It took some effort to decide which dreams were real and which were fake, but he usually chose which submissions to respond to based on what he found personally striking. For instance: “Celine was sitting in a place I do not know at all, but I had a feeling that I had known that place,” a Canadian woman named Pauline wrote in. “It was obvious to take a picture of her. And here is the whole strangeness of my dream. That woman didn’t look like Celine, but I felt it was her. When I was about to take a photo of her, I realized I had no plates in my camera.”

Toroptsov’s interpretation was characteristically crisp and polite. “What seemed to be the right place and the right time is actually an illusion,” he responded. “The lack of clarity in the dream might suggest a situation you find yourself in at the moment. The best strategy to advance when the road is not completely clear is to slow down and take one step at a time.” Toroptsov signed off as he usually did, with “Thanks for sharing your dream!”

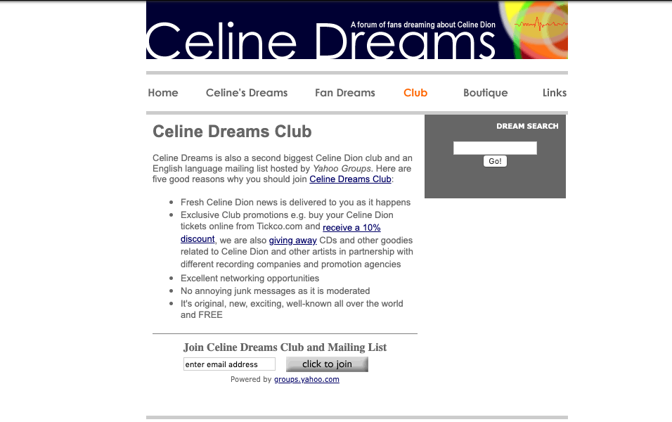

Celine Dreams became so popular that Dion’s team listed it on her official website (though Dion’s publicist declined to comment on whether the singer is personally aware of the site). Concert-ticket resellers paid Toroptsov an average of 100 euros a month each to link to them. He earned commissions on Amazon referral links in his site’s “boutique.” He became part of an ecosystem of high-profile Celine Dion fans—the type of mythological fandom figure that’s sometimes referred to as a “big name fan,” or BNF. Toroptsov was aware that a lot of people find Celine Dion tacky or over the top, but he didn’t care. Many of those people, he said, would still listen to “My Heart Will Go On” all the way through to the end if they were sitting somewhere alone.

Read: The purest fandom is telling celebrities they’re stupid

“I knew some people took me for an idiot,” he said. “Well, so what? For me, I believe that for something to exist on this scale within a popular culture, it cannot be a thing that doesn’t mean anything or doesn’t have any connection to the people of that time … It touches something, and there is some truth in this.”

Though the basic conceit of Celine Dreams sounds hallucinatory now, it was actually pretty common for fan sites to have dream sections at the time. Fans going online to talk about the subjects of their devotion were often also looking for some outside expertise on why their favorite stars loomed so large in their mind. It made sense to turn to dreams for some hints.

Celine Dreams was at its peak from 2003 to 2007. It was also just one in a sea of thousands—hundreds of thousands, maybe—of fan sites during the early aughts, all enabled by platforms like GeoCities, Angelfire, and Tripod. Supplemented by the community features of Yahoo Groups, fan-specific forums, and email listservs, these sites were a major factor in what made the early web seem so promising. For a few years, it looked like people might use the internet primarily to talk and teach about things they loved.

Yahoo Groups, a combination of listserv and forum features that launched in 2001, the same year as Celine Dreams, was one of the first tools that fans used to congregate en masse online. In 2010, Yahoo said it had more than 115 million users in 10 million groups. At the same time, the free web-hosting service GeoCities was home to about a third of the fan sites that Celine Dion’s team linked to on her official website. Launched by Yahoo in 1994, it was a hotbed of fan pages, dominated by Harry Potter, The X-Files, Sherlock Holmes, and Hanson. According to an incredibly buggy search engine released last year to help former users travel back in time, there were about 1,200 pages dedicated to Celine Dion.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community