In April 1954, James Beard flew from his home in New York to San Francisco and set out on a culinary road trip across the western U.S. The prolific cookbook author was about to turn 51, and feeling stuck in a loop of magazine deadlines, TV appearances, and product shilling. The hustle was constant, satisfaction elusive. “I am pooped, bitched, bushed, buggered and completely at sea with ennui and bewilderment,” Beard wrote to one of his road-trip companions before they left. “But off we go.”

As John Birdsall describes in his new biography of Beard, The Man Who Ate Too Much, the Portland, Oregon–born cook had spent much of his career trying to retool French classics for American housewives—boeuf bourguignon with a transatlantic accent. Like a lot of white American gourmands of the time, Beard saw France as the ne plus ultra. “Thus far,” writes Birdsall, “James had fumbled at articulating a true American cooking.” This road trip finally turned his gaze homeward. En route, Beard and his friends ate blue cheese made in Oregon with Roquefort spores; baked shad and apple crisp; Swedish pancakes and French 75s. These meals electrified him. They amounted to his kind of American food—far from kitschy TV dinners, these dishes used local ingredients and bore an unforced resemblance to European classics. And, writes Birdsall, they confirmed Beard’s growing belief that “all good food in the present bore an echo of [his] past.”

Over the next three decades, Beard chased that echo through countless magazine stories, cooking classes, and dozens of books, including kitchen bibles whose titles claimed definitive status (A Complete Guide to …) until Beard’s name alone did the trick (Beard on Bread). The New York Times dubbed him “the Dean of American Cookery.” Beard was also gay, a fact hidden from his public until the last years of his life. In The Man Who Ate Too Much, Birdsall aims to queer the record; he works to show that this man, who became famous during a brutally antigay stretch of U.S. history, fathered a whole branch of American cuisine—one contemporary readers might associate with artisanal bakeries, farmers’ markets, and Chez Panisse. “Though he was always present in American kitchens,” Birdsall writes in his preface, “Beard carried himself like an outsider, an alien with a secret, a man on a lonely coast who told us we could find meaning and comfort by embracing pleasure.”

