The varsity dormitory at Harrisburg University is still under construction. A pile of cardboard debris twists around the base of the stairs; the hallway lights beam an industrial, apricot glow; and when 22-year-old Alex Carrell meets me at the entrance and leads me to his room, we have to dodge the contractors installing carpet on their hands and knees. The wooden doors flanking the hallway are each marked with a nameplate listing the inhabitants inside, punctuated by an angry-looking crimson cyclone holding lightning bolts in its Mickey Mouse–gloved hands—Harrisburg’s mascot, the Storm. On his sign, Carrell has written “Saltman”—the alias he uses to compete in a video game called Hearthstone.

Carrell’s bedroom is cluttered with boy paraphernalia—an electric guitar submerged in laundry, a snowboard, a plastic tub of whey protein, a wide selection of “G Fuel” (read: Gamer Fuel) products, a closet full of Harrisburg-branded gear. He’s tall, with a black beanie pulled tight around cursive brown hair and a sanguine letterman confidence that matches the jersey on his back. If this were any other school, he could probably pass for an athlete. And, broadly speaking, he is. E-sports, the business of competing in video games professionally, is projected to top $1 billion in revenue by the end of this year. Carrell is one of the students building the industry’s corresponding collegiate scene—playing Hearthstone in Harrisburg colors, with all the fanfare of March Madness’s Elite Eight. He and his teammates are the only student athletes on campus.

Carrell arrived at Harrisburg last year after being poached from his previous school, Central Washington University. He had already two years there, but when he saw a Reddit post from a new school offering full-ride scholarships for e-sports players, the opportunity seemed too good to pass up.

The application was unlike any other Carrell had written. First, he had to provide proof that he wasn’t faking his high-ranking results in Hearthstone, a digital one-on-one card game similar to Magic: The Gathering, published by the gaming mega-corp Blizzard Entertainment. That was followed by an online tournament tryout, which led to Harrisburg flying Carrell to Pennsylvania for an interview and in-person scrimmage. The school valued Carrell’s skills in the low six figures—he was offered a spot on the Storm roster, single-handedly eliminating all his future debt in the name of video games.

Carrell had been taking out loans before. “I was taking out $24,000 to $25,000 a year,” he told me. “By the time I graduated, I’d be over $100,000 in debt.”

Today, Carrell owes only the $40,000 or so leftover from his time at Central Washington. The rest of his tuition, and his room and board, are covered, so long as he proudly wears the Harrisburg red and yellow in official collegiate Hearthstone competitions. Harrisburg is one of the 128 colleges that fund a varsity e-sports program, and within that, Carrell is one of the very few recipients of a full athletic scholarship for competitive gaming, which is something he says he didn’t know existed until he had one of his own. Carrell doesn’t chalk up his success to blood, sweat, or tears. As far as he’s concerned, he was just in the right place at the right time—a particularly talented gamer, who happened to come of age during the first moment in history when a college might reward that ability with a free degree.

“I saw it and I jumped on it,” he says. “I was like, ‘This isn’t anything that’s happened before.’”

The day after we meet, Carrell and his teammates will compete at the Harrisburg University Esports Invitational—a massive, multi-day collegiate gaming tournament organized by the college—against teams fielded by rivals such as Penn State and Georgia Tech. Compared with those institutions, Harrisburg is almost imperceptibly tiny. The total student population is about 750, the school opened in 2001, and the e-sports program was founded in 2018. But the Storm, and Carrell, entered the weekend as one of the favorites. In the spring, Harrisburg went 33–0 in the Overwatch varsity league en route to capturing the National Championship, streamed live on ESPN. It was their first season together as a team.

Harrisburg University doesn’t have a campus. The school is consolidated in a single gray building in the heart of the city’s modest, ambiently colonial downtown area. It calls itself a STEM college—offering a limited suite of degrees in computer programming, data science, and biology—and walking through its giant glass doors feels a lot more like going to work than going to school. The fanatical e-sports endeavor is, by far, the most noteworthy thing the university has ever done.

