I.

So I first heard about Shimmel Zohar from Gravity Goldberg—yeah, I know, but she insists it’s her real name (explaining that her father was a physicist)—who is the director of public programs and visitor experience at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco. She was calling to tell me about an upcoming show—the inaugural exhibition of a recently discovered trove of work by Shimmel Zohar, a Lithuanian immigrant photographer (and contemporary of Mathew Brady), who had done for the Jewish community of Manhattan’s Lower East Side what, generations later, August Sander would do for Weimar-era Berlin: create a complete photographic inventory of professions and types. Or maybe not. There was, she suggested, some slippage in the whole backstory, and they were trying to find someone who might be willing to look into the matter, perhaps even for an afterword to the show’s catalog, which was on the verge of publication. Might I, she wondered, be interested?

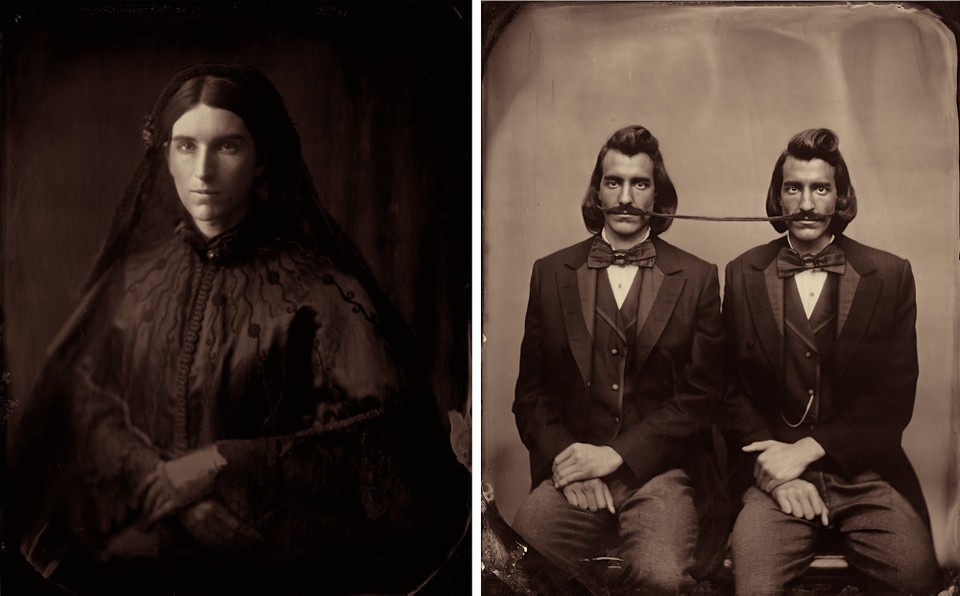

I was intrigued. Which is how it happened that, several days later—this was all a few months before the onset of the global pandemic—I found myself on a transcontinental flight to Los Angeles to meet a man named Stephen Berkman, who, according to Gravity, had been involved in bringing the Zohar archive to the museum’s attention. As I flew over the Great Plains, I reviewed an early digital version of the exhibition’s catalog. Skirting past its odd title (Predicting the Past) and its even odder subtitle (Experiments in Reverse-Prescience), I tumbled into a cavalcade of sepia photographic plates, not a few of them drop-dead gorgeous, many of them hauntingly nostalgic, and others, coupled with deadpan titles such as Itinerant Phrenologist and The Baroness of Babylon Boulevard, downright drollarious. The catalog began with a portrait of a young advertising maiden, standing at earnest attention in a long dress alongside a Zohar Studios banner, and wearing—could those be roller skates on her feet? I moved past A Woman Hand-Knitting a Condom (presumably as full of holes as the Zohar story she seemed to have gotten herself involved in). In another plate, a man held forth A Downtrodden Banana (a rather large lump atop his head, perhaps an allusion to his own recent slip on said banana’s peel). A military commander brandished not a downtrodden banana but The Root of All Evil, and an actual root at that. There was a doleful old man identified simply as a Blind Mohel, and a few pages after that, a solicitously eager young Merkin Merchant. A perplexed gentleman pondered a ventriloquist’s dummy’s head perched atop a stick at the end of his outstretched hand—The History of Dread—which echoed an earlier photograph, titled Shtetl Shtick, in which a sad-looking Hassid cradled a diminutive doppelgänger on his lap—all prompting the age-old question (especially fraught when the enterprise is about “predicting the past”) of just who is ever the ventriloquist and who the dummy.

On and on I paged, past dozens of other such photographic productions, ultimately coming to rest at a picture of the New York studio of our apparent host, Shimmel Zohar himself, the master, in the very act of photographing the girl wearing the roller skates.

