See: Photos of Tiananmen Square, then and now

In moving on to tackle the Cultural Revolution, he acknowledges that his firsthand experiences during those years did not prove to be much help. At the time, he hadn’t understood it well, and “missed the forest for the trees,” he writes. Five years after the upheaval ended, the Communist Party’s Central Committee adopted a 1981 resolution laying down the official line on the horrifying turmoil. It described the Cultural Revolution as occasioning “the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the state and the people” since the founding of the country. At the same time, it made clear that Mao himself—the inspiration without whom the Chinese Communist Party could not remain in power—was not to be tossed onto the rubbish heap of history. “It is true that he made gross mistakes during the Cultural Revolution,” the resolution continued, “but, if we judge his activities as a whole, his contributions to the Chinese revolution far outweigh his mistakes.” To exonerate Mao, much of the violence was blamed on his wife, Jiang Qing, and three other radicals, who came to be known as the Gang of Four.

In The World Turned Upside Down, Yang still dwells very much amid the trees, but he now brings vividness and immediacy to an account that concurs with the prevailing Western view of the forest: Mao, he argues, bears responsibility for the cascading power struggle that plunged China into chaos, an assessment supported by the work of, among other historians, Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, the authors of the 2006 classic Mao’s Last Revolution. Yang’s book has no heroes, only swarms of combatants engaged in a “repetitive process in which the different sides took turns enjoying the upper hand and losing power, being honored and imprisoned, and purging and being purged”—an inevitable cycle, he believes, in a totalitarian system. Yang, who retired from Xinhua in 2001, didn’t obtain as much archival material for this book, but he benefited from the recent work of other undaunted chroniclers, whom he credits for many chilling new details about how the violence in Beijing spread to the countryside.

The Cultural Revolution was Mao’s last attempt at creating the utopian socialist society he’d long envisioned, although he may have been motivated less by ideology than by political survival. Mao faced internal criticism for the catastrophe that was the Great Leap Forward. He was unnerved by what had happened in the Soviet Union when Nikita Khrushchev began denouncing Joseph Stalin’s brutality after his death in 1953. China’s aging despot (Mao turned 73 the year the revolution began) couldn’t help but wonder which of his designated successors would similarly betray his legacy.

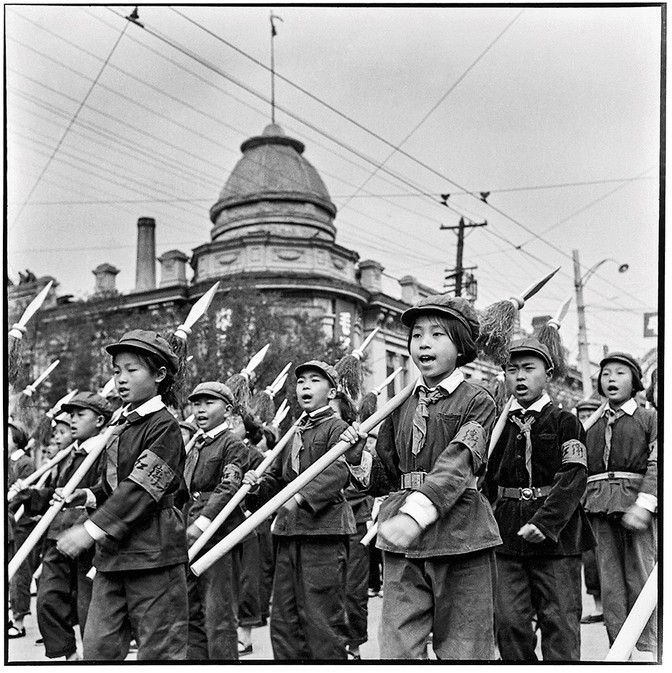

To purge suspected traitors from the upper echelons, Mao bypassed the Communist Party bureaucracy. He deputized as his warriors students as young as 14 years old, the Red Guards, with caps and baggy uniforms cinched around their skinny waists. In the summer of 1966, they were unleashed to root out counterrevolutionaries and reactionaries (“Sweep away the monsters and demons,” the People’s Daily exhorted), a mandate that amounted to a green light to torment real and imagined enemies. The Red Guards persecuted their teachers. They smashed antiques, burned books, and ransacked private homes. (Pianos and nylon stockings, Yang notes, were among the bourgeois items targeted.) Trying to rein in the overzealous youth, Mao ended up sending some 16 million teenagers and young adults out into rural areas to do hard labor. He also dispatched military units to defuse the expanding violence, but the Cultural Revolution had taken on a life of its own.

In Yang’s pages, Mao is a demented emperor, cackling madly at his own handiwork as rival militias—each claiming to be the faithful executors of Mao’s will, all largely pawns in the Beijing power struggle—slaughter one another. “With each surge of setbacks and struggles, ordinary people were churned and pummeled in abject misery,” Yang writes, “while Mao, at a far remove, boldly proclaimed, ‘Look, the world is turning upside down!’ ”

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community