Currently, 26 student athletes are enrolled at Harrisburg, playing League of Legends, Overwatch, and Hearthstone. They have full scholarships, and were recruited from all over the world. The program keeps a high-profile coaching staff full of former competitive players, at the top of which is a de facto athletic director, Chad Smeltz, a Harrisburg native who made his name as a League of Legends e-sports personality and coach. Before he was a famous gamer, Smeltz was a high-school history teacher, and regards his return to academia, and to Pennsylvania, as a homecoming. “Usually people go from collegiate to the pros; I’m going from the pros to collegiate,” he says. “The pro scene is a lot about winning and competition, but there’s a lot more I can do in collegiate because there’s a lot more outreach, for building jobs in the e-sports industry, for building educational programs around e-sports … Very few schools have anything close to that.”

E-sports scholarships are still rare, but the idea is quickly becoming normalized in American higher education. Major universities with considerable overhead have started devoting a corner of their scholastic budget to competitive gaming, as a way to both juice scholastic recruitment and future-proof their sports programs for a world where more people are watching Twitch than CNN or MSNBC. Today, the average salary for a League of Legends professional is about $300,000, and professionals in Counter-Strike play for $1 million prize pools several times a year. High-profile colleges are vying to compete, with lucrative incentive packages. The University of Utah hands out $1,000 a year to each of the players participating in its e-sports curriculum. UC Irvine distributes up to $6,000 to its varsity rosters, and $1,000 to its junior-varsity rosters. New York University partnered with the fighting-game-tournament organizer Evo to pay the entire tuition of a lucky fan who wants to transmute his or her e-sports knowledge into a game-design career.

But schools like Harrisburg are playing an entirely different game: They’re willing to treat college e-sports like Alabama treats college football. The hope is that the scholarship money the institution invests will elevate the campus as a dominant force in a still-nascent community. To the school’s brass, that’s a better use of resources than any advertising blitz. “We’re a tiny school. Nobody knew who we were as of a year ago,” Smeltz explains. “The fact that we’ve been able to do all this in e-sports—we’ve been on ESPN’s main channel, for example. How many marketing dollars would that cost?”

One of Harrisburg’s rivals is St. Louis’s Maryville University, also tiny, which holds the honor of being one of the six founding members of the National Association of Collegiate Esports. The traditional logic of college athletics dictates that gigantic campuses, with their long traditions and devoted fans, have a perennial advantage over smaller players. In e-sports, at least for now, that logic is flipped. Harrisburg University has taken the throne, primarily because it doesn’t have much to lose.

“We don’t have anything splitting our attention,” says Eric Darr, the president of Harrisburg University. “Thousands of people go to those bigger schools for football. If someone wanders into the president’s office and says, ‘Hey, I got an idea: e-sports,’ they’d say, ‘What are you, crazy? We’re on national TV this week.’”

The night before the invitational, members of the League of Legends and Overwatch teams are sitting at the rows of PCs that seem to stretch out in every direction in the Storm’s practice facility, logging a few more scrimmages before while they can. The Overwatch National Championship trophy sits on a black table in the middle of the room, amid the arcade cabinets, snack food, stickers, Lego creations, and controllers. In the corner is a banner for the Philadelphia Fusion, a professional Overwatch team based in Pennsylvania, and co-owned by the 76ers.

Titus Bang, a diminutive 22-year-old League of Legends player with rectangular glasses that seem to take up more than half of his face, says his academic schedule is divided into “scrim blocks”—mandated practice—meaning that he’s in this facility every weekday, playing at least three games of League with his teammates. In a past life, Bang was a musical-theater major at the University of Central Florida, but like Carrell, he was seduced by Harrisburg’s promise of free tuition and the chance to play e-sports competitively. In particular, Bang has followed Chad Smeltz’s career since he was in middle school, so the opportunity to play for him in an amateur capacity was a dream come true. “I said, ‘Mom, Dad, what if I got a full ride to play League?’” he remembers. “They said, ‘Get it first, and then we’ll talk.’”

Bang moved to Harrisburg last fall, which effectively erased all the work he had previously committed to his scholastic career. “I’m starting over as a freshman,” he says. “The only credits I had were in ballet, singing, and acting. Those don’t transfer.” Bang tells me that a pivot to something more professionally sturdy, like science or math, was something he had considered for a while after the economic anxiety of being an art major settled in. Collegiate e-sports was the exact miracle he needed.

Bang has been a great League of Legends player for most of his life. In high school, he routinely hit Masters ranks, which is similar to being a Double-A baseball player. So it is at least a little curious that he decided to take his talents to Harrisburg. E-sports does not have the same structure as traditional sports. There is no college draft to participate in the League of Legends Championship Series, the North American club system for full-time League of Legends pros. In fact, the minimum age to join a roster is only 17, and some of the best players in the world get their start in the amateur competitive scene much earlier than that. If Bang wanted, he could drop out of school now and direct his efforts and talents toward the pursuit of a professional contract.

