Eric Lidji is a man who cares deeply about modest ambitions. He has lived in Pittsburgh on and off for 20 years. It is a city perfectly sized to his sensibility, neither very small nor very large—a place known to but mostly ignored by those who do not live there. Lidji, 36, has held many jobs; most recently, in late 2017, he became the director and only permanent staff member of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives, a repository of early-20th-century local Yiddish-theater posters as well as records from dozens of small-town synagogues in western Pennsylvania. But even before he became an archivist, Lidji’s work has always been the same: He is a diarist of small delights, a chronicler of curios, an ardent psalmist of Pittsburgh’s quirky charms.

Like many of the 49,000 other Jews in the Pittsburgh area, Lidji was socializing at a local synagogue on the final Saturday in October last year when he heard the first rumors of a shooting at the nearby Tree of Life synagogue. The news was soon confirmed: Eleven Jewish worshippers had been murdered. Lidji felt paralyzed: Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest, was still ongoing, and he wasn’t sure what to do. It wasn’t until a few hours later that something clicked, and Lidji felt a certain desperation stirring alongside his sorrow. Already, people were laying artwork and stones, which Jews customarily place on graves, on the sidewalk around the synagogue where the shooting had taken place. Many of the accumulating objects were fragile and homemade, with no clear owner or steward, left outside without protection against Pittsburgh’s notoriously wet weather. This was not just an outpouring of grief, but a proliferation of artifacts—artifacts that, in Lidji’s view, should be preserved.

On the Monday morning after the shooting, Lidji met with half a dozen colleagues who work in other divisions of Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center, where the Jewish archives are housed. Together they formed a task force, fanning out to as many vigils, funerals, and religious services as they could. They filled their bags with copies of programs and approached speakers after public events, asking them for their notes. Whenever Lidji spotted someone carrying a sign, he would hurry over and hand them a business card, hoping they would call him when the card reappeared at the bottom of a purse or in a pocket emptied for laundry and offer to donate what they had made. Sometimes he felt overwhelmed. On the Tuesday after the shooting, he showed up at a protest against President Donald Trump in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh’s historic Jewish neighborhood, to find thousands of people gathered in the streets carrying signs and banners. “It felt like … archiving the ocean,” he told me.

The grim reality of Jewish history is that Lidji is not the first archivist of his kind. Medieval Jews buried family heirlooms in the walls of their houses in times of plague, fearing that they might be blamed for the disease. Scholars founded the Yiddish institute YIVO in the early 20th century, recruiting ordinary Eastern European villagers to collect photographs and folktales of a culture threatened by pogroms and mass migration. Emanuel Ringelblum led a covert effort to collect and bury artifacts documenting life in the Warsaw Ghetto in the early years of the Holocaust, before its inhabitants were murdered and its remaining structures burned to the ground.

Archives neither predict nor prevent atrocities. They document what has happened, but remain neutral about what is to come. Their purpose is to endure as a monument to smallness, a reminder that history is in part a composite of stories about little lives. The purpose of Lidji’s archive is to keep what happened at Tree of Life from being reduced to “Pittsburgh, synagogue shooting, 11 dead,” and nothing more.

Every morning, Lidji rises in the 4 o’clock hour, when it is still dark. He was in the midst of renovations on his house in the Garfield neighborhood when he got the job at the archives, and now lives spartanly in three semi-habitable rooms upstairs. His morning ritual begins with grinding coffee beans from Zeke’s, the shop beloved by locals in East Liberty, the next neighborhood over. Then he puts on a pot of beans and rice or something similar for breakfast. He glances at The New York Times and local Pittsburgh papers to read the headlines and, only a little jokingly, to make sure Jews are still allowed in this country. He finally takes his place at his desk and begins to write.

Lidji started keeping a new kind of diary on October 27: notes about what he’s collected, whom he’s talked to, what the community seems to be feeling. He types quickly, with no poetry or flourish—the goal is to export as much as he can from memory to paper. After a couple of hours, he packs up his things and leaves for the next stop in his day: morning minyan, a gathering of 10 or more Jews for prayer.

[Read: The fight to make meaning out of a massacre]

Since the attack, Lidji has experienced a personal religious transformation: After nearly 15 years of haphazard Jewish observance, he started attending services every day. But there were other reasons to show up for prayer: It has proved a useful venue for winning people over to the cause of archival collection.

Documenting history is often the last task on any community’s mind, all the more so during a time of grief. Prior to the shooting, the archives mainly served as a repository for records from at least three dozen local synagogues, each with its own distinct religious identity or immigrant population; for miscellanea, such as World War II–era correspondence and photographs of big groups at synagogue anniversary dinners and holiday events; and for files from 75 small-town Jewish communities scattered across western Pennsylvania. It holds at least one item from nearly every Jewish organization that has ever existed in Pittsburgh, Lidji told me.

