“Every day’s a good day when you paint.” —Bob Ross (1942–1995)

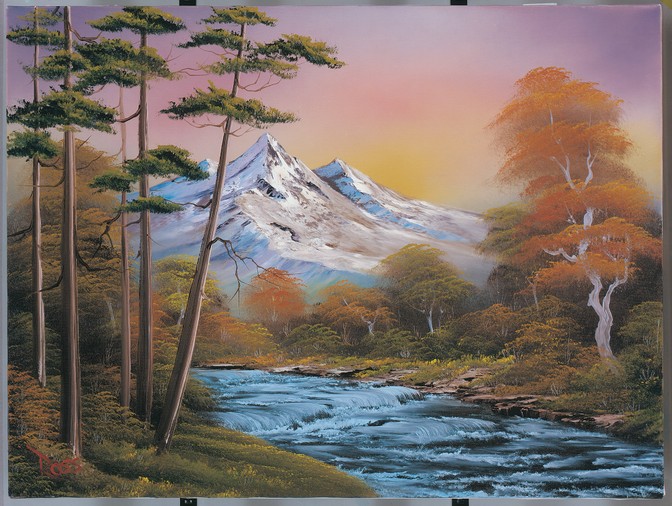

Staring at the empty canvas on the easel in front of me, I couldn’t understand how this—nothing—might somehow transform into even a rough approximation of the Bob Ross painting we were using as a model. That painting was classic Bob Ross: a snowy landscape bursting with color, a world of glimmering trees and vibrant shrubs around a slick icy pond. Gazing at it evoked that feeling you get sitting by a fire on a crisp, cold night. No way I could make anything like that.

I was in a room on the side of a big-box craft store in the suburbs north of Dallas, about to start a class taught by John Fowler, a Bob Ross–certified instructor—which means that he spent three weeks in Florida learning the wet-on-wet painting technique Ross employed on television. A tall, bespectacled man in his 60s, with a light beard and a deep voice and soothing cadence reminiscent of Ross himself, John explained that he has a few things in common with the puffy-haired painter. They both spent many years in the Air Force, for example, and both retired with the rank of master sergeant. I’d learn he also uses some Bob Ross vernacular, sprinkling instructions with expressions like “We don’t make mistakes, we just have happy accidents.”

John watched Bob Ross on The Joy of Painting for years, both during the show’s original run in the 1980s and ’90s, then later by streaming it. Four years ago, John decided to get some paint and a canvas and try painting along with the host. He liked it so much that he took some lessons. Then he liked those so much he paid about $400, not including supplies or lodging, and signed up for the official “Certified Ross Instructor” class, taught by Bob Ross Inc. trainers. When we met, John was wearing a black T-shirt with the painter’s face on it.

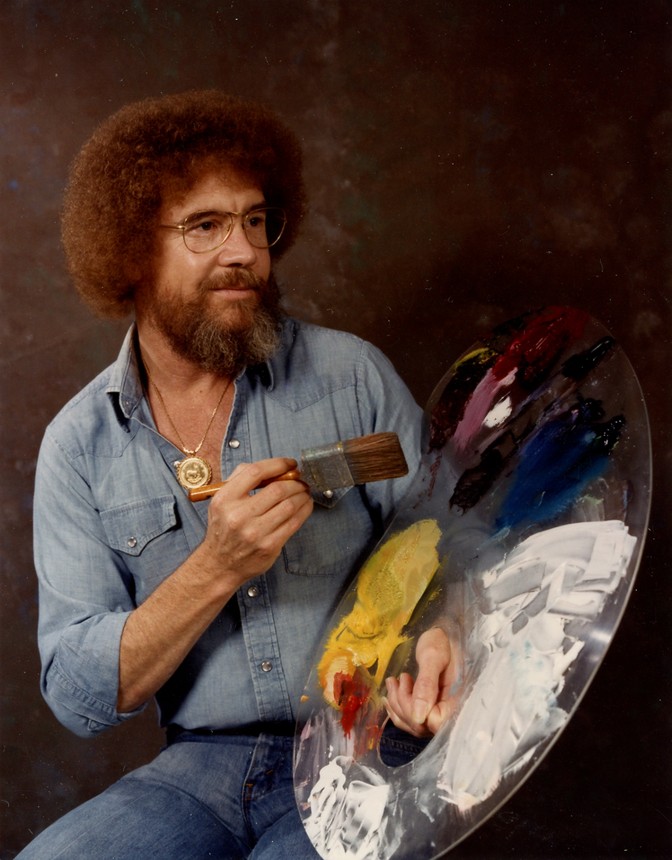

If you’re somehow not familiar with the name, Bob Ross is probably America’s most famous painter. With his distinctive hair, gentle voice, and signature expressions like “happy little trees,” he’s an enduring icon. Even 25 years after his death, he’s popular not only with viewers who remember him fondly, but also with kids who weren’t even born when his show was originally on the air.