This is something that Bang thinks about a lot. E-sports offers the long odds of any professional athletic career, sieved through the potential for risk and poor management inherent to an upstart industry. Last year, the professional league for the video game H1Z1 was canceled halfway through its first season. The players involved spent months trying to track down the paystubs they were owed. Heroes of the Storm was similarly nurtured, with a fully funded league since 2016—until its publisher suddenly abandoned ship, leaving an entire conference of players out of work and twisting in the wind.

The market for players of the games that Harrisburg sponsors—League of Legends, Hearthstone, and Overwatch—is relatively healthy, but it’s still an unstable profession. Kevin “Hauntzer” Yarnell is one of the greatest American League of Legends players of all time, and yet he’s played on six different teams in his six-year career due to constant roster shake-ups. The best-case scenario for a pro gamer still involves a lot of entropy, so for now, Bang intends to keep his options open. A marriage to e-sports is at its happiest and healthiest with a prenuptial agreement.

“A hundred people try [to go pro] every year, and only one or two make it,” he explains. “If you’re an amateur, what happens is you’ll do that for a year. You do it again. Or you’ll make it as a pro, and you’re dropped back down to amateur. You have nothing to show for it. I feel like here, [at Harrisburg] it’s a lot more stable. I feel like I can improve on my game, while earning a degree.”

Bang isn’t ruling out a run at the professional scene. He says he will be cordial to any team that may approach him after his time at Harrisburg is complete. But more important, he has the “peace of mind” that wherever gaming takes him, a civilian life will still be within reach. “Even if it doesn’t work out for me, I’ll have things that I love,” he says. “[A degree] gives me so much agency in my life.” For now, Bang is appreciating the perks of being a college athlete. Harrisburg has equipped him with a personal trainer and a diet plan to keep his mind sharp during long practice hours. The varsity dormitory is warm and perpetually unlocked, a nice place for a hopeful e-sports star to spend his time savoring the one moment in life he’s guaranteed to enjoy being a competitive gamer without worrying about how that vocation intends to pay him back.

“Yesterday I was in one of the Overwatch player’s rooms, just watching him play all night,” says Bang. “I never thought [I’d be a varsity athlete] in my life. I never thought that. It’s a bit surreal.”

In total, 30 schools make the trip to Southern Pennsylvania for the Harrisburg Invitational—an odd blend of academic and athletic imperiums like Penn State and Ohio State, and teensy private no-names like Aquinas College, Lackawanna University, and Averett University. Harrisburg, as the flag-bearer for the event and one of the gilded establishment powers of amateur e-sports, is fielding two teams in Overwatch, and two teams in League of Legends. The bracket is structured in a way that could lead to a Harrisburg vs. Harrisburg final, which would be about as exhilarating for the school as it would be disheartening for the collegiate e-sports confederacy as a whole. Today is the group stages; varsity teams are seeded against one another to determine who will play in the marquee knockout round, which will be broadcasted live on Twitch.

For now, though, group play is consolidated in a series of lecture halls outfitted with series of obsidian computer rigs, back-to-back, linked together by a LAN cable. The walls are coated with whiteboards on which event officials have written the day’s schedule, in the same way a professor might scribble down chemistry notation. The 12th floor holds a banquet table stocked with aluminum-tray catering and pallets of Coca-Cola. This is where the student athletes marinate between matches.

The mood in the building feels more like a collegiate track meet than a pageant for competitive gaming. Unlike many other e-sports tournaments, which are built for spectators, the invitational is not a consumer-friendly event. The League of Legends room contains a few chairs, with a pair of TV monitors broadcasting a portion of the action on a delay. There’s nowhere to sit in the Overwatch room, which forces viewers to watch the matches over the players’ shoulders. Hearthstone gets the rawest deal of all: The players are sequestered in an alcove deep down a lonely hallway.

There are no commentators or announcers anywhere, nor is there a centralized itinerary to keep track of the schedule. All you hear is the sound of machine-gun keyboard tapping, and the rapid-fire gamer jargon of teammates warning one another about ambushes, misdirections, and opening gambits. Winners and losers can be identified by the relative glumness on the competitors’ faces, and the only citizen spectators seem to be either well-meaning parents who have made the trip, or the rare diehard superfan. (One person was hoisting a Ragin’ Cajuns flag behind the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s Overwatch team.)