So you can perhaps imagine how I was beginning to wonder, as the plane started banking toward its final descent, just what the hell was going on here. The dozens of uncredited pages of pedantic, digressive commentary (which at one point described the photographic work as “post-humorous”) did not help in the least. And Shimmel Zohar—what kind of name was that, anyway, and how had nobody ever heard of the guy until now? And just what was the story behind his post-humorous resurrection?

With questions like these spin-cycling through my head, I alighted at LAX.

II.

Stephen Berkman turned out to be living on a lovely street of elegantly dispersed single-family homes in the gently rising Dundee Heights neighborhood of northern Pasadena, in what may have been the least elegant dwelling on the entire block. The front yard’s xeriscape was overgrown, and two cluttered pickup trucks were incongruously slotted into the driveway. “Yeah,” Berkman explained as he emerged from behind the far gate, “my life partner, Jeanine, bought the first, and I thought it was great, so I got myself one too.” Berkman proved to be a shortish fellow with disconcertingly bushy muttonchops and a joshing, amiable demeanor. “Dundrearies,” he said, following my gaze. What? “The technical name for this kind of sideburn. Very popular in the Victorian era.” His own dangled well past his clavicles, giving Berkman the appearance of a jovial garden gnome.

A gnome who now bid me follow him into the back of the property, through an opening in a dilapidated wooden fence. If the front yard had seemed ramshackle, the back was a boneyard, strewn with truncated mannequins, disabled gadgets, warped planks of plywood, disintegrating plaster cornices, and mysteriously jumbled piles of bric-a-brac. “Yeah,” Berkman apologized as we clambered toward an alleyway cut between two outbuildings, his library-cum-studio hangar to one side and a garage darkroom to the other. “But here is my main workspace,” he continued, at which point I interrupted to ask if I could first use his bathroom. “Oh, sorry, of course.” We doubled back to a side entry into the main house and he pointed the way, advising, “But be careful, the door has lost its handle,” the first of many comments that could easily have served as an alternate title for this entire essay.

I soon wended my way back to Berkman’s atelier, a dim, cavernous den and hoarder’s paradise that made the outer boneyard seem pristine by comparison: Rickety tables were covered with ornate optical and musical contraptions in varying stages of disassembly; cardboard boxes overflowed with Victorian costumes and comatose puppets. Serpentine cables coursed underfoot. Wigs dangled from above. “Be careful about putting anything down over there,” Berkman advised from the distant northwest corner of the hangar, where he was puttering about in a relative aquarium of light, framed by wide skylights and a wall of gridded windows and folding glass doors—a meticulous replica, it momentarily seemed, of Zohar’s own studio as it had been portrayed in that last of the catalog’s plates. “Otherwise, you probably won’t be able to find it for months.”

Somehow I surmounted the clutter and made my way over to the open space where Berkman was tinkering with a big wooden camera mounted atop a sprawling tripod. I took a seat in an elegant chair at the far end of the camera’s focus. “So listen,” I began, as Berkman installed himself on a rickety stool. “I’m going to want to get into this Zohar fellow in a moment—how you became aware of him, and more exactly who he is to you, or you to him. None of that is quite clear in the catalog.” “Ah,” Berkman said, raking his dundrearies in consternation and shifting nervously, “that’s all a very complicated situation. Perhaps the less said the better.”

Okay, we’ll get back to that, I said. Maybe we could start with his own story. “Well,” Berkman began, “I was born in 1963, in Syracuse, New York—we all have to be born somewhere—though our family moved out to Northern California the very next year, to Santa Rosa and then to Redwood City. My parents were both very engaged with their Jewishness—conservative; the family kept kosher—their parents all having emigrated from Lithuania, fleeing pogroms, back in the teens and ’20s, and all of that generation spoke Yiddish.” His mother was a short-story writer (who recently got a doctorate in Jewish studies from the Spertus Institute, in Chicago), and his father is an accountant, still practicing, whose clients have included a succession of famous performers—“for example, Joan Baez, who became a family friend and for my bar mitzvah gave me a Rolling Thunder Revue T-shirt, which I believe I still have, somewhere back there.” He started to get up to look for it, but I said never mind—I believed him.

Berkman himself had not been particularly captivated by Jewish themes in his early days—“Hebrew school was an existential trial”—though in a generally goyish environment, he began to develop a sense of himself as an outsider, which he came to cherish. In school, he was given to passionate immersion in the things he cared about and utter indifference to almost everything else. At the age of 5, he received a microscope as a present. He proved to be less interested in the things one could see through the lenses than in the optics of the microscope itself. By age 10, he had his own Kodak 110 camera and began experimenting with 35-mm stills in a rudimentary darkroom. From the start, he recalled, he had a sense of time itself as somehow the focus of his passion: “To this day, the moment the seized image swims up from out of the dark feels utterly magical.”

