Now the revised entry for racism has finally arrived, included in the online update Merriam-Webster published yesterday. As promised, the entry underscores some nuances, though the revision is not a complete rewrite. As before, the first definition given relates to personal belief and attitudes. But the revised second definition—“the systemic oppression of a racial group to the social, economic, and political advantage of another; specifically: white supremacy”—better highlights what Mitchum was looking for. Additionally, the entry is now enriched by illustrative quotations from such writers as Angela Y. Davis, bell hooks, Mariana Calvo, and Imani Perry, and the activist Bree Newsome.

When Mitchum’s appeal to Merriam-Webster attracted news coverage in June, many commentators portrayed the story in broad strokes as “the dictionary gets woke.” Depending on one’s political perspective, that might be seen as either a laudable step in the path to progressive enlightenment or as a capitulation to the forces of political correctness. But a closer look at how Merriam-Webster’s definition of racism has evolved over time reveals a much more complex narrative.

Racism and racist are surprisingly recent additions to the English lexicon. You won’t find those words in the writings of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, or Abraham Lincoln. While the Oxford English Dictionary currently dates racism in English to 1903 and racist to 1919, the terms were still rarely used in the early decades of the 20th century. The pioneering civil-rights activist and journalist Ida B. Wells, for instance, instead used phrases like race hatred and race prejudice in her memoir, Crusade for Justice, which she began writing in 1928 but left unfinished when she died three years later.

When Merriam-Webster published the second edition of its unabridged New International Dictionary, in 1934, racism was nowhere to be found. The editors did include another, related term, which was more popular at the time: racialism, defined as “racial characteristics, tendencies, prejudices, or the like; spec., race hatred.” But racism was not yet on the radar of the lexicographers diligently at work at Merriam-Webster’s Springfield, Massachusetts, office.

Read: The dictionary definition of ‘racism’ has to change

That all changed thanks to a perceptive observation by one member of the editorial staff named Rose Frances Egan. Egan, a graduate of Syracuse and Columbia who studied the history of aesthetics, came on board as an assistant editor for the second edition of the New International Dictionary. She was also tasked with writing entries for Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms, which she worked on for several years before its first edition was published in 1942.

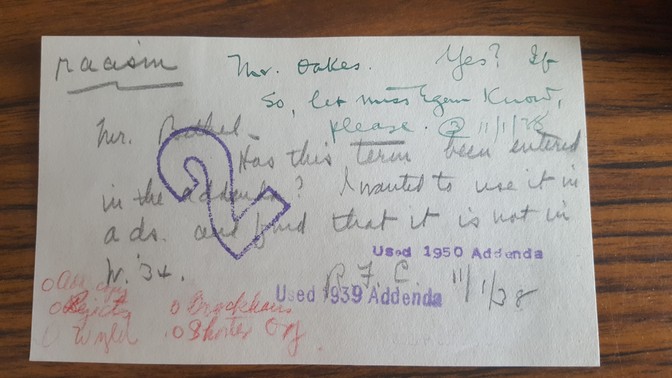

A handwritten slip tucked away in Merriam-Webster’s archive tells the story. (Before the advent of email, interoffice communication among the editors in Springfield would typically be carried out by exchanging notes on pink slips of paper, still known affectionately as “the pinks.”) This particular slip, dated November 1, 1938, was written by Egan, who asked a fellow editor, John P. Bethel, about the status of the word racism. “Has this term been entered in the Addenda?” Egan asked Bethel. “I wanted to use it in a ds. and found that it is not in W. 34.”

John Morse, a former president and publisher at Merriam-Webster, guided me through the obscure in-house notations on the slip with the eagerness of an Egyptologist deciphering the Rosetta Stone. Egan knew that there was no racism entry in the 1934 Webster’s New International but was inquiring whether it was slated for future printings as part of the Addenda, the section in the front of the dictionary for new words that came to the editors’ attention too late for inclusion in the main text. When Egan said she wanted to use it in a “ds.,” that was short for discriminated synonym, the term of art for the items considered in the entries of the Dictionary of Synonyms that Egan was hard at work drafting. Any word used in a secondary work like the synonym dictionary, according to Merriam-Webster policy, should also be found in the flagship unabridged dictionary.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community