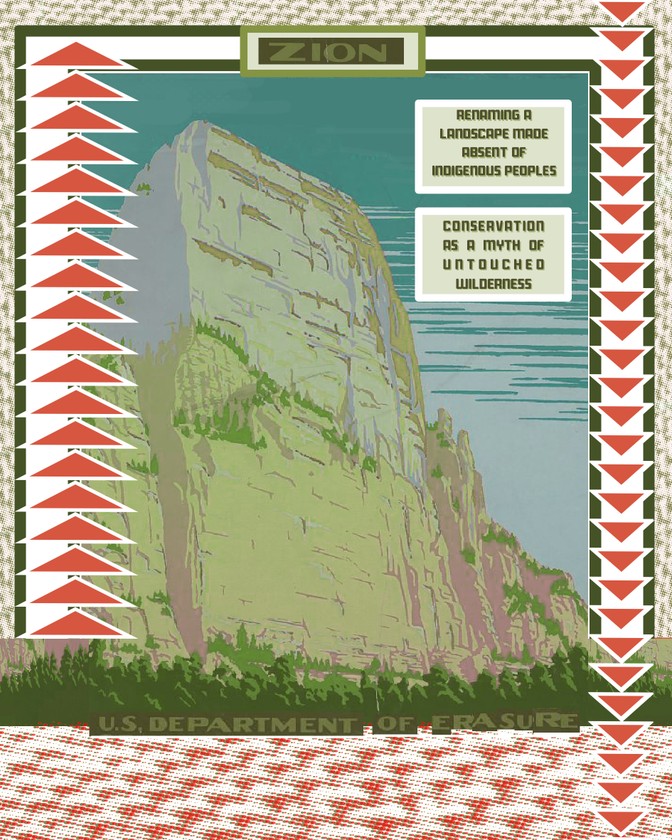

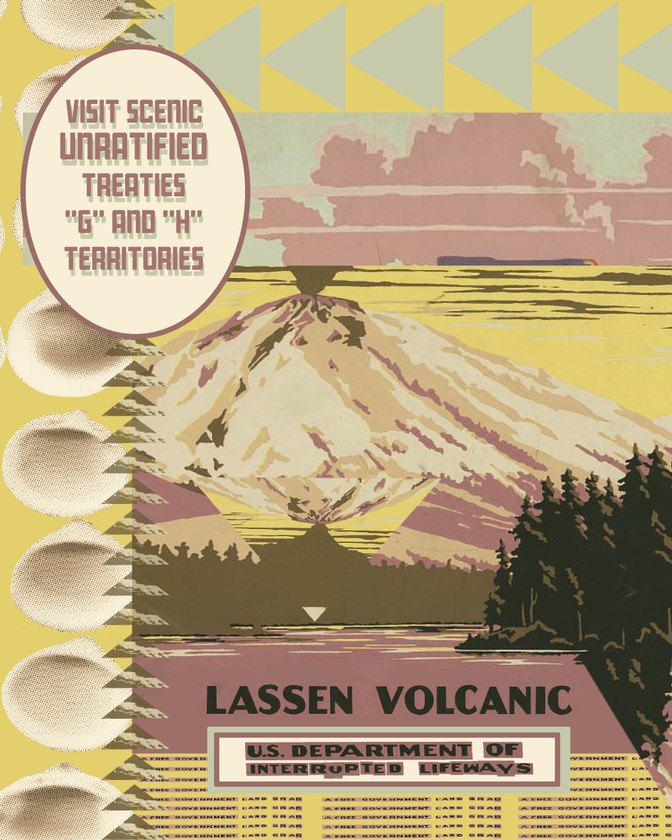

Illustrations by Sarah Biscarra Dilley

This article is part of a new series called “Who Owns America’s Wilderness?”

America’s first national park is only 15 years younger than The Atlantic, and at this magazine we have long told ourselves that our histories are intertwined. That John Muir made his late-19th-century case for the national parks in our pages is part of institutional lore. We are not alone in our warm feelings toward the parks. Many, if not most, Americans experience an uncomplicated pride standing on the Grand Canyon’s edge, or in the cool shade of an old-growth sequoia grove. At a moment when so much of our nation’s history has come under scrutiny, the park system, and the reverence for nature that led to its creation, rank among our loftiest achievements.

The parks owe their existence to a remarkable turnabout in American sentiment. The first Europeans to reach North America’s shores regarded its interior wild spaces as wastelands. Viewed from Plymouth Rock, the American wilderness was a pagan realm to be tamed and brought to order by a westward wave of white settlers who ripped minerals out of mountains, blackened rivers, and mowed down forests with frightening speed. Even the mighty coast redwoods barely survived this assault: 95 percent of them have been logged since Europeans first settled in California. America’s dominant culture cast its eyes upon these trees—the world’s tallest, alive for centuries—and saw raw material for the market.

Muir helped Americans to reimagine the wild as a sacred space. A wild-bearded

preacher’s son who was happy to affect the role of the sage, Muir took inspiration from the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of The Atlantic’s founders. He conceived of the American continent as a new Eden, a favored garden “rolled and sifted in seas with infinite loving deliberation … pressed and crumpled into folds and ridges.” These mountain ridges had called to him, beckoning him up to their highest reaches.

