russia and developing plans to deter China. In 2017, responsibility for policing weapons of mass destruction worldwide was handed from U.S. Strategic Command to SOCOM, which was given information operations at about the same time. To compete on the computer-assisted modern battlefield, SOCOM has taken the lead in employing artificial intelligence. And then there are all those “open,” or unclassified, missions around the world—training local militaries, and building relationships and intelligence.

Thomas admits that he fought a losing battle to keep his command from becoming bigger and more bureaucratic. Despite his requests for guidance from Secretary of Defense James Mattis—for more carefully sorted priorities—the new missions just kept coming. He never did get direction from the top. And his own input was not avidly sought. “We weren’t even involved in the National Defense Strategy discussions,” Thomas told me. He recalled asking General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, “Hey, why am I not in the Tank?” Dunford replied, “Tony, you’re not a real service. You’re a ‘service-like entity.’ ”

Thomas believes that his former command ought to be designated an official branch of the military, and so does James Stavridis. William McRaven disagrees, arguing that SOCOM’s strength is the “joint” flavor of it: “You get diversity of thought, you get diversity of background, and there’s nothing better to creating a good decision than having diversity.” General Joseph Votel, who followed McRaven as SOCOM commander, is ambivalent about formal status, but believes that the SOCOM commander ought to be a member of the Joint Chiefs.

Clearly the key player in U.S. military operations worldwide should have a seat at the planning table. Barring the outbreak of a catastrophic war between major powers, SOCOM will likely remain a primary way America projects force, one that is well suited to the global, varied, and collaborative nature of war in the 21st century. This itself prompts questions about whether America’s vast outlays for the traditional military services are being well spent, and whether they could be reduced. But SOCOM’s own growth should also make us wary. The power to order pinpoint strikes and killings, often cloaked in secrecy, enables a president to act with minimal public scrutiny, and can tempt a president to substitute a few small, dramatic exploits for a more sustained strategy. As SOCOM’s leaders recognize, one cannot defeat a culturally rooted movement, such as al-Shabaab, by occasionally bumping off its leaders. Moreover, once you start mowing the grass, where and when do you stop?

Even beyond all that, bigness may, in the long run, challenge SOCOM’s effectiveness. It has become a central actor in today’s military because of its rapid adaptability and because of the expertise and experience of its forces. As it grows ever larger, it risks losing more than just its elite status. It risks evolving into the very self-justifying, calcified bureaucracy that it was designed to supersede.

This is already happening. The early Delta Force’s administrative staff was skeletal. Today, SOCOM’s central command, at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida, is large and complex. “People often accuse the military of throwing money at problems,” Bucky Burruss, the former Delta Force officer, told me. “We don’t do that. We throw headquarters at problems. And another headquarters eventually becomes just another layer you have to get through.”

McChrystal saw it coming. He remembers attending a military conference in 2007. He ran into another predawn gym rat, a retired Navy SEAL, who lamented, “It’s just not like the old days, is it?”

“No,” McChrystal agreed. Then he asked, “What do you mean?”

“These guys just aren’t—” McChrystal thought he was about to say “heroes” but had stopped himself. “They’re not like we were.”

“What are you talking about?” McChrystal replied. “These guys are doing a hundred times more than we ever dreamed of doing, and doing it better.”

His friend seemed disappointed by the response, so McChrystal explained further: “It’s not just a few, you know, burly men anymore. Shit, this is a machine now. You and I don’t even know how to run it.”

* Lead image credit: Illustration by Mike McQuade; images from Leif Skoogfors; Rolls Press / Popperfoto; Corbis; Larry Burrows / Life Picture Collection; Joel Robine / AFP / Getty

This article appears in the April 2021 print edition with the headline “How Special Ops Became the Solution to Everything.”

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community