Indirect questions yield a somewhat different story, however. A 2015 Healthline survey revealed that more than 18 percent of people say they are very stressed during the holidays, and another nearly 44 percent say they are somewhat stressed. Similarly, a 2006 survey by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, a polling firm, found that during the holidays, 61 percent of respondents reported feeling stress, 36 percent felt sad, and 26 percent felt lonely. For many, “holiday cheer” is conjured from a bottle: The American Addiction Center surveyed 1,000 Americans about their drinking consumption during the holidays and found that roughly 27 percent of men and 17 percent of women drank enough “to have difficulty recalling their celebration.”

Read: A tragic beginning to the holiday season

This is why I believe there may be a good amount of hidden unhappiness around the holidays, even in the merriest of years. And this is a year that will be especially trying. For some, it is a season marked by continued fear and loss from the pandemic. For many families (like mine), there are painful separations that cap months and months of already being apart.

More than usual, people can use some holiday-happiness assistance.

I’m no shy voter, so let me confess right here that while I don’t hate the holidays, I’ve never been a major fan, either. My father died on Thanksgiving Day. While that event occurred decades ago, it still marks the day for me. And Christmas? I am content to celebrate it as a religious observance, but the secular aspects feel socially coercive and commercially predatory. My feelings are complicated, to say the least.

Beyond individual tastes or personal experiences, social science has provided some explanations for why the holidays might be less than blissful. A lot of it comes down to social comparison, which is one of life’s most predictable joy killers.

In 2011, a team of psychologists writing in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that humans are remarkably bad at assessing the true emotions of others, including people close to them. In experiments, they found that people tend to systematically underestimate the negative emotions others feel, and overestimate positive emotions. They compare their own happiness levels to those they (often incorrectly) perceive in others, and this causes, in the authors’ words, “greater loneliness and rumination and lower life satisfaction.”

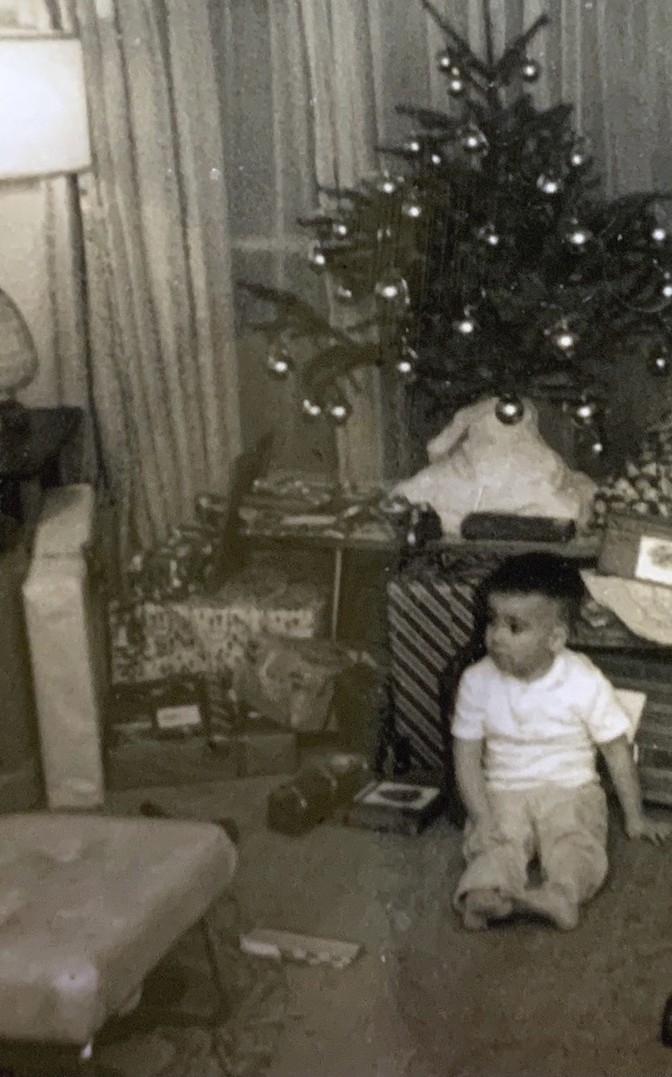

Social media makes this error easier than ever to commit, especially around the holidays. Spend time perusing a friend or relative’s Facebook page around Christmas, and you will see pictures of people having a wonderful time. But, of course, these messages and images are carefully curated. No one posts a photo of a blowout political argument at dinner, or mentions the crippling anxiety they get from the credit-card debt they racked up buying presents. We know this intellectually, but as the scholars show, we somehow can’t factor this into our evaluations of others’ true happiness.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community