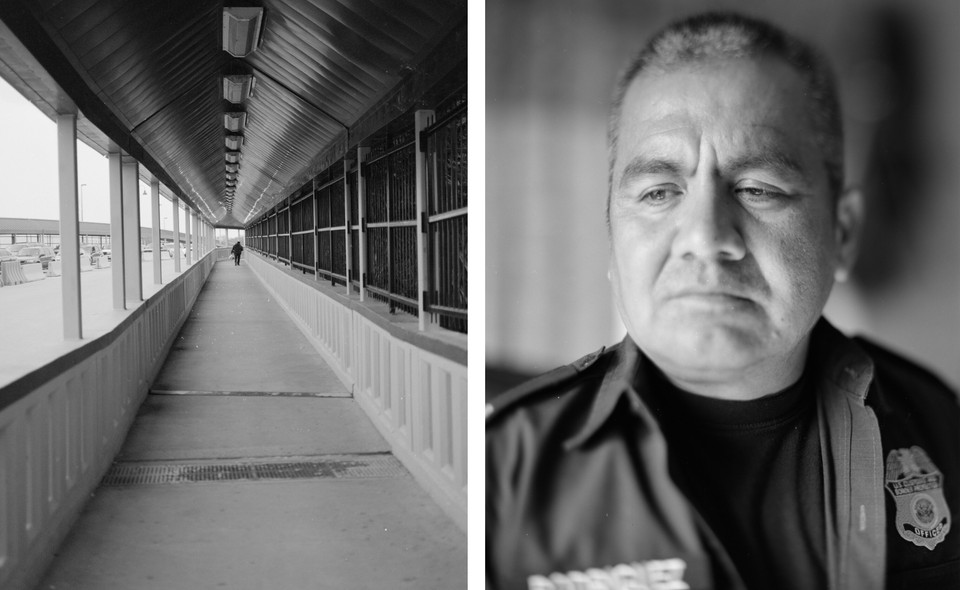

One afternoon in April 2018, Raul Rodriguez was working on his computer at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office in Los Indios, Texas, when two managers entered the building. Somebody must be in trouble, he thought. The managers usually arrived in pairs when they needed a witness.

For nearly two decades, Rodriguez had searched for people and drugs hidden in cargo waiting to get into the United States. He was proud of his work as a Customs and Border Protection officer; it gave him stability and a sense of purpose. Even in the spring of 2018, when public scrutiny of CBP began to intensify—the agency had officially started separating children from their parents—Rodriguez remained committed to his job. Though he wasn’t separating any families at the border, he’d canceled the visas and initiated the deportations of thousands of people in his years of service.

“Hey, Raulito,” one of the managers said, calling him over. Rodriguez walked past agents who were trying to look busy on their computers. Just two years from being eligible to retire, Rodriguez says he had an unblemished record. He couldn’t imagine what the managers wanted.

Rodriguez had been crossing bridges at the border since his parents, who were Mexican, had sent him to live with relatives in Texas when he was 5 years old. He’d wanted to stay in Mexico, but his mother insisted that he go: He was a United States citizen. She’d given birth to him just across the border in hopes that he would have a better life, and it was time for him to seize that opportunity. He started first grade at a public school in Mission, Texas. From then on, he saw his parents only on school breaks.

Read: Trump ends Obama-era protection for undocumented immigrants

As a child, he’d admired immigration agents’ crisp uniforms and air of authority. When he grew into a teenager, though, agents began to question him more aggressively, doubting his citizenship despite his Texas-issued birth certificate. He chalked it up to simple prejudice, no different from the white students at Sharyland High who provoked him to fistfights by calling him “wetback.” He decided he’d defy their stereotypes by one day becoming an agent himself. He would enforce the law, but without demeaning people as he did it.

Rodriguez joined the Navy in 1992. As a recruit, he cleaned floors and toilets, cooked, and drove a bus. Visiting his parents in Mexico, he wore his uniform. They didn’t say they were proud, but the looks on their faces made him feel as though growing up in Texas really had been worthwhile. And whenever he headed back across the border in uniform, he approached the agents on the bridge and thought: Now they’re going to have to accept me as an American.

