The raw power of correspondence: Your weekly guide to the best in books

“Mr. Higginson,” an unpublished, reclusive 31-year-old poet wrote to an Atlantic contributor—a man she had never met—in 1862. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive? The mind is so near itself it cannot see distinctly, and I have none to ask.”

The letter, with its quaint phrases and handwriting that looked almost like bird tracks, was unsigned, and accompanied by a card nestled under a smaller envelope. The name on the card was Emily Dickinson. As Martha Ackmann recounts in These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, the letter set off a long-term correspondence—and when Dickinson and its recipient finally met eight years later, she spoke with all the confidence of a writer sharing a literary manifesto.

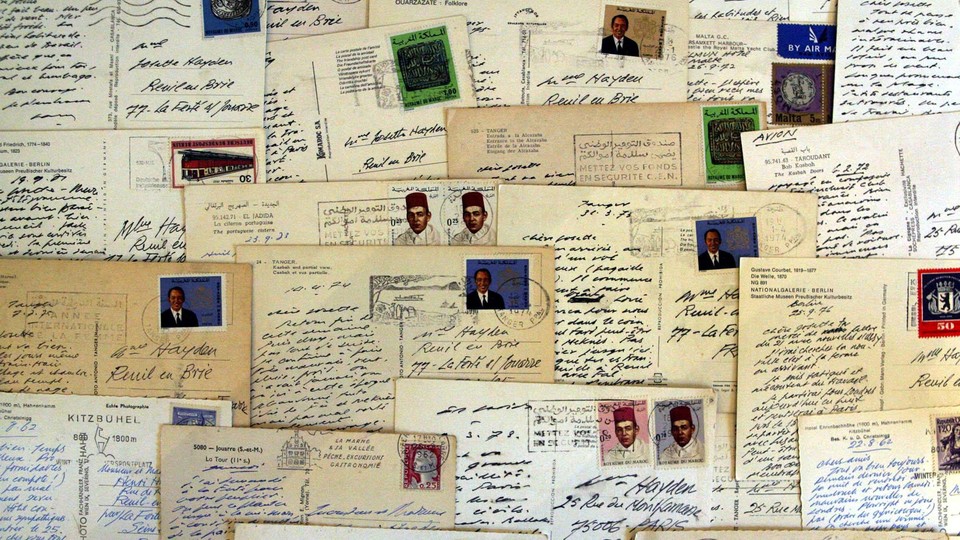

Literary letters can give us new insights into the development of authors we thought we already knew well, or can sometimes lead us to think about their work in a new way. The letters of Hunter S. Thompson show a man who is “hard, compulsive, vengeful, nastily funny, and distended with the grandiosity of true desperation,” writes my colleague James Parker—who still ultimately found in them a way to understand “the huge, throbbing interrogative that is America.” By their nature, many collections published posthumously are unpolished first drafts—albeit by talented writers. Yet correspondence can offer raw honesty and practical guidance in the face of existential crises such as aging, and is its own literary tradition. Black writers, in particular, have found essays in the form of open letters to be an effective vehicle for activism and sharing survival tactics with loved ones, as Emily Lordi notes in a review of Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times. There seems to be an inherent power to the medium—one that can’t be displaced by, and in fact will probably outlive, today’s group text.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

The author James Baldwin popularized the letter-essay as a personal-political form. (Associated Press)

The Intimate, Political Power of the Open Letter

“These works are addressed to family and friends … [and] detail the psychic effects of racial oppression, often including fear for the authors and their children. In different ways, these letters balance two aims: to enlighten the outside world and, perhaps more importantly, to share tactics of survival and resistance with kin and whoever else might need them.”

Universal History Archive / Mondadori Portfolio / Getty / The Atlantic

The Encounter That Revealed a Different Side of Emily Dickinson

“In her letters, Higginson had noticed, she no longer signed her name on a card slipped inside the envelope—a game played as much for effect as reticence. Largely gone, too, were the callow signatures of ‘Your Gnome’ and ‘Your Scholar.’ Now she signed her name with a single word: ‘Dickinson.’ That is who she had become.”

Paul Harris / Getty

Hunter S. Thompson’s Letters to His Enemies

“Thompson’s letters impart the lesson: Decades later, this is the same America—the America of the raised nightstick, the shuddering convention hall, the booming bike engine, the canceled credit card, and the impossible dream.”

Hulton Deutsch / Bettmann / AFP / Stringer / Getty / Library of Congress / The Atlantic

Finding Wisdom in the Letters of Aging Writers

“As 21st-century writers have transitioned from letter writing to email, a specific literary tradition seems to have come to its end, one that offered a slower, more meditative, and writerly microscope into all aspects of life, including the aging process … There is much practical and intellectual guidance to be gleaned from spending time with imaginative, highly articulate individuals as they face the existential realities of illness, declining productivity, the death of friends, guilt, and, finally, letting go of cherished activities and passions.”

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Mary Stachyra Lopez. The book she’s reading next is It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940–1980, edited by Dan Nadel.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community