If the University of Harrisburg’s administrators intend to convince nonbelievers of the promise of college e-sports, they are doing so by ditching the fireworks in order to treat the tournament as seriously as possible. This took me by surprise. E-sports, for much of its short life in the public eye, has been a business about excess. DJ Khaled played a bizarre set at the 2018 Overwatch World Championship. The International, the championship series for the video game Dota 2, handed out a $30 million prize pool in August. The Fortnite mega-streamer Tyler “Ninja” Blevins and the masked DJ Marshmello paired to win the Fortnite Celebrity Pro-Am in a Los Angeles stadium last summer. It often feels like the investors behind the e-sports boom are shoveling ludicrous capital into the industry to ensure that it’s too big to fail, but there is little of that comic overkill in Harrisburg. The invitational is built with one directive in mind: college kids competing against one another in video games. Nothing more, and nothing less, presented with the subdued fanfare of a minor PGA Tour stop.

Harrisburg is performing well. I wander into the League room and take a seat among the seasoned players. Next to me is the team from Miami University (in Ohio), and I start talking with Nathan “Lucent” LaMantia, a 19-year-old from Cleveland who’s majoring in marketing and media. Miami Ohio offers a couple of partial scholarships for e-sports, but nothing close to the full rides at Harrisburg. As LaMantia tells it, he often feels like the fix is in.

“It feels good to beat the scholarship teams. You can buy players in [college] e-sports. These are typically smaller universities, small private universities especially. Big universities aren’t throwing all their resources at e-sports like Maryville or Harrisburg would,” he tells me. “It’s hard to compete if you don’t have any form of recruitment, or if you don’t have scholarships. All of us came to Miami for the education it provided,” he says; it so happened to all be good at League.

For generations, Power Five schools have emptied their coffers to attract the best amateur athletes in the country to their campuses with full-ride scholarships, stacking the deck against smaller institutions that don’t have the same resources. The same argument about athletic purity has started to make its way to collegiate e-sports, in a slightly different way. LaMantia and his teammates are one model for what amateur e-sports could look like. Harrisburg is another.

“I have respect for the amount of work [schools like Harrisburg] have put in. All of the players, all of the staff, they’ve put in an extraordinary amount of effort into” their game, LaMantia says. “But in terms of competitiveness? It does start to sway the balance at an event like this.” He notes this isn’t restricted to e-sports. LaMelo Ball famously committed to play basketball for UCLA at the age of 13. But LaMantia says that because so few schools are offering significant scholarships in e-sports, the skills gap on the LAN cable is more pronounced. “It’s very top heavy,” he adds.

LaMantia recognized an ennui I felt the entire time I was in southern Pennsylvania. Here was a dominant collegiate competitive-gaming program, operating in almost total isolation from a scholastic culture, and the town it represents. Harrisburg’s administration saw how remarkably easy it could be to conquer amateur e-sports, and it did so in the simplest way possible—by making offers that nobody could refuse. It worked, but there’s a strange coldness to the program that becomes more apparent the longer you spend in the building. Not once did I meet a self-described Harrisburg fan or alumnus. Perhaps that’s a symptom of the relative youth of the program, but it also served as a reminder that Harrisburg University remains a single nondescript tower across the street from a liquor store. It’s hard to create a sports culture in an arena like that, even with some of the best players in the country.

Follow e-sports long enough, and you start to see the ways that the sector’s speculatory dreams and financial reality blend together. Billionaire investors such as Stan Kroenke have dumped untold capital into competitive gaming with the typical capriciousness of Wall Street hedging. It can be both euphoric and existentially terrifying to consider how quickly that money can disappear. Competitive League of Legends has yet to become profitable for the game’s publisher, which lumps it in with Uber, and Twitter, and dozens of other towering corporations that are both profoundly ubiquitous and perpetually bleeding money. A school deciding to become a collegiate powerhouse, practically overnight, is perhaps the sharpest articulation of that hubris.