He observed how his growing interest in photography was virtually simultaneous with the dawning of an interest in Judaism, though in a cultural rather than a religious sense, and particularly in the shtetl culture of Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. “For that matter,” he went on, “I think a good part of what would become an all-consuming interest in the 19th century grew out of the fact that it was the century when chemical photography was itself being invented.”

In general, he insisted, his was a happy childhood, devoid of any real traumas or hardships. “I mean, I was short—at the end of high school I was voted the shortest in my yearbook, when what I’d really been going for was best hair. But I got along with people and was well liked, nothing really to complain about. I’ve never had to go in for therapy. No dark wells of anguish, the sorts of things that other artists seem able to draw upon for inspiration. Which may explain, for example, why I have so much trouble fleshing out any sort of alter ego.”

We’ll get to that, I assured him. But maybe he could first finish his own story. “Well, by 15 or 16, I’d pretty much decided on a career in photojournalism and was even contributing photos to local newspapers. Though, on a separate track, I was getting more and more interested in 19th-century photography, and I remember how even then I was spending a lot of time thinking about whether it would be possible to replicate old lenses and cameras and chemical compounds so as to be able to create new images exactly the way the pioneers had.”

Funny, then, that when he reported to college at San Francisco State University, his education went in neither of those two directions. He majored in film, but in cinema rather than photography, and by the end of his time there, he’d convinced himself that he wanted to aspire to more conventional narrative feature films pitched to wider audiences. So he pursued that angle, moving from SFSU to study film at De Anza College, in Cupertino, which is where he met Jeanine Tangen—a Minnesotan of Norwegian stock, herself just out of UC Santa Cruz (where she’d received a degree in photography)—in their very first class. The two have been together ever since. Jeanine went on to a successful career as a writing assistant to directors of both long and short films, and Berkman, who teaches at Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design, began directing commercials and music videos, the initial rungs on the conventional ladder toward more ambitious feature projects.

Except that his heart wasn’t really in it. He—with Jeanine—kept being pulled back into the 19th century, and in particular the astonishing first 60 years of still photography, “when all the subsequent genres were being developed right there before your eyes.”

By 1995, Berkman was a member of the Daguerreian Society, a group organized by collectors and scholars of daguerreotypes. Around that time, he and Jeanine attended a big exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the photography of the early French master Nadar. They were overwhelmed by the extraordinary detail and haunting tone that Nadar had achieved with the wet-collodion process he championed. Returning to Pasadena, Berkman reequipped his darkroom and began experimenting with the process himself. It remains the main technique he employs to this day.

III.

“Here,” Berkman said, “I’ll show you how the wet-collodion process works.” He checked a few details on the boxy camera atop its tripod and then, sliding out the empty plate holder, he ducked under the black hood and gazed upon the frosted-glass panel onto which the camera’s front lens was now projecting an image of me, upside down. He adjusted my pose, had me try a few variations, settled on one, and slid the accordion bellows connected to the front lens forward and back a few times, tweaking the focus, until he had everything just right. “Okay,” he said, “first we have to go prepare the glass plate.” He led me outside through the folding glass doors and across the narrow alleyway into his converted-garage darkroom, which was even more cluttered than the library warehouse, and pitch-black. “Be careful,” Berkman cautioned, “and try to follow in my footsteps. Walk like me” (another great potential title).

Once we’d made it over to the workbench/sink on the far side of the darkroom, Berkman flicked on a dim light, set the plate holder to the side, and reached down into a square wooden storage box on the floor, gingerly pulling out a single clean, polished pane of glass, which he now proceeded to clean and polish a bit more. He explained that “the wet-collodion process was developed in England in the early 1850s and represented a considerable advance on the daguerreotypes and calotypes that had immediately preceded it. For one thing, it allowed photographers to generate paper copies of the original image in magnificent detail, with exceptionally lush tonalities and in previously unheard-of quantities. And the key to the process was this”—he reached for a jar of a red viscous liquid that looked a bit like thickened cherry Kool-Aid, and swished it around. “This is the collodion mixture, made from a carefully calibrated blend of collodion, which is basically gun cotton dissolved in nitric acid, and is otherwise used in various medical contexts to this day, mixed with anhydrous ether—190-proof alcohol—along with tinctures of potassium iodide and cadmium bromide. I mixed up this particular vintage about a week ago and then left it to settle and cure.” He unscrewed the lid. “Here. Smell it.” The mixture did indeed have a sharp, medicinal aroma. “The first time I got a whiff of collodion,” Berkman confessed, “I was hooked for life. Really, it was a transformative experience. The scent was both sharp and sweet, but with dimension, with depth. In fact, it transported me clean back to one of the peak moments of my childhood, when I was first exposed to laughing gas at my dentist’s.”