Bob Ross Inc. is still thriving. The company owns hundreds of highly sought after Bob Ross originals. (It’s almost impossible to find one of his paintings for sale.) The official Bob Ross YouTube channel, run by the company, has over 4 million subscribers and more than 360 million total views. His likeness appears on a wide assortment of objects: paints and brushes, toasters, socks, calendars, dolls, ornaments, and even a Chia Pet—the plant grows in the shape of his famous hair. There are branded games and Pez dispensers and a children’s book. Every Halloween, thousands of Americans don curly-haired wigs and carry paint palettes and attend parties as Ross. As the coronavirus pandemic has spread and the world has gone inside, tens of millions of people have turned to old Joy of Painting episodes.

Bob Ross is the ultimate calming presence.

I wanted to understand his magical draw. I wanted to understand what it is about this man, and this show, that appeals to so many people across space and time.

That’s how I ended up at the craft store, about to paint a picture for the first time since I was in elementary school. Like John, I’ve watched Bob Ross for years. Unlike John, I’ve never tried painting along. I’ve always been content to watch and listen as the painter whisks out a serene portrait of nature in just under half an hour. But maybe, by actually using his technique, I could learn something else. Maybe by emulating Bob Ross, I could better understand Bob Ross.

Read: Getting through a pandemic with old-fashioned crafts

John laid out nine gobs of paint, each a different color, in a semicircle on some butcher paper next to my easel. This was to be my palette. I recognized the names of the colors from hearing Ross say them on the show: Alizarin Crimson, Van Dyke Brown, Yellow Ochre. John explained how to spread the paint out and tap it onto the end of the brush’s bristles.

Then it came time for the first strokes of paint on the canvas: some bright orange figure-eight marks to represent the sun on what would be the horizon. John demonstrated on his own canvas a few feet away, then I tried my best to mimic what he was doing. Seeing the color slowly spread across my canvas was both exhilarating and terrifying. Mine was also a little clumpy at first.

John must have noticed a skeptical expression on my face, though, because he looked at me and quoted one of the famous painter’s favorite mantras: “You can do it!”

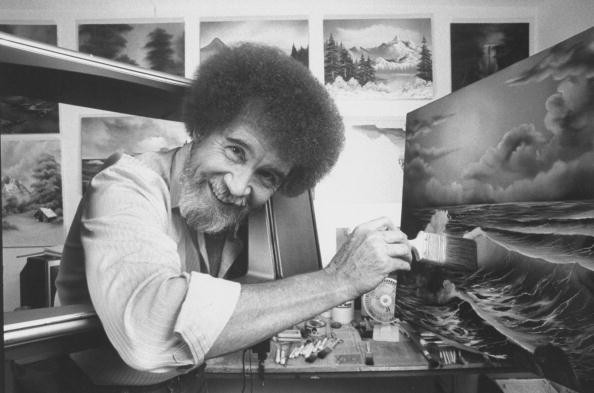

I don’t remember the first time I saw Bob Ross on TV, but I have distinct memories of watching him when I was a kid. If I was flipping through channels, I couldn’t help but stop whenever I saw his signature perm. I was mesmerized by the way he seemed to wave his paintbrush like a wand and create delicate pine trees and majestic mountains. I was hypnotized by the soft scratching sound of the brush hitting the canvas and by his gentle voice—just a smidgen louder than a whisper—narrating each step and encouraging the viewer every chance he got.

In every episode, Ross explained his art not merely as a way of layering paint, but also as a way of capturing the eternal beauty of the world and living free no matter the challenges in life. As he filled his canvas with light and color, he’d say things like “This piece of canvas is your world, and on here you can do anything that your heart desires.” When he painted a cloud, he might say, “A cloud is one of the freest things in nature,” or “Clouds sort of float around and have a good time.” When he’d turn his painter’s knife on its edge and carve out a crisp, snow-capped mountain, he’d sometimes point to one side and say, “This is where the little mountain goat lives, right up in here. He needs a place to call home, too, just like the rest of us.”

The show, which originally ran from 1983 to 1994 and consisted of more than 400 episodes, was as meditative as it was instructive. Ross was a force of pure positivity in a world without a lot of it. Later in life, when writing magazine stories became my full-time job, I started watching old Joy of Painting episodes when I wanted some inspiration. Writing can be a lonely endeavor, and writers are prone to self-doubt. Sometimes when I need a bit of outside encouragement, I turn to my old friend Bob Ross. His calming voice helps me cut through the noise of life and focus on creating something new.

