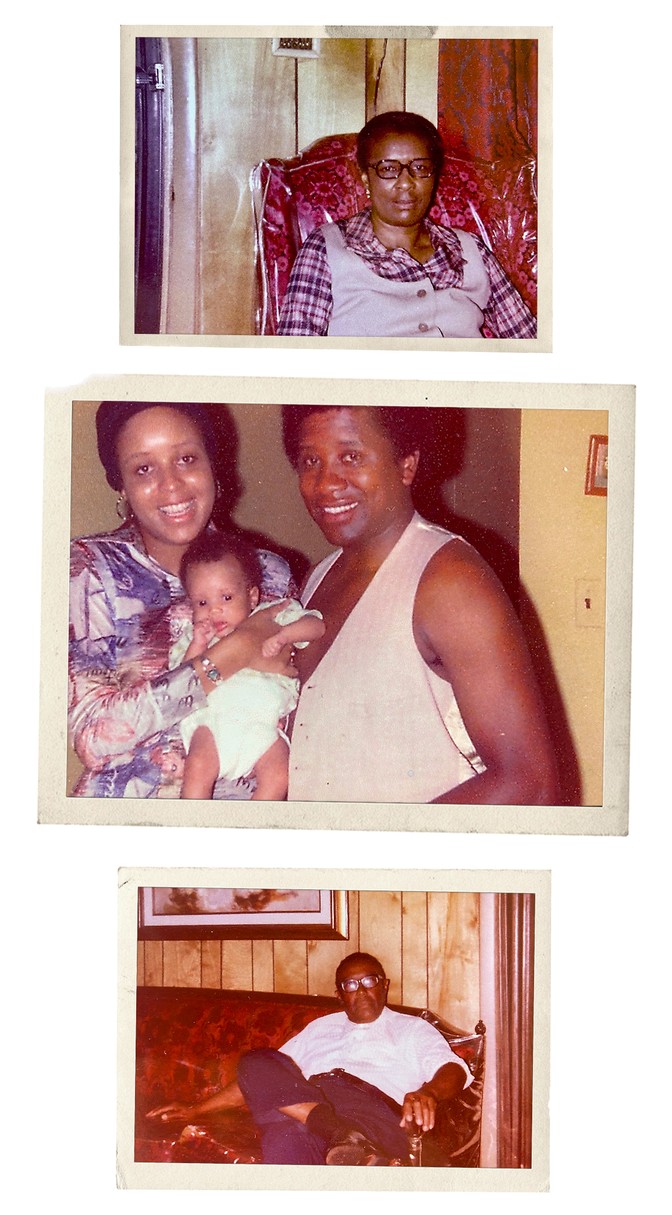

As I slouched cross-legged on the variegated shag carpet in their Memphis bungalow, Grandma—a tall, lean, reddish-brown woman in her 70s—sat languid and elegant on a tufted gold velvet armchair, its plastic upholstery cover crinkling beneath her when she shifted. A few feet away, Granddaddy, a round man in his 80s with horn-rimmed glasses resting on his dark bronze face, perched on a red velvet damask armchair, also covered in plastic. They gazed at nothing in particular—nothing visible to me, anyway—while I formed my questions: What were the names of the Mississippi Delta towns where they were born? What were the names of their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents? What were the oldest tales they could recall?

They answered in turn, hesitantly at first, noting dates and surnames, mentioning towns, states, and even another country, Cuba, through which Granddaddy’s ancestors passed before landing in the American South. I scribbled notes in pencil on a scrap of newspaper, the only paper I had handy.

This would be our only interview, extracting mostly biographical particulars. I took home the scrap of paper bearing my notes and put it in a desk drawer, where it lay for years among a jumble of trinkets and ephemera before disappearing in the whirlwind of packing for college. Over the course of my burgeoning adulthood, I gradually became aware of its loss, my heart dropping when something triggered a memory that took me back to its precious details. Never again, I swore, would I fail as the custodian of a fragment of history.

But I did fail again—this time with my father, whose stories I ceded to the forgetfulness of time until I was well into adulthood. Like my grandparents, he is from Jim Crow Mississippi, and though he was born a generation later—in 1944—little had changed with regard to racial oppression. In 1968, before I was born, he was a Memphis police officer whose undercover work brought him to the Lorraine Motel minutes before an assassin’s bullet struck Martin Luther King Jr. A well-known photograph captured my father kneeling over King while attempting to render first aid, as three people standing nearby point in the direction from which the shot came.

I grew up knowing little of these events beyond my father’s presence in the photograph; he never discussed them, and the rest of my family barely mentioned them. Over time, I’d discover conspiracy theories about his appearance at the scene of King’s murder.

Read: The last march of Martin Luther King Jr.

I used to attribute my reluctance to explore his past to my fear of discovering any truth to the conspiracy theories. But underlying that was a more fundamental fear, prefigured by my grandparents’ reticence and my lost notes: that of the certain horror and grief I’d have to engage with, regardless of the specifics I uncovered. Avoiding my father’s story hadn’t shielded me from the anguish I dreaded, which already inhabited me in some hidden place near the edge of perception. Rather, it merely allowed more history to be lost. And lost history, I came to understand, was far more than a personal concern—it represented a danger to the hard-won gains my forebears and so many like them had made against racial apartheid and atrocities.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community