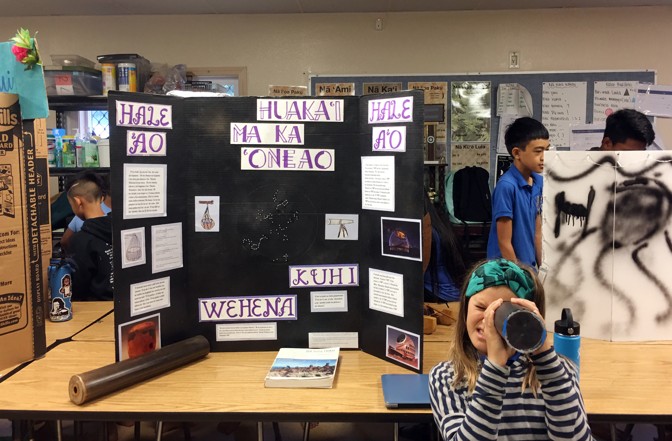

This approach, Kelling told me, has all kinds of benefits. For one, it reclaims customs that Western assimilation sought to phase out. Mo‘olelo, traditionally, were told aloud; repeating this process, for Kelling, creates a visceral appreciation for that history in students who may otherwise be detached from it, humanizing the stakes. “Language is the soul of the people,” Kelling said—it’s not just for communicating, but also for understanding and feeling and remembering.

Experiential-learning techniques such as these have been found to promote memory and motivation. Kelling focuses on students’ cultural identity, leveraging his personal experience of growing up in a school system that downplayed the Hawaiian language and failed to engage him in his education.

The reliance on storytelling bolsters his teaching, too. “We come to understand sorrow or love or joy or indecision in particularly rich ways through the characters and incidents we become familiar with in novels or plays,” wrote Kathy Carter, a University of Arizona education scholar who studies teaching and language, in a 1993 paper for Educational Researcher. “This richness and nuance cannot be expressed in definitions, statements of fact, or abstract propositions. It can only be demonstrated or evoked through story.” Studies also show that culture-based education can increase students’ self-confidence, self-esteem, and resiliency—skills that may have pronounced value for indigenous youth. Native Hawaiians are disproportionately poor: Roughly 14 percent of Hawaii residents who identify as Native Hawaiian live in poverty, according to 2017 data, compared with less than 10 percent for the state population as a whole. They also experience higher than average rates of teen pregnancy, substance abuse, and suicide.

Ultimately, it’s hard to compare the educational merits of Hawaiian-immersion schools with those of their traditional K–12 counterparts. Too many factors are at play. One of the big issues, several of the people whom I interviewed for this story told me, is the failure of conventional academic standards to acknowledge indigenous worldviews. But for Kelling and other immersion advocates, that doesn’t matter. In just a few decades, immersion schools have helped Native Hawaiians to reclaim their language.

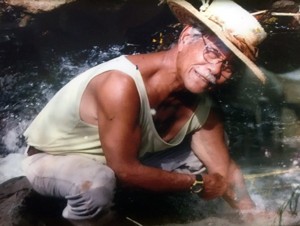

Kelling didn’t appreciate the language until relatively late in life. Raised in a working-class neighborhood near Pearl Harbor, Kelling liked “climbing trees and stuff” as a kid and was obsessed with surfing as a teen. He didn’t speak a lick of Hawaiian. Perhaps thanks to the constitutional ban, which was lifted just as Kelling was making his way through adolescence, he would’ve struggled to learn it even if he tried. After enrolling at the University of Hawai‘i, he eventually decided to major in Hawaiian. It was through this degree program that he started teaching at Pūnana Leo’s downtown Honolulu preschool. These early teaching experiences exposed Kelling firsthand to the consequences of linguistic and cultural erasure; he was overwhelmed with a sense of urgency.

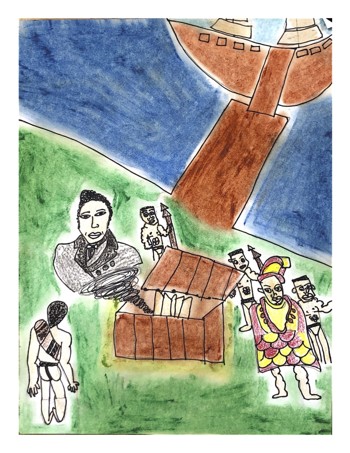

And it was largely through mo‘olelo that he came to this revelation. Mo‘o refers to the small green lizards found throughout the islands, but according to some analyses it also means “succession,” “trajectory”—an allusion to the lizard’s skeleton, the way the vertebrae connect piece by piece. ʻŌlelo means “language,” speech.” Mo‘olelo, then, is the succession of talk or language, and it’s how Native Hawaiians communicated and spread knowledge before the islands were infiltrated by the outsiders who would eventually destroy their kingdom.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community