And yet, that work was largely hidden to all but the city’s biggest history buffs. After the attack, Lidji’s first big challenge was becoming more visible to the community: being unobtrusively, insistently present at memorial events, and building relationships with community leaders. His second big challenge was convincing the Pittsburgh Jewish community that its history is worth preserving.

The first time Lidji felt “any sense of accomplishment,” he told me, was when a man who had been “polite but reticent” about the archival project came over during morning minyan one day and announced that he had found “the perfect object.” On the day of the shooting, a boy had been celebrating his bar mitzvah at an Orthodox synagogue about a mile away from Tree of Life, and continued the service even as news of the shooting reached the community. The bentscher, or book containing the prayers said after meals, captured the moment perfectly, the man told Lidji: It featured the boy’s name and the starry Pittsburgh Steelers logo wrapped around the date, 10.27.18. Lidji eventually got hold of one of the bentschers.

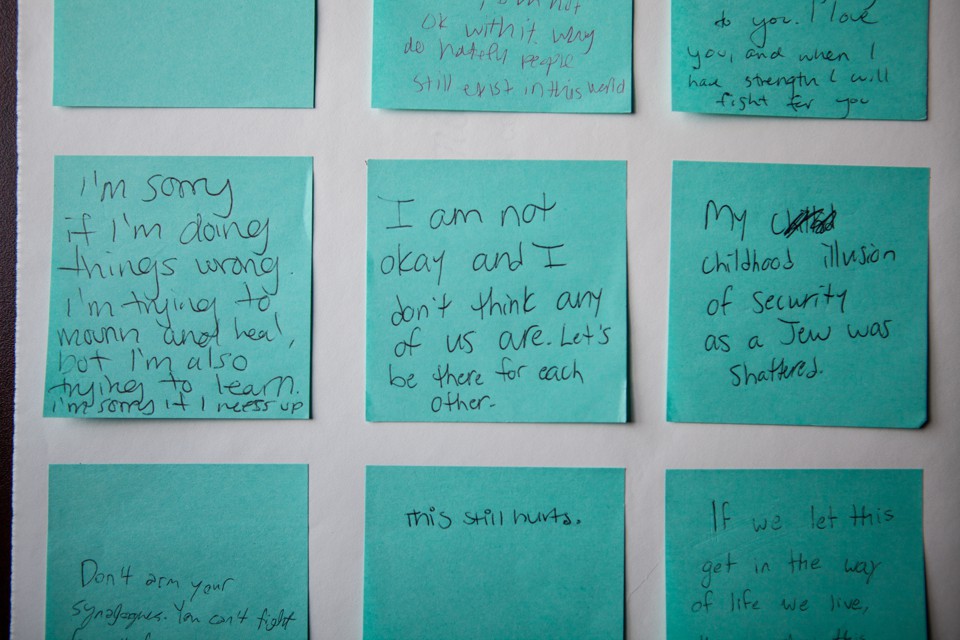

The most significant items Lidji has collected have what he calls “the shine,” a certain raw, emotional quality that indicates an object’s clear connection to the past. In the week after the attack, students at the Hillel Jewish University Center of Pittsburgh gathered and expressed their feelings on Post-its. “My childhood illusion of security as a Jew was shattered,” one student wrote. Lidji and his colleagues collected programs from memorial events, some more pointed than others: A community with a large Bhutanese population hosted a vigil, where attendees seemed to feel acutely the dangers of being an ethnic minority. A large Reform Jewish congregation, Rodef Shalom, hosted a small event where the preschool director reported that ever since the attack, the children had been obsessed with building elaborate protective structures out of blocks.

For whatever reason, people donated stacks upon stacks of I voted stickers from the November 6, 2018, election printed with the “Stronger than hate” logo designed to commemorate the attack. Lidji also collected bags of black paper strips, which protesters had torn, mimicking a Jewish funeral custom, during the Trump protest to symbolize their grief over the shooting and their dismay at the president’s arrival. Eighteen days after the shooting, the impromptu memorial that had covered the sidewalks, fences, and bushes around the Tree of Life synagogue finally came down; it took roughly a dozen people nine hours to take it apart. They laid everything out on paper, and a local business owner agreed to take the flowers for composting. Some of the volunteers, however, felt too pained to throw the stems away, so they made bundles to dry and preserve. Once summer arrived, the dried bouquets threatened to start decomposing in the business owner’s un-air-conditioned house, so he asked Lidji to come get them. Lidji now has crates of these flowers in his house.