Berkman returned to the business at hand. “Okay. Now we take the pane of glass and carefully hold it out by its edges horizontally, like this, and we pour a puddle of the collodion mixture onto the center of the glass. As you can see, the stuff’s like a light syrup and quite sticky. Anyway, we gently manipulate the pane so that the puddle spreads evenly over the entire surface, and this will serve as the binder for the next step, in which we now dip the treated glass pane”—he opened a narrow wooden box off to the side—“into this silver bath, a solution of distilled water with 9 percent silver nitrate. We close the box’s lid and leave the collodion-sheathed glass in there for about four minutes to absorb a layer of evenly diluted silver, the layer which will in turn presently absorb the light pouring through the lens bellows when we put the treated glass back into the camera.”

While we waited out the four minutes, Berkman mentioned that, in addition to the aroma of the collodion mixture, he had been drawn specifically to the use of glass negatives in the wet-collodion process. “I’ve already mentioned how utterly magical the whole procedure continues to feel for me to this day, this arcane, secret activity undertaken in the dark, but it also struck a specifically Jewish, or rather Jewish-mystical—a Kabbalistic—chord in me, back in those days when I was delving deep into shtetl culture at the same time. Which is to say, the shattering of the glass vessels at the beginning of Creation.”

This happened to be something that I, too, had studied, in college (at UC Santa Cruz, as it happens). A major question for the Kabbalists of the 15th century, especially those gathered around the great Rebbe Isaac Luria in Palestine, was how Yahweh could have created anything, as he was already everywhere and there was no room for anything else—a conundrum they resolved by suggesting that just before the Creation, Yahweh breathed in, as it were, through a process called the tsimtsum, absenting himself from a portion of his cosmos, where he’d set up a sort of apparatus consisting of 10 great interconnecting glass vessels, into which he would then be aiming the overwhelming light of his power and beneficence as a first step in the Creation—only something went disastrously wrong. The glass vessels could not contain the sheer intensity of the surge of light and shattered into billions of tiny shards that now drifted into the dark abyss—this all being another way of thinking about the Fall, a Fall that somehow left Yahweh wounded as well, such that he could no longer repair things on his own. And so it became the work of human beings, through tikkun olam, a sort of contemplative action across time, to help mend the world.

“Yeah, right,” Berkman concurred after I offered my summary. “So maybe you can see how the collodion process—this near-alchemical devotional activity blending themes of light and dark and glass and breakability—might have rhymed with some of those other growing obsessions of mine.

“Okay,” he continued, “that’s been about four minutes. So now we have to move quickly, because once we pull the glass plate out of the silver bath, we have to accomplish everything else—placing the plate into this light-tight holder, taking the holder back to the camera, sliding it in, getting you all set up again in that pose in your chair, pulling aside the dark slide separating the plate from the accordion bellows and removing the lens cap, thereafter exposing the plate for about 40 seconds, during which you’ll have to keep as still as possible, then sealing things up again and bringing the light-tight holder right back here to the darkroom for development, which involves a whole other process—and all of that before the plate’s silver-fused collodion skin dries up, after which it becomes useless. Which is to say, we’ll have about 10 minutes total.”

And that’s pretty much what then happened. We rushed back, I resumed my pose, tilting my face just so and breaking into what I fancied to be a fetching smile, whereupon Berkman, looking up, shouted, “No smiles! This is serious business! Happiness is not part of the equation. Seriously, things never work if you smile!” (four more great alternate titles, come to think of it, one right after the other). I sobered up and froze. He removed the lens cap and tapped a stopwatch, which proved not to be working, so he just said “Now,” and the world seemed to hold its breath, stock-still, for an eternity, as he counted by fives to 40, using Roman numerals (“eye … vee … ex … ex-vee … ex-ex”), after which he replaced the cap and retrieved the plate holder.

Back in the darkroom, Berkman nudged the exposed plate out of its holder. I’ll skip over all the ablutions he performed. But I will note that watching the image, my own image, slowly swim into being from somewhere seemingly far, far behind the transparent glass pane, was, as Berkman suggested, a spiritually tinged experience. Furthermore, the image that emerged seemed to be coming from somewhere in history—as if I myself had been teleported back to the 19th century. Or rather, maybe, it seemed simultaneously ageless and yet possessed of exceptional presence and immediacy. Stammering, I tried to express all of this to Berkman, and he replied, “Yes, what it has is duration. It has time in it: not least the time of your sitting there.” He paused, shaking some of the distilled-water rinse off the finished plate, before placing the plate on a rack to dry.

IV.

So listen, I said, as we now settled back onto our respective seats in the studio: When exactly did what had been a hobby, off to the side of his commercial and filmmaking and teaching careers, flip places and become his defining passion? “Well, by the late ’90s, 1997, ’98, out on my commercial shoots, for example,” Berkman replied, “I found myself increasingly thinking that all I really wanted to do was get back home so I could bury myself in the latest issue of The Collodion Journal. And within a few years, I had in fact managed to figure out a way of blending those two sides of my life, at least part of the time, starting with a job where I got hired to join Anthony Minghella’s shoot of Cold Mountain on location in Romania—as supplier of wet-collodion tintypes for its American Civil War scenes—and from there that sort of hybrid activity became an increasing source of livelihood.” Since Cold Mountain, Berkman has become perhaps Hollywood’s leading go-to man for that kind of plot-driven antiquarian photographic portrayal; he even had a bit part as a traveling Jewish photographer in The Lone Ranger.

