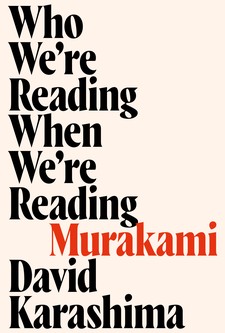

How Murakami, whose book sales today number in the millions, and whose name is recognized even by those who have never read his work, came to be the figurehead of Japanese literature abroad is the subject of Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami, a slim but fascinating new treatise by David Karashima on the business of bringing the best-selling novelist to a global audience.

The cover of the book’s Japanese edition hints that Murakami the man and Murakami the writer in translation might not be identical. The title is splayed across the top in Japanese characters, except for Murakami’s name, which is written in roman letters: The juxtaposition, not present in the English-language edition, implies a cultural product. When a person buys Murakami’s books in English, they are receiving both author and publishing machine. Novelists may not be iPhones but, when producing a blockbuster novel, the American market plays a role. And Karashima focuses on how Murakami was launched into that very market—as he puts it, “the stories of the colorful cast of characters who first contributed to publishing Murakami’s work in English.” Along the way, he investigates the motives of those characters, the qualities they celebrated, and the words they sliced away.

Karashima leads his readers on a tour of translational tinkering. He begins with Birnbaum, Murakami’s first translator, and Elmer Luke, the editor at Kodansha, a Japanese publisher that was looking to break into the American market. An Adventure Surrounding Sheep, Murakami’s third novel, is a surreal mystery that begins when the protagonist learns of the death of a girl he used to sleep with. The original story was set in the ’70s, but Birnbaum and Luke, the book’s editor, had “American—particularly New York American—readers in mind,” and believed they wanted something “contemporary.” So for the book’s 1989 publication in the United States, they took out obvious references to the time period. They also added a slight nod to a Ronald Reagan speech that was made after the time period of the book, and changed the title to A Wild Sheep Chase. (Birnbaum is reported to have said, “Don’t you think it’s a much better title than the original?”)

From their next project, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, they trimmed about 100 pages. Although Murakami said that he wanted to write the book to include some “illogical” sections, Birnbaum and Luke feared that American readers would lose interest and made significant cuts. In particular, they removed passages including a character called the Girl in Pink, who leads the protagonist through a maze. For example, the original contained four pages of her singing about her pink bicycle. Hosea Hirata, an associate professor of Japanese at Tufts University, believes this had the effect of censoring the original, explaining to Karashima that several omitted sections show the Girl in Pink being sexually aggressive. He gives examples of the girl and the protagonist’s cut conversations. Two in particular that stand out are:

“Hey,” the girl called me, putting down the book. “You sure you don’t want me to swallow your semen?”

and

“I got a hard-on.”

“Let me see,” said the girl. I hesitated a bit, but decided that I would let her see it. I was too tired to keep arguing about it. And after all I won’t be in the world for too long. I didn’t think that by showing my healthy erect penis to a seventeen-year girl, it would develop into a grave social problem.

“I see …” said the girl looking at my erect penis. “Can I touch it?”

When asked about these cuts, Luke responds that his problem with these scenes was not their sexuality but that they were “preposterous almost” and that he didn’t want “the author or the book to be dismissed.” He doesn’t think her age would have been an issue, saying, “It would have been different if she was twelve or something.” Neither Luke nor Karashima delves further into why the girl’s sexuality might or might not be preposterous, or lead to the book being dismissed by American audiences. Karashima quotes the critic Gitte Marianne Hansen, who noted that it was a “shame” that these sections were not preserved, because she believes “that sex descriptions in the Murakami world have a lot to do with self-discovery and communication between characters who don’t understand each other, rather than sex in the pornographic sense. And that feeling might be lost when these explicit words and images are removed.”

Source link

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community

Black America Breaking News for the African American Community