For The Atlantic’s October issue, Hannah Giorgis presents the definitive look at Black representation behind the camera

“Since its invention, television has shaped this country’s self-image. To the extent that we share notions of ‘normal,’ ‘acceptable,’ ‘funny,’ ‘wrong,’ and even ‘American,’ television has helped define them. For decades, Black writers were shut out of the rooms in which those notions were scripted, and even today, they must navigate a set of implicit rules established by white executives––all while fighting for the power to write rules of their own.”

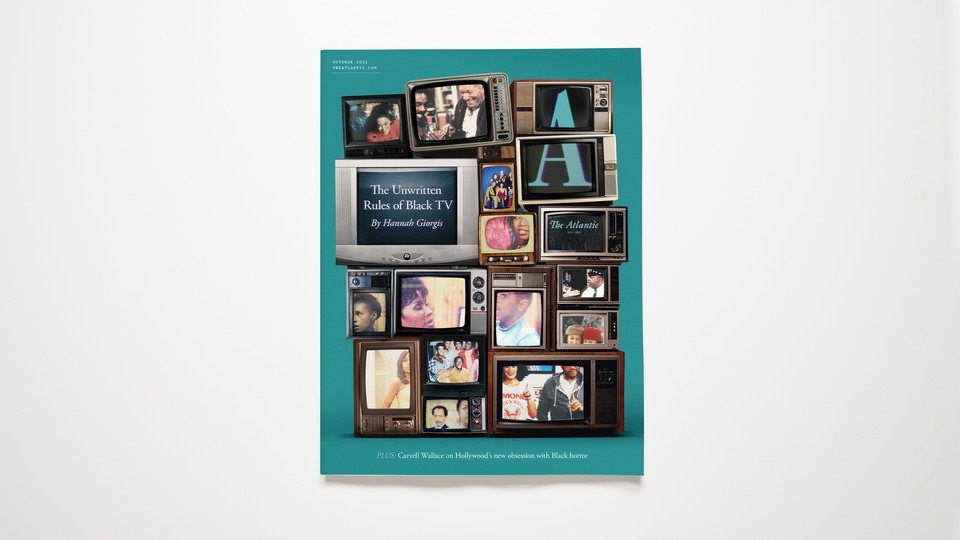

For the cover of The Atlantic’s October issue, staff writer Hannah Giorgis reports on “The Unwritten Rules of Black TV,” presenting a definitive look at Black representation behind the camera, and the progress and roadblocks for creators whose voices have too long been ignored. With access to the writers, producers, and showrunners who have shaped Black TV over decades, Giorgis details the struggle Black creators have endured to deliver shows that feel authentic and relatable to Black viewers, even as many of these shows were overseen by white executives who sought to make them more “appealing” for a wider audience. Hannah Giorgis will discuss the cover story in a conversation on Tuesday, September 28, at 10 a.m. ET as part of The Atlantic Festival.

Giorgis uses a historical lens to trace the evolution of Black television––from NBC’s groundbreaking sitcom Julia to Shonda Rhimes’s record-smashing How to Get Away With Murder––and to contextualize the ongoing discussions around representation. Through conversations with influential figures such as Issa Rae, Lena Waithe, longtime producer Susan Fales-Hill, and Sanford and Sons and The Jeffersons creator Norman Lear, now 99 years old, she illuminates how creators have challenged the industry assumption that white audiences wouldn’t watch shows about Black characters. In an interview, Lear recalled the significance of taping Sanford and Son, a series that debuted in 1972 and regularly addressed the racism its characters faced, in front of a live audience. “There’s no experience like standing behind an audience composed like that––half Black, or half Black and brown, but all kinds of people––and watching them laugh hard, like belly laugh,” he told Giorgis. “I’m very confident that added time to my life.”

When Family Matters premiered in 1989, portraying the day-to-day life of a middle-class Black household, Giorgis writes that the sitcom struggled to become a champion of diversity with a writers’ room that was mostly white. The flaws are evident when reflecting on scenes that aimed to depict what it is like to live in Black America. When a teenage character has an unprovoked run-in with the police, his father’s skeptical reaction to his son’s disturbing experience borders on dismissal and incredulity. It’s a response that writer Felicia D. Henderson tells Giorgis was devoid of credibility for a Black parent. Shortly after the 2020 killing of George Floyd, the Family Matters cast reunited to look back at the episode to examine the relevance of the story line, but also consider where it fell short. The episode is just one of the many examples Giorgis points to in order to illustrate the problem: For far too long, Black creatives have had to “negotiate” with white superiors to produce story lines that portrayed Blackness in a way that was deemed acceptable to white audiences.

So can a new generation change what we see on TV? Giorgis reports on the current state of the industry, in which Black writers and producers are shifting away from ratings-centric network television and heading to streaming services. And yet, they often still hit the same walls. When Issa Rae was first approached about turning her YouTube series into a TV show, she found herself “deathly afraid of losing an opportunity by being too authentic”––too much the person she actually was. In the end, Rae was able to amass enough influence to portray fully formed characters on HBO’s Insecure, a show that, Giorgis writes, “accomplished the rare feat of being a series that depicts Black life without pathologizing or feeling burdened by it.”

Ultimately, for progress and changes in the industry to last, Giorgis argues, “executives and other industry power brokers need to continue investing in creative visions that don’t match their own. They’ll have to cede the terms of ‘authenticity,’ and any negotiations over it, to the Black creators whose voices have too long been ignored.”

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community