Read: One hundred poems that capture the meaning of joy

It turns out that a lot of other people feel the same way. As long as he’s been on television, he’s had a large, devoted fan base. At the end of the 1980s, Joy of Painting had 80 million worldwide viewers and received 200 letters in the mail every day, according to old newspaper stories. Not long after the show went on the air, the company that Ross started with his business partners created an 800 number fans could call to ask questions about the painting technique: My trees are blurry or My rivers look funny or My colors are mixing when they shouldn’t. Sometimes people would call just to talk about life in general.

As many fans as he had, Ross was never taken seriously by the contemporary art community. Because he was on TV. Because he used the wet-on-wet technique—piling layers of paint on the canvas before any of it dried. Because critics thought his work was frivolous. Because he was everything that he was.

He seemed to be okay with that. On a 1994 episode of The Phil Donahue Show, the host prodded the painter in front of a studio audience.

“Say out loud that your work will never hang in a museum!” Donahue shouted.

“No,” Ross said with a smile. “Well, maybe it will, but probably not the Smithsonian.”

“Why?” Donahue asked.

“This is art for anyone who’s ever wanted to put a dream on canvas,” Ross said. “It’s not traditional art. It’s not fine art. And I don’t try to tell anybody it is.”

He first crossed over into the pop-culture mainstream when he started recording MTV commercials in the early 1990s. At that point, his appeal was a little ironic. But over time, the appreciation of Bob Ross has morphed into something nearly universally earnest. A 2011 PBS documentary, Bob Ross: The Happy Painter, featured interviews with celebrities from a variety of fields who were unabashed fans.

“I used to watch Bob Ross all the time,” Brad Paisley, the country music star, told the camera. “The thing I remember was his positivity.”

“He makes it look incredibly easy,” the actress Jane Seymour said.

“He was an entertainer in his own right,” Phil Donahue said. “Without any flash.”

Even in the comments under the YouTube videos, usually one of the more poisonous forums on the internet, nearly all of the posts are appreciative. Under a video with nearly 30 million views, the top comments run along the lines of “If art teachers were all like Ross, no one would fail, no one would feel ashamed to show their work, no one would dread to come to art class. He is so inspiring!” And: “He didn’t paint to show how good of a painter he was. He painted to show how good of a painter you could be.”

With his 400-plus episodes of The Joy of Painting, Ross spent upward of 200 hours on television. In all that time, though, he revealed very little about his personal life. He said he had the best mother ever. He said his father taught him carpentry. (It’s how he lost a piece of the index finger on his left hand, occasionally visible onscreen in shots of Ross holding his palette.) He introduced viewers to a variety of small animals, often wounded squirrels and birds he’d nursed back to health. He’d sometimes invite his son, Steve, to read viewer mail or to substitute-teach an episode. In general, however, he was a very private man. Part of his appeal, I think, comes from the fact that his complicated personal life never bled into his work. In episode after episode, he remained as inscrutable as the Sphinx.

A lot of what we know about Bob Ross can be surmised from his art. He always painted scenes of nature in its full glory. His landscapes were always full of color, full of trees and mountains and clouds, and teeming with animals. He almost never painted people.

On occasion, he would mention that he grew up in Central Florida—where, he said, he once tried to nurse an injured baby alligator in his family’s bathtub—or that he’d spent 20 years in the Air Force, 12 of which were in Alaska. He fell in love with the snowy mountains that would later feature so prominently in his art. Alaska is also where he learned to paint—and realized quickly that he liked painting much more than he liked being in the Air Force.

“The job requires you to be a mean, tough person,” he once told the Orlando Sentinel. “I was fed up with it. I promised myself that if I ever got away from it, it wasn’t going to be that way anymore.”

In 1975 he had a part-time job as a bartender. One day, the TV was tuned to the public-broadcasting channel, and he saw the art show hosted by the cheery, German-accented television painter Bill Alexander. In a format similar to what The Joy of Painting would become, Alexander would finish an entire painting in under 30 minutes, encouraging the audience the whole time with phrases like “With all of our creative power, we will create a better tomorrow!”

When Ross left the Air Force, he got a job teaching classes all over the country for Bill Alexander’s company. In 1982, he was running a five-day workshop in his home state of Florida when he met Annette and Walt Kowalski. When the Kowalskis’ oldest son died, Walt signed Annette up for a five-day painting class with Alexander. She was disappointed to learn that the German had recently retired and that she was stuck with someone she’d never heard of. When she met Ross on that first day, though, she was transfixed. At the end of that week, the couple invited him to dinner and asked him to quit working for his mentor’s company and go into business with them. They wanted him to teach classes in Virginia, where they lived. He agreed.

They took out ads in the newspaper and he put on public demonstrations, painting in malls. To save money on haircuts, Ross got a perm. Later, he’d complain to people how much he disliked the poofy look—but he knew he couldn’t change it, because his hair was his trademark.