But on that day in Los Indios in 2018, one of Rodriguez’s managers slid an envelope across the desk. Rodriguez remembers reading: “You are no longer a law-enforcement officer, pending further investigation.” His gun and badge were confiscated without explanation. He left the building in a stupor.

Days later, he sat down with investigators at a federal building in nearby McAllen, Texas. They told him his career in immigration and his military service before that—his identity as a veteran, an agent, and an American—were based on a lie. His United States citizenship was fraudulent. He was an undocumented immigrant himself.

Rodriguez joined the Immigration and Naturalization Service, a CBP predecessor agency, in 2000, after five years in the Navy. Soon after he graduated from training, Rodriguez’s parents hosted a cookout at their home, in the rural outskirts of Matamoros, Mexico. His wife chatted with his mom and sisters, while their two young children, Daira and Raul Jr., played with their cousins. Corridos played on the stereo and fajitas sizzled on the barbecue in front of the adobe house. Hurricanes had flattened similar structures nearby, but his family’s home still stood, because Rodriguez had refinished the walls with mud and grass every other year during school breaks.

His father, Margarito, had tutored Rodriguez in a strict vision of right and wrong. A farmer who wore a sweat-stained cowboy hat and a polyester shirt, Margarito kept big bags of cash at home earmarked for his agricultural co-op members’ hospital bills and funeral costs. He made sure Rodriguez understood that he never skimmed off the communal funds, though he could have gotten away with it. While other members bought new cars with stolen money, Margarito walked around town on foot asking for rides. “Always do the right thing, no matter what,” he told Rodriguez. Now Margarito advised him that, as an immigration agent, he must enforce the law no matter what—no exceptions, not even for family.

“You’re migra now,” one of Rodriguez’s cousins said during the barbecue. Immigration. As boys, he and Rodriguez had spent countless hours hunting rabbits and quail in the brush, gossiping like brothers about goings-on at the ranch. But the cousin had begun trafficking drugs and carrying a gun. “We’re on opposite ends,” Rodriguez recalled telling him. He cut ties with the cousin, and with close relatives who were living in the United States illegally.

Rodriguez began putting in long hours and overnight shifts, exacerbating tensions in his already rocky marriage. He and his wife eventually separated. His son, Raul Jr., who was 10 or 11 at the time, told me his father became an intermittent presence in his life as Rodriguez threw himself into his work.

By then, Rodriguez had already met his current wife, Anita, at the training academy they attended in Glynco, Georgia. During training, they’d found that they had a lot in common. Anita had grown up in Southern California, where immigration enforcement was a part of everyday life. As a kid, she would prank her undocumented cousins by yelling “La migra!” just to watch them run. Later, when Anita was 17, she became homeless and lived for a time in a car outside Yuma, Arizona, with an older sister and her sister’s five kids. Unauthorized immigrants making their way into the States ran over a footbridge near where they slept. Border Patrol officers noticed the homeless family and began bringing them food, water, and even Christmas presents. “Nobody was taking care of us except those Border Patrol agents,” Anita told me. “I wanted to be like them.” Her own father had moved to the United States from Mexico, and she wanted to help facilitate immigration. “The name of your company is Immigration and Naturalization Service,” she remembered an instructor at the academy saying. “I took that to heart.”

She moved from Arizona to South Texas, where Rodriguez was already stationed. After he separated from his wife, he and Anita married and had two kids of their own.

He was assigned to work one of the same bridges he’d crossed as a teen, and an agent who had given him a hard time back then became his colleague. His co-workers told him he looked like an undocumented immigrant, and they nicknamed him “la nutria,” after an invasive aquatic rodent that swims the Rio Grande—but now he was in on the joke. After long shifts, Rodriguez and his buddies would hang out together, drinking beer late into the night in the bridge parking lot.

Sometimes, he recognized employees of a Texas furniture factory, where he’d been a security guard, as they reentered the United States. One guy was so proud of Rodriguez for becoming an agent that he sought out his inspection lane just to see him in uniform. Rodriguez knew the man worked at the factory, in violation of the tourist visa he held. “Why did you have to come through my lane?” Rodriguez asked, before canceling his visa. He revoked about 10 workers’ papers this way.