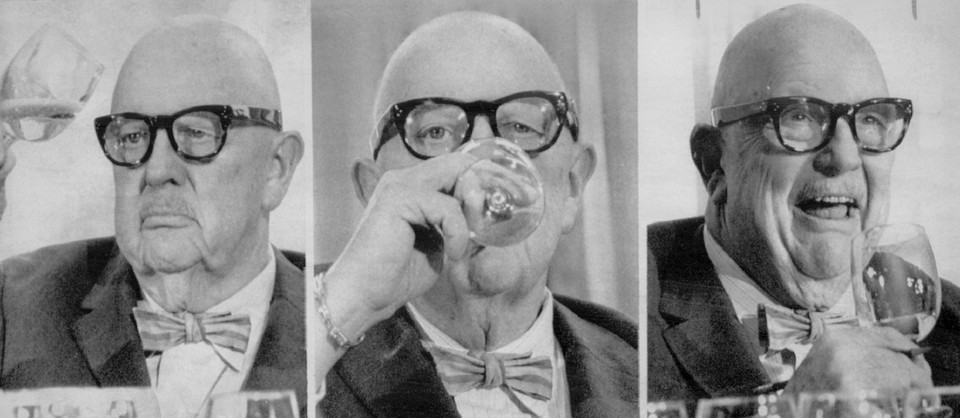

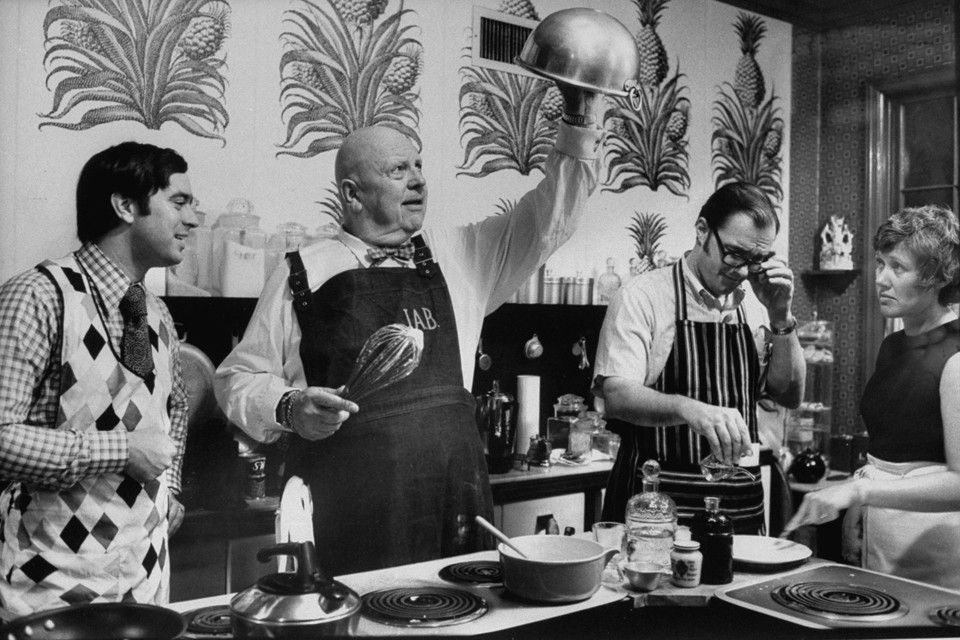

Birdsall surmises that readers see Beard as an “institution,” perhaps equating him with the James Beard Foundation and Awards established after his death in 1985. So he turns the icon—tall, bald, and bow-tied—back into a person: He lingers on Beard’s well-fed, emotionally starved childhood, his struggles as a fat man, the pain of sexual rejection and antigay bigotry. We get fun James and petty James, James as self-plagiarist and bitter competitor, who sometimes used the unacknowledged labors of his collaborators to burnish his own image.

Being ensconced in this very specific world is a pleasure, especially with a guide so invested in Beard’s emotional life. The book loses its footing, though, when it tries to turn biography into foundation myth—as though Beard’s vision for American food could be equated with what American food, in all its messiness, actually was. “He embodied America’s culinary identity for most of the second half of the twentieth century,” Birdsall writes. “James Beard was American food, its pleasures and excesses, its beauty and simplicity.” Beard was a famously big man, in body and personality, with a verve for eating that gave his American fans permission to love it too. But to be American food—has there ever been one person big enough for that?

James Andrews Beard was born in 1903, and reared on a West Coast where San Francisco was called the “Paris of the West” and French-cheffed restaurants were the pinnacle of glamour. His English mother ran boardinghouses before having a child, and James spent his childhood tagging along with her to dinner parties and trips to the seashore; she wasn’t particularly warm, but she gave James the gift of her palate. (James’s father, a taciturn American customs officer, was something of an emotional void.) Like a lot of well-off Portland families at the time, the Beards employed Chinese servants. In one of the book’s tenderest passages, Birdsall recounts how the family’s Cantonese cook, Jue Let, nursed young James back to health by spoon-feeding him chicken jelly. Mostly, James’s world was one of butter-and-marmalade sandwiches, clam chowder, and towering birthday cakes heaped with coconut and white frosting, reflecting his mother’s tastes and the bounty of the Pacific Northwest.

The book tracks Beard closely through a series of failed attempts. He enrolls in Reed College, gets caught hooking up with a popular male teacher, and is quietly expelled—a trauma, Birdsall writes, that haunted Beard for the rest of his life. Beard attempts to reinvent himself in Europe as an opera singer and actor, but it’s not until he’s 35 and living in New York that his food career begins. He meets a wealthy gay man who hires him as a live-in caterer, someone to dish up finger foods and martinis during the cocktail parties that doubled as safe meeting places for Manhattan’s gay elite.