A few weeks after the attack, Lidji got a call from a local family who wanted to donate a sign they made for the first memorial vigil, on the night of the shooting. When the mother brought her two children, 3 and 5, to the archives, the older child asked why they had to give the sign away. Sometimes, Lidji told her, things are so important that we have to make sure they will be around for a really long time. Right, the girl’s mom added. One day, you will be able to bring your grandchildren to see this sign.

[Read: The Jews of Pittsburgh bury their dead]

In late summer, Lidji picked up several vanloads’ worth of material from Jewish organizations around town, ranging from condolence notes to quilts to paper cranes they had received in the preceding months. Lidji said it will probably take him at least a year to go through it all. And there’s more: Tree of Life and the other two congregations that were in the building during the shooting received an estimated 10,000 letters in the days after the attack. It is unclear where they will end up.

“People will tell this story someday, and they’re going to tell it using this information that we’ve all left behind for them,” Lidji told me. “We’ve only done as good a job as we could do. We couldn’t save everything.”

The Heinz History Center is in a brick warehouse, the site of an old ice company in Pittsburgh’s Strip District, within sight of the Allegheny River. Named for Senator H. John Heinz III, the heir to the Heinz ketchup fortune, the center holds a variety of collections pertaining to western Pennsylvania, about such topics as the history of sports and the French and Indian War. The Rauh Jewish Archives—really just Lidji’s cubicle—sit on the sixth floor.

When I met Lidji there late last spring, he seemed exhausted. By now he really had two full-time jobs: Pittsburgh’s Jewish archivist, and archivist of the Tree of Life attack. The trove he is building will one day contain a large portion of the shooting’s physical imprint. Alone, these objects may seem insignificant, but together, they show the arc of this community’s grief: Poster-board signs made in solidarity, and in protest. Letters from around the world. Handicrafts and other offerings. A digital collection of community members’ posts and messages about the attack. Clips from local news outlets and Jewish media. Programs from events, the texts of speeches and sermons. Anything and everything that can be touched and seen, Lidji hopes to collect.

Dispositionally speaking, Lidji is geared much more toward pleasantly mundane local drama than toward grand narratives of history. He had been devising small-scale local-history projects long before he took up his formal post at the archives. Before last October, one of his projects at the archives was tracing the rivalry between two competing Yiddish-theater producers who had set up shop in Pittsburgh in the 1920s. He loved that the letters outlining their feuds were written in a spirit of high dudgeon, befitting their craft.

Lidji has had to figure out how to start telling the story of the Pittsburgh shooting, a story with much larger and darker implications than any he’s had to tell before. At first, it was Jewish organizations in and around Pittsburgh that approached him to help them make sense of the shooting—the Orthodox yeshiva where he went to high school, an area synagogue where one of the victims’ children attend services. Eventually, he started getting requests from people who live farther afield. In June, Lidji spoke at a convention in Colorado of mostly non-Orthodox chevrot kadisha, or sacred societies, made up of the members of Jewish communities who oversee the washing and burial of the dead. The convention was held not long after a gunman allegedly killed 51 people and wounded dozens more in a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, and also not long after a 19-year-old man allegedly opened fire in a synagogue in Poway, California, murdering one woman and injuring three others, including a rabbi and an 8-year-old girl.

Lidji began his talk with a story he sometimes tells when he’s trying to explain the deeper meaning of the archives project. Psalm 90 begins, “A prayer of Moses, the man of God.” According to Jewish tradition, most of the Psalms were composed by King David, who was born centuries after Moses died. How, Lidji asked, could David have known what Moses had said in his prayers?

In answer, Lidji offered his interpretation of a line from the Radak, a medieval Jewish commentator, painting a scene of dramatic discovery: King David, unable to sleep and wandering around his palace at night, finds a pottery jar containing a mysterious scroll bearing Moses’s prayers. How meaningful it must have been, Lidji said, for David to hold in his hands the words of the Jewish tradition’s greatest prophet. Psalm 90 itself describes how insignificant human events must seem to God: For in Your sight, a thousand years are like … a watch of the night. And yet the Jewish people, Lidji explained, have been able to maintain continuity in part because their archives have let them “come back later and be reminded.”

The bar mitzvah boy who persevered through his prayers even as his synagogue went on lockdown will one day die. The little girl who gave her sign to the archives will one day die. From dust to dust: A century hence, no one who witnessed the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting and its aftermath will be around to explain why they loved Squirrel Hill. If it survives, Lidji’s archive will be all that’s left to tell a more textured story. Depending on what comes next, those stones and signs and notes of grief could tell radically different stories: of a rare aberration in American Jewish history, or the restarting of an ancient clock.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community