I doubled back, doing the math: 1997, 1998, 2020. “The people at the Contemporary Jewish Museum,” I said, “told me that their upcoming show devoted to Zohar Studios is going to be the culmination of more than 20 years of your own investigative lifework. So it must have been somewhere in here that—how shall we put it?—Shimmel Zohar first entered your life. How did that come about?”

Berkman looked back at me, thrumming his dundrearies, uncomprehending.

Seconds passed (talk about duration). “I don’t understand the question.”

“Well, how did you first hear about him? I mean, it clearly must have been quite a discovery.”

“Well, yeah, but that’s the kind of thing I’d really rather not go into. It’s a complicated story and not all that interesting, and I don’t want to call attention to myself. I don’t want to get in the way of Zohar’s achievement, the studio’s story. I merely think of my role as being a kind of facilitator in bringing that story to the world’s attention.”

A facilitator? (Now it was my turn to look at him uncomprehending.) “The catalog begins with a procession of remarkable images: Where did you find them? What’s their backstory?”

“I didn’t ‘find’ them, exactly. This book is my tribute to the work of the Zohar studio and the historical imagination.”

“Tribute? Does that mean, for example, that you compiled the voluminous commentary on each of the plates?”

“Actually, no. That was the Professor.”

The Professor?

“Yeah, Professor De Leon.”

Professor De Leon?

“Yeah, Professor M. De Leon. He was funny that way. He always used an initial instead of his first name.”

“Okay. Let’s set the Professor aside for a moment. We’ll come back to him. But the chapter called ‘The Glass Requiem,’ that’s the place in the catalog where we finally get a tranche of actual biographical information about Shimmel Zohar: how he was born in Zhidik, Lithuania, in 1822, and arrived in New York in 1857, and eventually established a photographic studio on two floors of 432 Pearl Street, on the Lower East Side, a neighborhood teeming with Jewish immigrants. How he enjoyed some success but then suddenly abandoned his studio and hit the road, becoming an itinerant photographer touring America, perhaps in search of Flora, his former showgirl paramour (and, who knows, maybe even the roller-skate girl), planning to return to New York within a year but then simply vanishing, never to be heard from again. So was it the Professor who wrote ‘The Glass Requiem’?”

“Oh no, that was Jeanine and me.”

“Right. But how did you two first hear about Zohar? Where did you track down all that information, and how did you find the photographs?”

“Well, we didn’t, exactly. You’re reminding me of the clerk at the copyright office early on, when I sent one of the photos to be copyrighted in the name of Shimmel Zohar, and they wrote me back, ‘Yeah, but who are YOU?’”

“Well, exactly: Who are you to Zohar, and who is Zohar to you?”

“Really, what does it matter? You’re asking the sorts of questions I’ve spent the past 20 years avoiding, and actually kind of dreading—why are you being so insistent?”

“Because who wouldn’t be? Anyone curious or indeed fascinated by this amazing discovery would be eager to hear about the person who made it and how he did so.”

“But that’s just it. I don’t want to get in the way. It shouldn’t be about me. I suppose, too, the thing is that by nature I’ve always been an openly secretive person.” A what? “And anyway, I prefer things to be more evocative and less literal. I like to traffic in moods rather than specifics.”

When it came to Zohar, Berkman wanted neither to have his cake nor to eat it. Or maybe, like Yahweh, he was attempting to absent himself to make room for his creation. Berkman smiled in sympathy at my exasperation. “Myself,” he said, “I always liked Guy Davenport’s characterization of parts of his work as ‘assemblages of history along with necessary fictions.’”

It had been a long day. We’d clearly arrived at a sort of impasse, in which the harder I pushed, the deeper Berkman receded into his stubborn shell. In good-natured defeat, I suggested we call it a day and reconvene the next morning.

V.

Upon my return the next day, I found Berkman back in his studio, preparing his camera for a second portrait of me, this one in profile. “Remember,” he said, “you are going to need to sit completely still for over 40 seconds. Generally speaking, the great thing about these long exposures is how they break down the subject’s resistance and you get to drill down to the real person. Okay, here we go.” He removed the lens cap, and as I sat there, motionless, the seconds ticking away, I hoped that maybe the same rule would apply today to my own attempts to overwhelm his resistance.