The TV show started in 1983, when he and Annette approached a Virginia public-broadcasting station about recording a commercial for their classes, and the station invited him to record a 13-episode season of shows. There was no money in it, but they knew this was how they could increase demand for the classes. By the second season, which was recorded at a public-television station in Muncie, Indiana, they had the formula down: a black-curtain backdrop, just Ross and his easel in as intimate a setting as possible. It all looked spontaneous, but he always kept a finished version of each episode’s painting just out of frame to use as a guide. He told people that he chose to wear jeans and a simple collared shirt so the show would retain a timeless quality.

From the December 2019 issue: My friend Mister Rogers

Over the next few years, more and more stations picked up the show. More viewers, more classes, more believers. By 1987, Ross was crisscrossing the country, teaching classes nearly year-round. He and Annette established the first group of certified instructors to handle the demand. Each instructor would be trained in both the technique and the calm approach. Within a few years, he was more famous and on far more stations than Bill Alexander had ever been.

Looking back now, it’s easy to see why. A Bob Ross level of positivity is contagious. When someone can conjure that amount of peaceful happiness, it compels other people to pay attention, to partake in the bliss. Each episode also feels complete: What starts out as a few scratches on the canvas soon turns into an elaborate, beautiful glimpse of the world. His message was prescient, too. More than a decade before most therapists were telling clients to be mindful and present, Ross was telling his viewers to appreciate their every breath.

Watch his last recordings, and you can tell that he’s wearing a wig and is more tired than usual. But his spirits were still high. The public didn’t know he was even sick until July 4, 1995, the day he died from lymphoma.

Episodes of his show still air on public television somewhere in the world every day. It’s the most popular painting show in history. As much as he loved oil and canvas, his true resonance is with the screen. To this day, millions of people gaze at the videos he made and feel a deep emotional connection to them. That’s why his popularity only grows.

And his art will hang in the Smithsonian. In July 2019, the Smithsonian’s American History Museum announced that it was adding four Bob Ross paintings, his easel, two of his notebooks, and several fan letters to its permanent collection.

Today, there are more than 3,000 officially sanctioned Bob Ross instructors worldwide. Everyone has their own reasons for following in Ross’s path, but there are a few themes that come up consistently. Instructors I spoke with talked about the contentment that comes from his style of painting. Several mentioned the joy that comes from sharing encouraging messages with their students. To his most diehard fans, it’s no surprise that he’s as popular as he is in 2020.

Now more than ever, we live in a time of anxiety and uncertain futures. Our world is full of conflict. Much of our entertainment is loud, suspenseful, tense. Bob Ross, in all his gentle simplicity, is an antidote to all of that. By creating dream nature escapes on canvas, he gives us a real respite from the ills of modern society.

Read: What Alexander Calder understood about joy

Even Walt and Annette Kowalski, the people who discovered and partnered with him, are sometimes mystified by the long-lasting fascination with all things Bob Ross—though they’re convinced he’d be tickled to see his face on a waffle maker.

“We can’t even explain fully what this Bob Ross thing is,” Walt told The New York Times last year. “I can only go back to that first day that I was in the class with him,” Annette explained. “I feel like the whole world now is seeing what I saw.”

The Kowalskis’ daughter, Joan, is the president of Bob Ross Inc., which is still based in Virginia. The 800 number (1-800-BOB-ROSS) is still active—and still receives the same types of friendly callers they were getting in the ’80s. Most of the time callers get a voicemail promising a prompt response to any questions.

The more I painted the Bob Ross way, the more I see what he’s been talking about all these years. Painting like this, creating something from nothing, is pure. So is a person who embodies positivity to this extent.

At first, I thought my bushes looked too much like tiny multicolored volcanic eruptions. Then I worried that some of my trees looked like awkward smears across the canvas. In all of my years watching Bob Ross, I had never understood exactly how precisely he loads and unloads the brushes, something I didn’t have a feel for at all. If I wrote like I painted, my sentences would look like this: TTHhhiissp is a baddd sentenc. But as the picture filled out with snow and a reflective pond, I could take a few steps back and see how the individual parts added up to a larger image that hadn’t been clear at all when I started.

I certainly made plenty of mistakes—er, happy accidents. But nothing John couldn’t help me blend away or cover with a bush or a tree or a drift of snow. I know it’s no masterpiece, but I’m pretty pleased with the way it turned out. I sort of surprised myself. I sort of want to try it again.

Seeing a painting come together on my canvas reminded me of something. It felt a little like writing a story. At times, it may seem impossible, turning a blank page into something people might actually enjoy. But the first step is believing that you can do it. The only way to get there is to start with a jumble of words and punctuation marks—and to keep building, layer by layer, as you go.

As Bob Ross would say, you might even make something beautiful.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community