Several years into his tenure with CBP, Rodriguez was buying cigarettes at a gas station near the bridge when a woman approached to ask if he would help her smuggle a child through his inspection lane. She wrote her phone number on a scrap of paper and pressed it into his hand. The proposition was brazen, but not uncommon—corruption was rampant within CBP. In the years after 9/11, officials had lowered hiring standards so that they could quickly bring in thousands of agents. Drug traffickers tried to infiltrate their ranks, Department of Homeland Security officials have said, and rogue agents seemed to flout the rules almost as often as they enforced them, accepting millions of dollars in bribes to allow drugs and undocumented immigrants to move into the U.S. undetected. (CBP did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesperson confirmed to the Los Angeles Times that Rodriguez had been employed by the agency but declined any further comment.)

Read: The Border Patrol’s corruption problem

Rodriguez called the woman’s phone number and set up a meeting. He agreed to accept a bribe of $300. The woman and child entered the United States through his inspection lane and were arrested immediately—Rodriguez had worn a wire and taped the encounter.

For his role in the operation, CBP flew Rodriguez to Washington in 2007 to accept the agency’s national award for integrity. “Nothing is more critical to CBP’s mission,” then-Commissioner W. Ralph Basham said at the ceremony. In a flat-brimmed hat and white gloves, Rodriguez walked across the stage to shake Basham’s hand.

Anita told me that when people of Mexican heritage become agents, their family members tend to be ambivalent. “On one hand they’re very proud of us, because to work for the government—that’s a lofty thing in Mexico,” Anita said. “But then on the other hand, traicionero—you’re a traitor, because you’re deporting your own people.” Rodriguez says he never let that stop him: Too much empathy could lead an agent to bend the rules. But some cases did haunt him.

In his early years as an officer, an English-speaking teenager walked up to him on the bridge from the Mexican side. Quiet and alert, the kid was not unlike Rodriguez had been at that age, except for his lack of papers. He admitted that he’d been living illegally in the U.S. most of his life; he needed to return to continue high school. Rodriguez asked why he had risked a trip to Mexico if he knew he wouldn’t be allowed back into the U.S. The boy explained that his grandmother had died and he’d gone to pay his respects before she was buried. “I wanted to see her one last time,” he said. Rodriguez told him his best hope for returning was to one day marry a U.S. citizen. But for now, Rodriguez had little doubt about the rules. He sent the teen back to Mexico.

That night, the boy attempted to swim across the Rio Grande. Agents found his body floating beneath the bridge the next morning.

In the twilight of the Obama administration, Central American children and families began arriving at the border in droves, seeking protection from poverty and gang violence, and reunion with family in the U.S. Rodriguez, by then a veteran CBP officer, believed that many asylum seekers had been coached to tell the same sad stories so that they would be released into the United States to await their day in court. The then–presidential candidate Donald Trump promised to lock these people up. Rodriguez voted for Trump. The Rio Grande Valley soon became the epicenter of CBP’s effort to deter migrant families by removing thousands of children from their parents.

Any parent could see the separations were inhumane, Rodriguez told me. Someone in Washington had taken the crackdown too far. But what could he do, as a nobody on the bridge? He told trainee officers, “Leave your heart at home.” He focused on his sense of duty and followed orders.

As the uproar over family separations engulfed the Trump administration, Rodriguez sat before a pair of investigators in a dim room with a one-way mirror, facing a crisis of his own. They showed him a document filled out in longhand with his and his parents’ names. The header read acta de nacimiento—a certificate of birth, issued in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. It was evidence, they said, that Rodriguez had been born in Mexico, not the United States. “Do you recognize this?”

Rodriguez was incredulous. He wrote in a handwritten statement that morning, “I have always believed I was a United States Citizen and still believe I’m a United States Citizen.” His mother had died in 2013, so his father was the one living witness who could clear things up. Rodriguez offered to arrange for investigators to meet with Margarito later that day. He called a nephew and told him to get his father from Mexico to the meeting spot—a Starbucks near the border—even if he had to drag him there. A few hours later, Margarito arrived to speak with Rodriguez and the investigators.