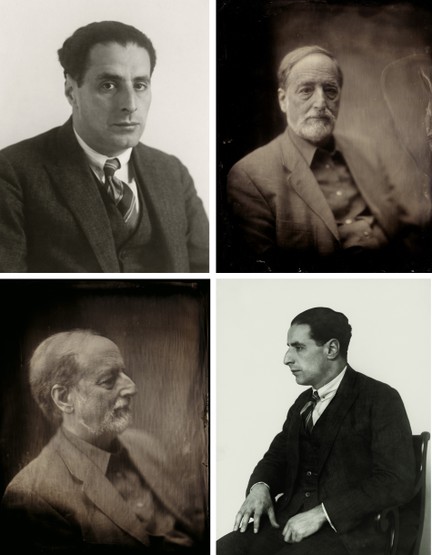

Weschler by Stephen Berkman.

At any rate, the new portrait, once it was developed, proved yet more deeply unmoored in time than the previous one, as if I were somehow channeling my inner Abraham Lincoln. And in fact the effect was even more unsettling than that. Recalling Gravity’s reference to August Sander (and she’d apparently been channeling Berkman himself), I remembered that back in Berlin, in the 1920s, my grandfather, the composer Ernst Toch, had agreed to pose in two photographs for the Weimar master’s typological inventory, as a representative of “Artists,” and as I brought up those images on my cellphone, both Berkman and I were startled by the resemblance. For a moment, we couldn’t help but wonder who had been anticipating whom, and just who was whose ancestor.

As we resumed our seats—wooden armchair for me, rickety stool for Berkman—I girded myself for yet another round of metawrestling. Except that suddenly the match seemed to have ended on its own.

“Yeah,” said Berkman. “So Jeanine and I were talking last night about your insistence that I tell you the whole story about how Zohar first came into our lives, as you put it, and she basically agreed with you—you and the readers do need to be given some sense of all that. And so, notwithstanding all my misgivings about doing so, I pulled together some materials”—he reached for a manila folder—“and am ready to go through the whole saga.”

He paused, as if gathering up the sheer gumption to proceed.

“So, indeed,” he began, “back in the late ’90s, 1998 or 1999, Jeanine and I were visiting New York, and one afternoon we went rummaging through the Chelsea Flea Market—I was already an avid collector of old photos and ephemera and the like—and at one stand, we came upon this ancient, dog-eared scrapbook, very much the sort of thing I like to collect, which we bought for $60 … A few weeks later, back home, I picked it up again and really started studying the thing. And I was suddenly arrested by one photo in particular, a sort of theatrical cabinet card with this loopily melodramatic image on the front, and I started wondering where it might have come from. But there was no credit on the back.

“I was about to give up when a blank page fell out of the scrapbook, or a seemingly blank one anyway, because when I held it up to the light, it turned out to be the kind of paper that they sometimes used for interleaves to protect steel engravings, and indeed I could just make out a faint afterimage, presumably imparted by just such an engraving, and it seemed to be saying—granted, in reverse—‘Pearl Street,’ and then also ‘Zohar Studios.’ Or anyway, that’s what I thought it said. I wasn’t sure. But I leaped to the conclusion—you know, one of those two-plus-two leaps that may or may not add up to four—that the cabinet-card photo had been taken at Zohar Studios, and I began to fantasize about the place, I mean, weird name and all.

“And the next time I was back in New York, I dropped by the Argosy Book Store, on East 59th, and you know how upstairs they have those bins of old photo engravings, often arranged by neighborhood. I knew how Pearl Street would have been in the Jewish district on the Lower East Side, so I started rifling through the bins devoted to that general area, and sure enough I found the engraving in question, Pearl Street with the ‘Zohar Studios: Photographs’ banner off to the side, and now I could even make out the street number, which was 432. I bought the engraving and rushed down to Pearl Street, hoping against hope, but of course the building had vanished, along with its address, replaced by a busy intersection. So that gambit proved useless.

“But on subsequent trips, Jeanine and I continued to investigate the mystery—at the library, we tracked down street digests from the time, and that’s how we found out about the photographer’s first name, which was Shimmel, and at another point we got lucky and even found his signature on the register of immigrants arriving from Bremen on the SS Agnes at Castle Garden, where they used to process people before Ellis Island, back on May 2, 1857—here, you can see it on this photocopy.” He handed it to me.

“That’s Zohar’s actual signature!?”

“Yeah, or somebody else signing his name, I suppose. But no, that’s Shimmel.

“And one day we happened into Elli Buk’s antiques emporium down on Spring Street, in Soho, a marvelous place that I often tried to visit on my trips east. And in the back of his store—and this was a really amazing coincidence—I came upon a battered old trunk, and on its side was a label with the name Shimmel Zohar scrawled across it. And after a whole lot of back-and-forth—it wouldn’t have been Buk’s place without that—eventually Buk let me buy it, and a few weeks later, he shipped the trunk here to Pasadena. When it arrived, I tore into it, but alas there was nothing inside, and frankly the thing was kind of rank and musty. So we left it outside to air out.