On the second morning of the tournament, I catch up with Titus Bang in the practice facility. His League of Legends team had made it through the gauntlet, and Maryville waited in the semifinals. I ask him plainly whether he feels any school spirit—if the investments handed down by the college administration have resonated as part of his identity. He says yes, emphatically. To Bang, Harrisburg offers a total commitment to his talents, one that was willing to pay his rent, buy his food, and construct a training arena in his honor. Here, school spirit isn’t about tradition. There is no tradition. Not yet. Instead, it’s about creating a world where his scholarship isn’t an outlier. Everyone at Harrisburg talks about the future, but Bang is proud to represent the present. There is no greater accomplishment than being one of the first to legitimize the hopes of kids just like him.

“That’s why I want to win the invitational,” he says. “Because it proves that we’re doing so much more.” Only in college e-sports can you be the odds-on favorite, and still a bit of an underdog.

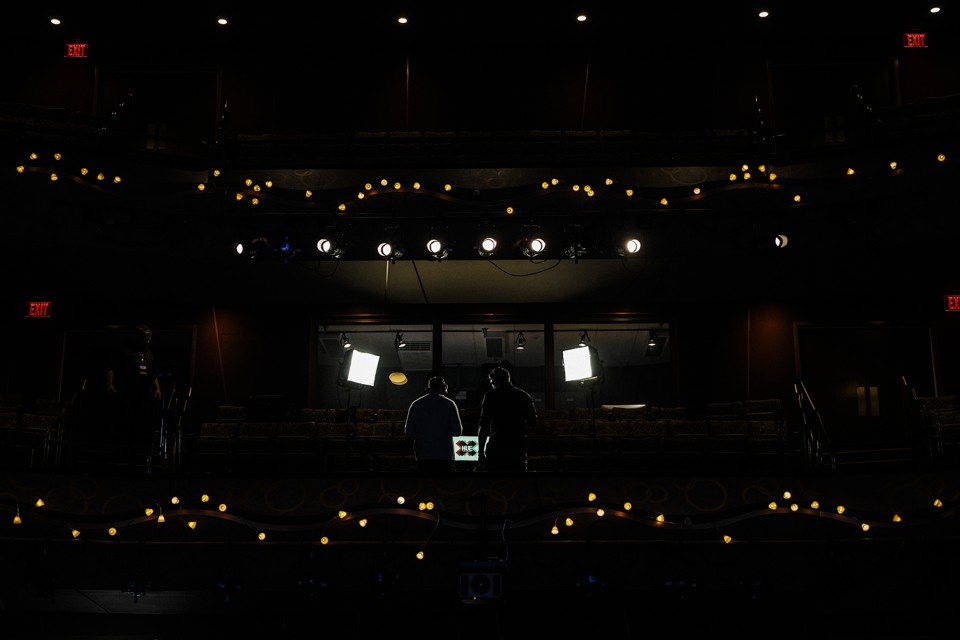

Unlike the lecture hall, Harrisburg’s Whitaker Center is more than capable of hosting an e-sports event. Two sets of computers are mounted onstage beneath an enormous HD display, promising the attendees that they won’t need to invade any personal space to enjoy the games this time around. Harrisburg has hired live broadcasters for Overwatch and League of Legends, and hooked them up to a booming sound system to better contextualize the action for the audience. A simple plastic trophy rests on the stage floor in front of the teams.

Bang isn’t onstage—his team ended up losing to Maryville—but Harrisburg’s other League of Legends team made it through its end of the bracket, so the school still has a chance to win the title. Carrell’s Hearthstone team lost too, due to, in his words, a combination of bad luck and bad play. But he’s still wearing his Storm jersey. In three days, I scarcely see him dressed in anything else.

Around him are the students from other teams who don’t have anywhere else to go after getting eviscerated by the power schools. A countdown on the screen ticks down to zero. The players ready their headsets and triple-check their game plans. And for the first time of the weekend, I hear the Harrisburg faithful cheer their team on.

A few hours later, it’s over. Harrisburg has lost both championship matches, in League of Legends and Overwatch. The Maryville Saints pose for pictures with the trophy, as the rest of the school filters out onto the quiet sidewalk. It’s one of Harrisburg’s first tastes of tribal defeat, the sort of drubbing that’s particularly debilitating when it comes at home, at the hands of a rival. But gut-punch losses have a bewitching quality. Perhaps with a few more of those, Harrisburg will muster the spiritual zeal necessary to give its e-sports program the mysticism it needs. They’re already really good. But in college e-sports, that’s the easiest part of the equation.

Related Video

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community