Muir returned from his wanderings bearing a spiritual message for “tired, nerve-shaken, and over-civilized” readers. He had found salvation in nature. Gazing down into the Grand Canyon, he saw the “grandest of God’s terrestrial cities,” its stone walls “adorned with richly fretted cornice and battlement spire and tower,” its color “unearthly … as if you had found it after death, on some other star.”

He urged readers to set forth on their own pilgrimages, to landscapes that lay beyond the “clearing, trampling work of civilization.” If one visited these spectacular places and paid attention to the right details—the play of light on granite, fragrant pines trembling in the wind—one could experience divine nature. One could see its processes “whirling and flowing, allowing no rest but in rhythmical motion, chasing everything in endless song out of one beautiful form into another.” One could be changed, profoundly, by the encounter.

Michelle Nijhuis: Don’t cancel John Muir

Muir observed his Eden closely, and could see that it was beginning to fall. It is now obvious that human activity is unwinding complex ecologies that required millions of years of nature’s patient creativity for their formation. In the late 19th century, Muir could already see the shrinking of our continent’s glaciers, the thinning of its herds, the stresses on its woodlands. He knew our wildernesses needed protection, especially if they were to forever perform their sacred function as backdrops to transcendent human experience.

Muir ranks among the most influential writer-activists in American history, in part because he did not make his arguments in a dry, academic manner. He wove into his prose some of the finest nature poems ever written in English. Like many parents, I have read Muir to my children at their bedsides, hoping that his words would awaken in them new sensitivities, so that they too might one day trek into California’s high mountains and find a “range of light.”

Muir’s mythopoeic vision of the wilderness proved so seductive that it is hard to believe it was once radical. In the 12 decades since he wrote his stirring essays for The Atlantic, the United States has inaugurated 60 national parks, encompassing tens of millions of acres. The idea of a national park has proved even more successful, inspiring copycats across the planet.

For these achievements, Muir deserves his due, and he has received it: Until quite recently, he was regarded as something of a secular saint. At The Atlantic, we have decided to pay him the only kind of tribute that is proper for a magazine of ideas, by taking on his ideas in earnest. For however majestic Muir’s account of nature, and whatever his conservation victories, his vision of the wilderness was limited. His is not the last or best word on the subject. This spring season, while many of us are preparing to emerge from our most indoor year, The Atlantic is launching a special series—“Who Owns America’s Wilderness?”—that will try to help Americans see their wildlands anew.

We begin with a reckoning. Like other nature writers of his time, Muir conceived of wilderness as a realm set apart from the human world. A fine sentiment, except that Muir’s most beloved peaks, canyons, and forests were empty because they’d been depopulated by force within his own living memory. Muir was an exceptionally curious man. On his hikes, he pushed his mind thousands of years into the past, and dwelled upon the mysteries of every last sunlit pinecone. But the human dramas that unfolded in these wild spaces held no interest for him. In the sweeping story Muir told about the landscapes that became national parks, America’s original inhabitants did not earn pride of place, or really any place. This series launches with our May cover story, “Return the National Parks to the Tribes,” by the writer David Treuer, who is Native American. It will give readers a full view of the parks’ past, and a compelling vision of their potential future.

David Treuer: Return the national parks to the tribes

Another essay in our launch package, by Michelle Nijhuis, confronts Muir’s legacy directly, but without presenting a false choice between deification and cancellation. Another, by Emma Marris, takes on the distortions of high-tech nature documentaries, which are more popular than ever and may now be the primary lens through which people experience wilderness.

In the months to come, our writers will consider the more distant past and future of the American wild. We will try to imagine the first human experience of the North American wilderness, more than 15,000 years ago. We’ll imagine how wilderness areas might grow, with wildlife corridors that transcend national borders, connecting a continent-spanning network of mega-parks, perhaps as expansive as E. O. Wilson’s “Half-Earth” proposal. We’ll visit China’s new national parks, and speculate about the first wilderness reserves in space.

But first, we turn our attention to America’s brief history. Midway through Treuer’s reconsideration of the national parks, he makes an instructive point about the evolution of American feeling toward the wild. For even as Americans were violently removing Native peoples from the park landscapes, our beliefs about the rivers, the trees, and the snowy ranges were changing, becoming more resonant with views held by manifest destiny’s victims, peoples who had lived on these lands for 600 generations, at least.

“Americans have gradually assimilated to our cultures, our worldview, and our modes of connecting to nature,” Treuer writes. “America has succeeded in becoming more Indian over the past 245 years rather than the other way around.” John Muir gave Americans a new sacred story about the wild. His story did not recognize the humanity of America’s Indigenous peoples, or the meaning of their long tenure on this portion of the Earth. And yet, it was in some ways remarkably Indigenous in spirit. With this series, we make notes toward a new synthesis, a more expansive story about the American wild and all those who have called it home.

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

/media/img/posts/2021/04/wilderness_test_1/original.png)