“And the next morning there was a baby possum inside.”

A baby possum?

“Yeah, it must have climbed in during the night, and it had spent the night scratching away at the bottom of the trunk, probably trying to escape, but in the process, it had revealed a false bottom. And now, after we freed the possum and began further pulling away the false bottom—”

“No!” I interjected. “Really? You found Zohar’s glass plates?”

“Oh no,” Berkman said. “Of course not. They’d have been way too heavy, and probably would have been broken into a million shards in transit. But I did discover a notebook, a big, thick ledger sort of thing, which consisted of a handwritten diary. Unfortunately, all in Yiddish.

“So what to do? My grandparents were no longer alive, so I couldn’t consult them, but I remembered about my old friend Feivel—Feivel Finkel, this grizzled old fellow, a bit of a lush, I suppose, whom I’d once met at Gorky’s, that bohemian dive downtown, during a klezmer-trio performance. He reminded me of a character from Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story “A Friend of Kafka,” because he had this intriguing old-world style of speaking and comporting himself that, granted, may have been something of an affectation.

“Anyway, I tracked Feivel down and told him the whole story about Zohar Studios and the trunk and asked him if he could have a crack at translating the diaries, and he agreed to. And he started dropping off snatches, and the thing turned out to be Zohar’s own ledger of his professional activities, with detailed descriptions of various tableaus he had meticulously staged and photographed, really bizarre sorts of things—talk about unbelievable. Some of our mutual friends cautioned me about how Feivel was really more of a fabulist than a translator, so at a certain point, I tried to get the notebook back, but he kept coming up with all these suspicious excuses about why he couldn’t bring it over. Meanwhile, though, he’d keep calling, and when I came home from teaching or whatever, there would be these long, woozy messages on the answering machine. I kept the tapes, and he’d be describing yet further tableaus.

“And then, sometime in the early aughts, one day he just up and died, which I only found out about a few days later. I rushed over to his apartment to try to retrieve the notebook, but it was too late—the place had already been cleaned out, with everything left out on the curb for the garbagemen to pick up, which they had, and that was that. I never saw the notebook again.

“Of course, I was devastated, I obsessed about the loss for months, and meanwhile, I kept poring over sales and auction catalogs, hoping that some of Zohar’s images might turn up, but they never did. And somewhere in there, I convinced myself that still, somehow, Zohar’s achievement deserved to be memorialized and honored. And so I decided to restage the tableaus myself, as Feivel had described them—as a sort of tribute to Zohar Studios.

“So yeah,” he concluded, sheepishly, “technically, the photos are actually mine. But we really don’t need to make a big thing out of that. As I say, I myself don’t want to get in the way.”

VI.

As Berkman was coming to the end of his saga, his life partner Jeanine wandered in and, leaning against one of the cluttered tables, she smiled at him and then over at me, with an expression that seemed to say, “There, at long last! That wasn’t so hard, was it?”

“Not that it was easy,” Berkman resumed, as if in response. “The project ended up taking a lot longer than I at first thought it would. It spanned four presidents, two wars, and 1,600 pardons, but I don’t feel guilty in the least. I was doing exactly what I wanted to be doing, and verisimilitude takes time.”

“Each of those photos,” Jeanine said, “was like an entire short-film shoot. The treatment, the script, the casting, the costumes, the makeup, the backdrop, the lighting—sometimes it could take months of preparation for a single shot. And it was all happening here in our backyard.”

“Yeah,” Berkman said, “sometimes we’d say we had our very own Cecil B. DeMille Studio going on back here. And things could really get drawn out.

“For example, the people in these Zohar recreations of mine—hardly any of them were friends. Rather, I’d have a vision of the sort of thing I needed, but then I’d spend weeks looking for people who might fit the vision. The three Q’s is how I used to describe my aesthetic: Quixotic, Quotidian, and Quasimodo.”

Quasimodo?

“Well, yeah. The opposite of conventionally attractive. Kind of exiled, setoff, suspect …”

Outsiders? The Community of the Refused?

“Yeah, and when I’d see people like that—the thing is, I’m basically a shy person, it was always really hard for me to just go up to them and ask if they would be willing to sit for me, to take part in these daylong stagings. But maybe that’s where the bushy sideburns came in useful. They gave me a sort of authority, I suppose. I mean they conveyed seriousness …”

Seriousness?

“Well, commitment, anyway, that this wasn’t just some sort of lark. That I was seriously committed to the project. It didn’t always work. I mean, one time over at Skylight Books, I came upon the single best face I ever saw, and I went up to the guy—we got into this really amazing conversation; he was very profound, kind of a mystic, and he zeroed all his energy in on me. We went at it for a long time, and eventually I asked him if he’d be willing to sit for one of my pictures, and he said he couldn’t possibly, and I asked why ever not, and he said it was because he was invisible! I tried to assure him that that might not prove an insurmountable obstacle, but he still demurred.”