Margarito was evasive when officials first showed him the acta. “I need to know the truth,” Rodriguez told him. “Tell me the truth.” Margarito looked down at the table. Rodriguez had been born at the adobe house outside Matamoros. He explained that about two months later, one of his sisters had arranged for a midwife to register a false birth certificate.

The fraudulent document had come to light because Rodriguez had petitioned for one of his brothers in Mexico to get a green card. An officer with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency that issues green cards, flagged the petition because Rodriguez’s Texas-issued birth certificate had been registered by a midwife who was later convicted of fraud. (According to The Washington Post, government officials have said that cases against midwives during the 1990s uncovered roughly 15,000 falsely registered babies born in Mexico.) Rodriguez now had no legal status in the country, and was fired from Customs and Border Protection for failing to meet a basic condition of employment: U.S. citizenship.

Margarito stressed to investigators that he’d always hidden the truth from his son. (When Homeland Security finished its investigation into Rodriguez, a prosecutor from the U.S. attorney’s office in McAllen declined to charge him with any crimes.) A few hours later, still stunned by his father’s confession, Rodriguez placed an urgent call to his own son from his first marriage, Raul Rodriguez Jr.

Raul Jr. was inspecting a home for insect and rodent infestations when he received his father’s call. At 27, he was working at a pest-control company in hopes of moving his three young kids out of an apartment in Los Fresnos, Texas, and had just landed an interview for a job with U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

He went to his father’s house, where he found his father and his stepmother, Anita, looking ashen. They had set out a chair for him. He thought his father might have a serious illness. Rodriguez began to tell Raul Jr. about the midwife, the acta, and Margarito’s confession. Raul Jr.’s disbelief gave way to panic when his father explained that he, too, would likely lose his citizenship.

In 1990, Rodriguez’s first wife, who was a Mexican citizen, gave birth to Raul Jr. in Matamoros. Though he was born in Mexico, he was American by birth because of his father’s nationality. Raul Jr. later obtained a certificate to prove his “acquired citizenship.” But those papers were based on a fraud. “I don’t even know how to describe myself,” Raul Jr. told me. “I don’t know if I’m an illegal or not.” In order to avoid making a false claim to U.S. citizenship—which could have barred him from the country—Raul Jr. returned his certificate of citizenship to the government. He put his application to CBP, and a new house, on hold indefinitely. He applied for a green card through his wife.

While he waits, he, like his father, is at risk of deportation.

Along with more than 100,000 undocumented immigrants in the Rio Grande Valley, Rodriguez and his son are geographically hemmed in. To the south is the U.S.-Mexico border, a deep-green river surveilled by thousands of federal agents and by blimps repurposed from Iraqi and Afghan battlefields. To the east is the Gulf of Mexico, where boaters are subject to immigration checks by the Coast Guard. Border Patrol checkpoints dot the major roads heading north out of the valley. Every driver must stop and answer the question: Are you a U.S. citizen?

An agent from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which handles deportations, set up a meeting with Rodriguez a few months after the fraudulent birth certificate was discovered. The agent said he wanted to help him by going over the details of his case. But Rodriguez, who knew the agent from work, sensed that this was a ploy to get more information out of him. He took it as a warning from ICE: We’re watching.

More than 50,000 officers patrol the border and the interior of the country, according to the nonprofit American Immigration Council. They’re easy to spot at Rodriguez’s kids’ high school. Former colleagues who noticed Rodriguez’s absence but were not privy to the details of his case figured that he’d been fired for corruption. He’s always been “chueco,” a retired agent named John Garcia told me he overheard someone say at work. Crooked. Just as Rodriguez had once cut ties with his undocumented family members, agents began to avoid eye contact when they saw him in public, at restaurants or the grocery store. “They treat him like he’s a pariah,” Anita told me.

Rodriguez’s integrity award sits above the TV where he watches the local news every morning from the treadmill. He spends the rest of the day tending to his sheep, cows, and chickens, rarely leaving his property, because a traffic stop could ultimately lead to deportation. “I don’t have any legal status in the U.S.,” he told me. “I’m deportable.”