Food is a haven for Beard in even his lowest moments, and Birdsall, a lovely writer, honors that with delicate reconstructions of flavor: He describes the “smokiness and moldy specter” of a ham, and calf’s tongue “poached and shaved, the delicate curls wrapped around balls of creamed Roquefort.” In 1940, Beard is working at a catering company when he gets his first chance at a cookbook. He writes a guide to hors d’oeuvres in which he takes full credit for his company’s star dishes—including a now-infamous recipe for a mayonnaise and raw-onion sandwich on brioche, edges dusted with chopped parsley. With that, Beard is off like a rocket, sometimes pushing out multiple cookbooks a year over the next few decades.

Read: The myth of ‘easy’ cooking

Birdsall pulls no punches about Beard’s failings, particularly his stinginess with acknowledgments, and in the process sketches a blueprint for how a public personality is built. Beard reportedly enlisted a friend to help him develop a huge cooking tome—then neglected to pay her, or even thank her in the book. He stole recipes. His prose was apparently sloppy: Birdsall discusses Beard’s friend and “uncredited writing collaborator” Isabel Errington Callvert, who pre-edited his magazine stories before he filed them. Even Beard’s most personal books, such as 1964’s Delights and Prejudices, were heavily edited or ghostwritten by people whom he paid only a fraction of his fee, and who played a role in constructing the Beard readers likely remember today. (Somewhat ironically, Birdsall quotes regularly from these books to shape his narrative, even as he admits that any memoir of Beard “would have to be semimythical, to fill in the parts he couldn’t tell.”)

If some of the mythmaking was engineered by Beard himself, some of it was imposed, or at least enabled, by the nascent food media. In the lionizing 2017 PBS documentary James Beard: America’s First Foodie, the filmmakers interviewed one of Beard’s editors at Knopf, Judith Jones, about what the industry was like in the 1950s. “There wasn’t a food world in the sense that we have one today,” Jones said. “It was the women’s magazines, and they had a lot of recipes, fast and easy.”

Beard stood out because he was a rare man in an industry that catered to, and mostly employed, women. To capitalize on that, editors and a small army of ghostwriters suppressed the campy charm that ran through his earliest writing. Postwar gender roles didn’t leave a lot of breathing room. “It was no time to be anything but a sexless bachelor with a crisp, professional voice, too focused on work or the singular pursuit of fine living to think about marrying,” Birdsall writes. For most of Beard’s life, being outed would have meant professional ruin. In exchange for passing as a straight man, though, Beard got something that women recipe writers and authors of texts such as Joy of Cooking had not: He got to be treated as an authority.

Read: Uncovering the roots of Caribbean cooking

Beard’s constructed image was something of a devil’s bargain. And women such as Julia Child—whom Jones introduced to Beard—and Alice Waters, Ruth Reichl, and Edna Lewis, would later be treated as experts in their own right. Still, in the blatantly patriarchal media landscape of the 1940s and ’50s, it’s not a coincidence that the first model for the modern American-food personality would be a man. Beard could write for pulpy men’s magazines as “Jim Beard.” The fact that he was a man would later make it more acceptable for men to enroll in his cooking classes. Beard could be something that American women could not: a Great Man, awarded the kind of stature that made it worth editors’ while to iron out rambling copy. It also brought in sponsorship dollars. In a mid-century flour ad excerpted in the PBS documentary, Beard looks straight into the camera as a manly voice-over intones, “When this man speaks, master chefs listen.”

Beard, for his part, seems to have embraced his status as paterfamilias. “More and more, he regarded his recollections as a kind of national seed bank of food memory,” Birdsall writes. But the notion of Beard as the keeper of America’s culinary flame merits more skepticism than the book allows, especially when it comes to American cuisine’s non-European influences.