I laughed, and found myself asking Berkman about the humor in the images. Had Zohar himself been so humorous, so witty, or was that him, Berkman? For example, who came up with the titles The Downtrodden Banana and the like? Were those his or Zohar’s?

“That’s a good question,” Berkman said. “I’ll have to think about that.”

I sensed we might be about to slide back into the vertiginous sublime all over again, so I decided to steer the conversation elsewhere—to the commentaries in the catalog. Most didn’t address the specifics of the images themselves at all. Taken together, though, they provided an astonishing breadth of insight into the 19th century.

“But again,” Berkman insisted, “that wasn’t me. I’d have loved to provide such a commentary, but we were running out of time. There was no way I was going to be able to do so. So I contacted the Professor.”

Oh, right, the Professor. I asked him to remind me about the Professor.

“Professor M. De Leon. He referred to himself as an itinerant scholar of 19th-century cultural history, and he was the conservator of a distinguished private collection. He wasn’t at liberty to say whose collection, but they seemed to have deep pockets. He traveled a lot for work.

“Anyway, we were good friends, or at least fine acquaintances. I’d been keeping him apprised of developments following my Zohar discovery, and after Feivel died suddenly, I’d been left to pick up the pieces of the project, and as the years passed, it was just proving too much. My life was moving toward entropy, my fountain pen was leaking, my pocket watch was running late, and all the doorknobs in my studio were broken. I was clearly in over my head just with restaging the photographs. I wasn’t sure I’d ever be able to finish them, so a few years back, I contacted De Leon and asked whether he might be willing to take on the commentary, and he was game. And he came to see Zohar as a minor part of the story. To him, the photography took precedence. Most people like to focus on the artist, but he wanted to focus on the art.”

Or anyway, on the century as a whole, I suggested. In any case, he sounded like a fascinating fellow. I asked Berkman whether there was any chance I could call on him.

“How I wish!” he replied, pausing. “But I’m afraid that won’t be possible. He died just a few months ago. So sad. He’d finished his contribution to the book just a few months before that. But yeah, now the volume will be serving as a kind of tribute to both Zohar and De Leon. Too bad, though—you really would have liked him.”

I was sure I would have. I liked his turn of mind. Almost as much as I liked Berkman’s.

I looked at my watch and was surprised to see how time had flown. I had a plane to catch. As Stephen walked me through the clutter of his backyard, he took to musing about Bob Dylan, among other Kabbalists, in a long, convoluted analogy about their respective processes, but then he abruptly shifted musical tropes: “Actually, I sometimes find myself thinking of this whole project, rather, as Chopin played on a kazoo.”

When we reached my car, I turned to congratulate him on the completion of his work. I told him it must be a great feeling. He smiled, correcting me. “It’s been a great privilege,” he said. “It’s not every day you get the opportunity to make history.”

Another great alternate title.

VII.

So that’s all I’ve got—and yes, I realize that it doesn’t entirely hang together. Sometimes things are like that, and what are you going to do?

Oh, except for this! On my way out of Pasadena and back to LAX, I dropped by the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City—don’t get me started—to visit with the museum’s founder, a mutual friend of Berkman’s and mine, David Wilson. (When I told David that I’d been in town at the instigation of San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum to compose some sort of contextualizing piece on their upcoming show of Berkman’s Zohar project, he responded, “Oh, thank God.”) As some may know, the Museum of Jurassic Technology includes within its precincts a Napoleonic Library (again, long story, not now), upon whose pell-mell shelves I happened to locate a copy of Gershom Scholem’s magisterial Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, which I remembered fondly from my own college days. I asked David whether I could borrow the volume for my plane ride back to New York, and he graciously agreed (as long as I sent it back, which I have in the meantime done).

This was how, a few hours later, absorbed in the book, I came upon Scholem’s account of his insanely erudite philological investigations into the actual authorship of the volume that is perhaps Kabbalah’s foundational document, the Sefer Ha-Zohar, the “Book of Splendor,” commonly known as The Zohar. The book presents itself as the product of the eminent second-century Mishnah teacher Simeon ben Yohai’s 13 years of intensive Torah study while hiding from the Romans after the destruction of the Temple—holed up deep inside a Palestinian cave. But Scholem, across more than 50 pages of tiny print based on his own burrowings into archives scattered all around the world, unfurls definitive proof that the book must in fact have been the work of an obscure late-13th-century Spanish rabbi from the Castilian village of Guadalajara.

A rabbi whose name was Moses de León.

So go figure.

Adapted from the afterword to Predicting the Past, the catalog of the Shimmel Zohar retrospective at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco, whose opening, long COVID-delayed, may finally be coming any day now. Or (somehow appropriately) maybe not.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community