Rodriguez and Anita have refinanced their house and raided the kids’ college fund to supplement Anita’s income from her job at the Department of Homeland Security. Fired just shy of retirement, Rodriguez lost his eligibility to receive a $4,400-a-month pension along with his citizenship. Rodriguez feared that the stress of his new reality could lead to divorce.

Last fall, as the evening cooled to 90 degrees, he drove to his teenage son’s football game, careful to use blinkers at every turn. At the game, the band played the national anthem before kickoff, and an announcer asked veterans to rise and be recognized. Rodriguez remained seated. Anita, adamant that his service still counted for something, nudged him in the ribs. “Stand up.”

Soon after he was fired, Rodriguez got a large CBP badge tattooed on his left shoulder. A Mexican flag splits the badge into two halves.

He applied to become a lawful permanent resident as the spouse of a U.S. citizen, and was forthright in his interview. Yes, he told the official, he had made a false claim to U.S. citizenship, but only because he hadn’t known the truth. Yes, he had voted in a federal election as an undocumented immigrant. He expected no special treatment, just the pension, health benefits, and safety from deportation he felt he’d earned through his nearly two decades at CBP. With some patience, he was confident that he could get his status sorted out. By last fall, he had been waiting for a response for almost a year and a half.

Rodriguez says he can now see the impacts of immigration enforcement that he once preferred to leave unexamined. “I can relate to people who I turned back, people that I deported,” he said. “They call it karma.”

Still, he doesn’t regret his service, and distinguishes himself from other unauthorized immigrants. “There are a lot of people trying to do it the easier way,” he told me. “I just found out, and I’m trying to do it correctly.”

If deported, he would live on family property in Tamaulipas. The State Department’s “Do not travel” warning to U.S. citizens says of the area: “Murder, armed robbery, carjacking, kidnapping, extortion, and sexual assault [are] common along the northern border.” As an agent, Rodriguez had put traffickers in jail, and his face is widely recognizable from his years on the bridge. “I don’t know how long I can survive,” he told me.

Read: An astonishing government report on conditions at the border

Despite those risks, Rodriguez dismissed the idea that he should apply for asylum—a legal pathway to U.S. residence that the Trump administration has sought to eradicate, claiming it is rife with fraud. “I’m not going to do it that way. I’d rather get deported,” Rodriguez said. “I’m going to practice what I preach.”

Once passionate about her work, Anita told me she has “lost faith in the system.” But without a college education, she sees no other option. Her job in immigration, she said, “is what’s feeding my family.” Rodriguez “lives by the rules … and even now he says that if the government chooses to deport him, he’s going to go,” Anita said, her voice catching. He would turn himself in before he would hide from ICE. “I can’t let that happen. What am I going to do? What are my kids going to do? What is he going to do over there? He’s a federal officer.” Anita researches Rodriguez’s case most nights and keeps a close watch on other military veterans in the news facing deportation.

In October, Rodriguez received a letter from Citizenship and Immigration Services. His green-card application had been denied because he had falsely claimed to be an American citizen and illegally voted. The letter argued that Rodriguez did not qualify for leniency, even if he did not know about his status at the time. (USCIS declined to comment on specific cases.)

In our interviews, Rodriguez said he understood that the government had to apply the rules to him the way it did to everyone else—his undocumented relatives, his former co-workers, and the boy who drowned under the bridge. But he drew a distinction between how he’d carried out his duties and how officials were handling his case. “I wasn’t being strict; I was just abiding by what the law says,” he told me. “And these people are not doing what the law says.” He believed that he still qualified for an exemption provided by the law for those who make a false claim to U.S. citizenship unwittingly. But in its denial letter, USCIS said it could not make an exception for Rodriguez even if he was unaware of his status at the time, citing recent precedent. Still, Rodriguez held out hope that he could convince the agency to reverse its decision. Immigration lawyers told me, however, that federal officials are granting fewer exceptions across the board. “Apply the right laws, and apply the right rules,” Rodriguez told me. He believed the agency was singling him out unfairly. “Treat me the same—that’s all I want.” His problem might be that it already is.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community