Birdsall makes clear that Beard was focused on the food of European immigrants, a quiet acknowledgment that Beard didn’t seek to speak for all Americans or all their foodways. When he relates the story of a bad New York Times review for one of Beard’s books—in which a critic seemed to scold Beard for glossing over the country’s culinary diversity—Birdsall hits back, saying that Beard didn’t think he stood for everyone; he was just writing what he knew. Yet throughout the book, Birdsall also essentially describes Beard as the soul of a national cuisine, with no real competing narratives to that central one. Caveats are no match for this grand thesis.

Read: How American cuisine became a melting pot

You can see the limitations of the Beard-as-American-food approach in Birdsall’s discussion of the 1972 cookbook, James Beard’s American Cookery, which included recipes for dishes such as cream of tomato soup, chilled poached shrimp, and snickerdoodles. Birdsall writes that the book was in part Beard’s “lament” for the country’s natural resources, a tribute to the bounty of his childhood trips to the seashore. But that wasn’t the only way to read it: At a time of protest and political upheaval, the book “was bedtime reading for Americans who found comfort in its implicit celebration of traditional values … an 875-page elegy for America.” Birdsall doesn’t say which Americans those might’ve been. In the harsh light of 2020, it’s hard to read about traditional values and elegies for America—delivered during the era of Black Power and rising immigration from Asia, Africa, and Latin America—and not assume that the cookbook reader who yearned for these things would be white.

Also notable is that, of the many significant figures mentioned throughout The Man Who Ate Too Much, only two likely wouldn’t trace their roots back to Europe, and both were domestic workers, employed by Beard or his parents: Jue Let, his family’s Cantonese cook, and Clayton Triplette, a Black and Iroquois gay man whom Beard hired as a housekeeper and manager in the 1950s. They were consequential people in Beard’s personal life, but we don’t get a good sense of how influential they were, if at all, to his most fundamental ideas about America’s culinary identity.

Birdsall is at his best when he focuses squarely on Beard—unearthing his connections to other queer luminaries, and tracing the lines between his memories and his palate. Perhaps a deeper consideration of non-Eurocentric American cooking is too much to ask of a book about this one man’s life. But Birdsall seems to want to tell more than the story of a life, and that’s where he overextends—claiming that Beard embodied American food, instead of letting his subject be important enough on his own.

Birdsall began writing The Man Who Ate Too Much after he published an essay in Lucky Peach magazine in 2013, titled “America, Your Food Is So Gay,” about the queer culinary aesthetic of Richard Olney, Craig Claiborne, and Beard, three gay white men acknowledged as masters. Birdsall couldn’t have known that his book about Beard—this asterisk on the canon—would land in a year so hostile to the idea of a canon itself.

In the past eight months, the pressures of the pandemic and protests against anti-Blackness have forced the culinary world’s skeletons out of the closet. Workers have pushed back against alleged inequity at publications such as Bon Appétit and at restaurants across the country. The Beard Awards were postponed, then curtailed, whipsawed by accusations about the “personal or professional behavior” of some of the nominees, according to The New York Times’ Pete Wells, as well as public complaints from James Beard Foundation employees over pay disparity and working conditions. (Plus, as Wells reported, not a single Black chef had won a restaurant award.) Birdsall, who has been both a judge and a member of nominating committees for the Beard Awards, as well as a recipient of its writing awards, responded to the chaos in a Washington Post op-ed. He wrote that Beard would have hated the awards: “I believe that if Beard were alive today, his voice would be the loudest calling for radical changes to the ceremony that bears his name.”

It’s a nice thought. And, arguably, it misses the point. One takeaway from this year of upheaval is that, for too long, the same kinds of voices—Beard’s included—have been amplified above others. He may have felt like an outsider, but Beard still helped build the establishment that now faces a reckoning. Nonetheless, his life is an example of an enduring truth: American food, that undefinable thing, is best represented by the people who cook it and love it. There are just a lot more of them than history tends to remember.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community