Johnson tried to side-step his loss of control by proroguing Parliament. His opponents challenged him in court and won, forcing Monday’s ceremonial reopening. The queen’s speech is traditionally followed by a vote. As things are going, Johnson looks likely to lose that vote, too. After expelling 21 Conservatives from his own caucus to punish them for prior rebellions, he can count on only 288 votes in the House of Commons, 32 short of a majority.

At any previous moment in British history, Johnson’s government would have fallen by now and an election been called. But Britain amended its law in 2011 to fix parliamentary terms at approximately five years, unless two-thirds of Parliament voted for an early election. The idea was to ensure stability. Instead, the fixed-term amendment has created a political ghostland: a government lacking democratic legitimacy, but also unable to put itself out of its own misery. (One of the votes Johnson lost was a vote for early elections.)

Andrew Cooper, the pollster and strategist to former prime minister David Cameron, offers one explanation as to why Britain cannot form a stable government.

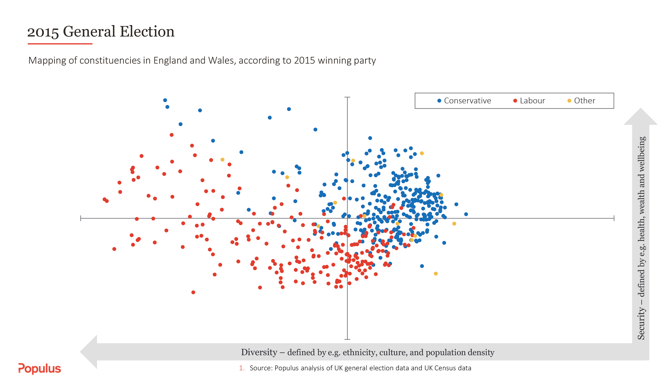

Twenty years ago, the safest Conservative seats in the country were mostly economically secure and mostly ethnically English. The safest Labour seats in the country were mostly economically distressed and ethnically diverse. The two parties would then battle for the votes of everybody else, but the clash between the economically secure English and the distressed and diverse provided the main battle front of British politics.

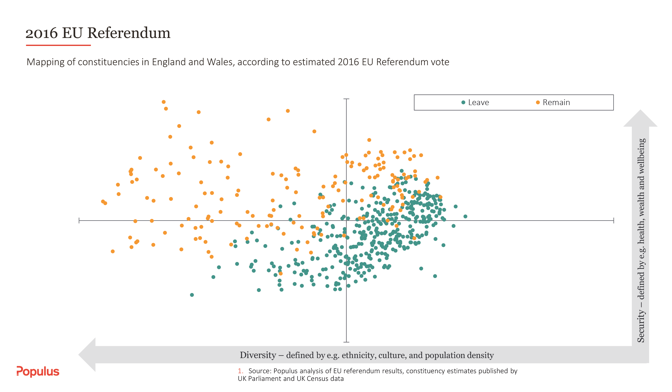

Over the past two decades, this map of politics has lost relevance. Only 9 percent of British people still strongly identify with a political party. Old partisan identities have faded before a sharp new bifurcation, Leave versus Remain. Almost 90 percent of British voters identify with these new ideological categories, 44 percent do so strongly. This new bifurcation has rotated the old political map. Leave is strongest where voters are distressed and ethnically English. Remain is strongest where voters are economically secure and diverse. The old parties are struggling to find their footing in the new heartlands.

Read: Why a ‘Brexit Election’ will make things worse

By committing to Leave, the Conservatives have acquired new supporters who want more government protection from the rigors of globalism—even as the party’s own internal justification for Brexit was to rip up EU regulations, shrink the British state, and reposition Britain as more global, not less. With the government determined to Leave, the opposition Labour Party should logically speak for Remain. But under the left-sectarian leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, Labour does not want the voters who would be attracted to a Remain message. This has left Labour with no coherent message at all on the single most important issue facing the country.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community